Collectors

A Collectors Mind

- Sir Alan Barlow (1881-1968) - President of the Oriental Ceramic Society 1936If the private collector is accused of being a selfish and acquisitive parasite, addicted to envy, malice, and uncharitableness, the credulous victim of changing fashions or false standards, his reply must broadly be that he is helping in the accumulation and diffusion of knowledge and taste.

In my career I have been lucky enough to meet and become friends with collectors who are as passionate about ceramics as I am. Many of these collectors have build up an impressive collections which created a legacy of knowledge. Their collections and scholarly knowledge have brought new understanding about the subject.

In this article I would like to address some of the collectors I dealt with over the years and who I admired greatly.

John Drew

John Drew was born in 1933 in Tideswell, Derbyshire, where his father was curate. The family moved to Norfolk whilst he was still a baby and his father became the rector of the parish of Intwood and Keswick. He was educated at Sedbergh School and after National Service in the R.A.F. being taught Russian, he went to Queens College, Oxford to read Greats (Classics). He spent nearly all his working life in various African countries as an archivist, moving to a post at Cape Town University in 1978. He remained in Cape Town after his retirement until his death in 2006. He had a great love of the English countryside (but not the climate) and this is shown in many of the pieces he collected.

His taste was varied and ranged from Neolithic right through to the 18th Century. When we sent photographs to his home in Cape Town of pieces we thought he might be interested in, he would write long funny well observed letters back, wanting to add many of the items to his growing collection. Over the years we got to know him better and better, and during the last few years it was very rare for him to not want all the pieces we offered him. We knew his taste, even though his taste was so varied. This was in no small part because he had a very good eye and it was a pleasure finding things that interested him, because they were also very interesting to us.

He never got to put his collection on display, something he hoped to do while on retirement in England. So it was with a mixture of pleasure and sadness that we offered these pieces from his collection in an exhibition in London. Most pieces have a John Drew collection label, so when the collection was split up there will be some lasting record of the love and hard work he put into his two decades of collecting.

SOLD

Condition

The top rim, and toe of the boot with numerous filled chips, small glaze losses filled.

Size

Height : 9.6 cm (4 inches).

Provenance

R & G McPherson Antiques, stock number 16338. The John Drew Collection of Chinese and Japanese Ceramics, collection number 429.

Stock number

23335

- Werner Muensterberger (1913-2011) - Psychoanalist‘A connoisseur may cherish or admire an object, but receives little emotional support from its ownership’; ‘there is no affective attachment to the object’; ‘he does not need to own the object and can live without it’; ‘the committed collector, on the other hand, cannot.’

Sir Michael Butler

Michael Butler was born at Blandford, Dorset, on February 27 1927. He became a diplomate working for the Thatcher administration in Brussels, working long hours.

Beside his job he became highly interested in the subject of 17th century porcelain. His first item was inspired by his friend Nicholas Thompsom in the 1960’s, who suggested he should fill his empty shells with objects like he did. So he went to Sotheby’s auction and found a box with in it Bamboo shaped, apple green wine pot, among 5 other objects. It had cost him 15 GBP. He wasn’t sure what it was and started to ask his friends if they knew, but soon realized there was not allot of knowledge about this time in the Chinese ceramic history. When the imperial factories were closed and the painters and potters went into the private market.

Michael Butler started to learn about the subject and became a leading collector of 17th century Chinese porcelain. By studying the different sorts of porcelain and collecting them from all over the world he became a leading expert respected in China itself.

He wrote several books, traveled around the work and created a museum next to house to show and share his collection in full.

He died in 2014 aged 86 leaving behind a collection of 600 pieces.

- Sir Michael ButlerIt's only by having a great many pieces, that one can in fact date them properly

Nicholas de la Mare Thompson

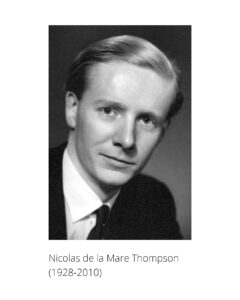

Nicholas de la Mare Thompson (1928-2010)

Nicholas de la Mare Thompson, the grandson of the author Walter de la Mare spent his career in publishing. He started at Nesbit where he was editor of the Janet and John series of children’s books but not all of his career was so safe. He wrestled with W.H. Smith over the content of Madonna’s raunchy Sex book on behalf of Paul Hamlyn’s Octopus Group and defeated Margaret Thatcher over Spycatcher. He could not bare dogma or hypocrisy.

It was hardly surprising that as a committee member of the O.C.S. he had his own ideas. He read and could recite great swaths of the articles of the Society, he used this not to attack but to stimulate debate. He approached the Society in the same way as he approached his understanding of Chinese ceramics, by stripping it down and starting again using clear empirical thinking. He was very concerned the Society was open to all and was run for the benefit of all members.

Nicholas came from a family of collectors, his love of oriental ceramics was broad but his focus was on early monochromes, especially those from the Song dynasty. He bought what he loved, what he thought had merit, not what was said to be good, and certainly not anything because it was fashionable. He didn’t have a stamp collectors’ approach, filling in the gaps of pre-existing ordered collection, rather he would react to an object, feeling it was right for his collection. Sometimes he wasn’t sure if it was right for his collection or not. He would then “borrow” pieces and live with them, other times he would ask his wife Caroline, who’s eye he trusted, if he should keep the piece or not. He was amused because I was often able to know if he would keep a piece before he did. We discussed “pots” endlessly, he loved to talk about ceramics with a wide variety of people and enjoyed the company of others on O.C.S. trips as well as in discussion groups or anywhere else. Later on he combined his love of Chinese ceramics with his love of books by extending his library to include rare early books, he used these to trace the development of collecting and scholarship in the 19th and early 20th century. He was fascinated by earlier scholarship, what was not understood but also what they understood, and we have lost. He was always reading and wanted to know more right up to the end, he didn’t see impending death as a barrier to knowledge or indeed collecting. The week before he died he questioned, if only for a second, whether it was too late to buy another pot for the collection. He concluded it was not, he was a true collector.

Nicolas died on the 25th of April 2010 at the age of 82 after living with cancer for two years. He leaves behind his energetically supportive wife Caroline and his three children. He was a kind, gentle and incredibly civilised man with a very sharp mind and dry sense of humour, he was passionate about the Society, its aims and its members. He was an incredibly supportive and thoughtful friend and will be missed very much.

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

SOLD

Condition

A bruise to the rim from a crack along the rim and a very small rim crack, see photographs below..

Size

Diameter 12 cm (4 3/4 inches)

Provenance

Knapton and Rasti Asian Art. Robert McPherson Antiques, Nicholas de la Mare Thompson (1928-2010) purchased 25th of April 2005.

Stock number

26671.