D.R. Laurence MD on collecting Chinese Porcelain

CHINESE PORCELAIN 25 YEARS OF UNSCHOLARY COLLECTING

- R.L. Hobson, British Museum, 1915The antiquity of Chinese porcelain, its variety and beauty, and the wonderful skill of the Chinese craftsmen, accumulated from the traditions of centuries, have made the study of the potter’s art in China peculiarly absorbing and attractive

An Entertainment and an Anthology of Scholars’ Taste by D.R Laurence MD, 2003

Queen Mary II (1662-1694) “amused herself by forming a vast collection of hideous images…grotesque baubles. [Satirists repeated] that a fine lady valued her [Chinese ceramics] quite as much as she valued her monkey and much more than she valued her husband’’ (T.B. Macaulay, History of England, 1855)

Copyright, text and selection D.R. Laurence The author’s moral rights have been asserted. Copyright, text and selection D.R. Laurence The author’s moral rights have been asserted.

- Acknowledgements

- introduction

- Autobiography

- Psychology of collecting

- Dealers and Experts

- Gaining Knowledge

- An Art or a Craft

- Collector, Connoisseur, Dealer, Provenance, Fakes

- The Anthology By Author

- Collectors

- The Aesthetics of repaired porcelain

- A vision from People of craftmanship and scholarly knowledge

- References

Acknowledgements

To my friends for encouraging my learning over many years. To Tessa Milne for producing this work from my handwriting. To Roy Davids for reading and contributing to the text. To the following sources: Faber and Faber; Random House; Art Services International; Orientations Magazine; Pearson Education; Princeton University Press; Southeast Asian Ceramic Society; Collections Baur; Burlington Magazine; Souvenir Press; Thames and Hudson; Oxford University Press; Oriental Ceramic Society; Victoria and Albert Museum; Bamboo Publishing; De Tijdstroom b.v. Lochem; Reaktion Books; Wenwu; A & C Black Orion Publishing Group; Leisure and Cultural Services Department, HK; Chrysalis Books; Philip Rawson. (Note: some of the above are not the original publishers of quoted material.)

The Oriental Ceramic Society tells me that it will be pleased if you contact it with a view to membership, at 30B Torrington Square, London WC1E 7JL

(email: ocs-london@beeb.net).

It holds meetings, arranges trips and publishes Transactions.

A diversion on the trials of obtaining permission to quote copyright material

As a person who recognises that ‘intellectual property’ is, in general, a ‘good thing’, I determined to abide by its rules. This has proved to be no easy task. Ask anyone who has any pretension to know about copyright and you will get advice; but each person’s advice is different. Though tempted, I shut my ears to the Siren song of those who said that what I was doing came under the ‘exemption’ rule as ‘fair dealing’ (for criticism or review), and I need not seek any permission. Tracing current copyright holders is a test of both skill and patience. I therefore follow the authoritative advice of the Writers’ and Artists’ Year Book 2003 (A & C Black), ‘the no. 1 bestseller: a must for established and aspiring writers’ (Society of Authors). It states: ‘half a dozen words may usually [emphasis added] be used without permission…If you do not get a reply when you ask for permission to quote, insert a notice in your work saying that you have tried without success to contact the copyright owner, and would be pleased to hear from him or her so that the matter could be cleared up – and keep a copy of all relevant correspondence, in order to back up your claim of having tried to get in touch.’ This I now optimistically do. DRL

Published by D.R. Laurence, 37 Denning Road, London NW3 1ST (UK)

INTRODUCTION

This text is an unscholarly distraction or entertainment and a sort of tribute to the genius of China that has given me pleasure and diversion for more than 25 years.

‘To speak of porcelain is to think of China, for not only were our European porcelains made in rivalry with the wonderful ware brought from that country, but every connoisseur and every unprejudiced potter will admit, in his lucid moments, that the porcelain of the Chinese marks the very crowning point of the potter’s achievements’ (William Burton, 1906).

The pleasures of amateur collectors would be much restricted were it not for the serious scholarship of others, and it is largely as a tribute to scholars’ insights that this slender assemblage has been made. The making of it has pleased me, and maybe it may amuse some fellow collectors.

- D.R. LaurenceI realised instead that what I needed to do was to educate my taste, and to decide what reliably gave me renewed pleasure every time I looked at it. And I also recognised truth in some of the various deeper analyses of the psychology of collecting.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

I first became conscious of oriental ceramics in 1946-47 whilst serving in Japan as a medical specialist in the Royal New Zealand Army Medical Corps, component of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF). I was stationed at a military hospital on the shore of the Inland Sea between Yamaguchi and Shimonoseki. Opportunities for seeing and acquiring local arts were limited chiefly to periods of leave in Japan. However I did purchase a few ceramic pieces using the informal currency of the time (army cigarettes and warm woollen Australian army-issue underwear; both in demand by the local population).

On returning to London I took a bowl, that I now know to have been wucai, to a Mayfair oriental dealer and naively requested the elegant young man who approached to tell me what it was. He took it in his hand, gave it a brief glance and, returning it, murmured, ‘Not the period, Sir, I am afraid.’ It was only after I found myself on the pavement outside that I realised that I had no notion of what might be ‘the period’ that my bowl was not of.

Thirty years passed on other concerns that seemed to require undivided attention. Although during that period I made various tentative excursions into collecting: oriental carpets, etchings, bronzes, posters, a mounted head of a warthog, stuffed birds and fish, a Pratt’s petrol can and other ‘bygones’.

My interest in ceramics revived in the 1970’s when I bought some early nineteenth-century English transfer-printed earthenware cheaply to decorate a blank wall. This it achieved successfully, and the damaged condition of the plates did not obtrude when they were hung closely massed. I also dabbled in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English porcelain and bone china. It was impossible not to be struck by the ‘Chinoiserie’ style of many of them, and I was turned aside to explore.

A few years later I began to collect Chinese ceramics, in total but admiring ignorance. I read around the subject a little and haunted the Portobello Road market (London) on Saturdays, carrying the regulation plastic supermarket bag. It was not long before I accumulated a largish number of damaged mediocre specimens of different periods (these were disposed of, painfully, at auction many years later: an overdue lesson in the financial realities of collecting). Eventually I gained courage to enter some of the specialist (upmarket) dealers, but I desisted when I found that I could not carry on any meaningful conversation. In general the dealers were friendly and encouraging to a tyro who did not know what he was looking at, and evidently had no money. (Prices that are unmarked or marked in code are about the biggest turn-off I know – a dealer once told me his prices were in code ‘to help the customer’, though I have never found it helped me).

Gradually I began to learn and to accumulate a library, a major requirement for anyone who is beginning to collect seriously, however repetitious some of them are. I found that collecting provided an agreeable intellectual refreshment, valued in being totally divorced from my academic medical career, and ‘something to come home to’ at the end of the day; this became important to me. Roger Bluett (dealer) was pleased to feel he was not ‘only’ a dispenser of luxuries to the rich. It took me a long time to appreciate that I should cease buying pieces because of what they were or because they represented a period or ‘filled a gap’ or were rare (sometimes unkindly called ‘stamp-collecting’). This course, a shoestring imitation of the British Museum, turned out to be wrong for me, but I do not imply it as wrong for everyone; it all depends on what you like.

I realised instead that what I needed to do was to educate my taste, and to decide what reliably gave me renewed pleasure every time I looked at it. And I also recognised truth in some of the various deeper analyses of the psychology of collecting.

PSYCHOLOGY OF COLLECTING

Werner Muensterberger (a psychoanalyst who knows collectors well) writes: ‘The elation over a successful find or acquisition is bound to pass sooner or later. Once the object has been incorporated into the collection and the initial affective sensation, the joy, the pride, the novelty have worn off, the unconscious memory of early longings reemerges in accordance with the mental processes of the return of the repressed.’ What is repressed is, it seems, a need for ‘symbolic substitutes to cope with a world he or she regards as basically unfriendly, even hazardous. So long as he or she can touch and hold and possess and, more importantly, replenish, these surrogates constitute a guarantee of emotional support.’ It is not necessary to subscribe to the whole apparatus of Freudian psychoanalysis to profit from the author’s dissection of the passions and motives of collecting.

Muensterberger humbles collectors as he proceeds:

I have followed the trail of these emotional conditions in the life histories of many collectors. They reveal the need of the phallic-narcissistic personality. We see them in show-offs of all kinds. They like to pose or make a spectacle of their possessions. But one soon realizes that these possessions, regardless of their value or significance, are but stand-ins for themselves. And while they use their objects for inner security and outer applause, their deep inner function is to screen off self-doubt and unassimilated memories. The roots of their passion can almost always be traced back to their formative years, often hidden from their conscious awareness. In the light of these personal histories, sometimes remembered, in other cases reconstructed, or only perceived as hurtful or arduous, we see how collecting has become an almost magical means for undoing the strains and stresses of early life and achieving the promise of goodness.

So now we know.

Sigmund Freud’s study at his house in London, where he had fled from Vienna in 1938, still contains his original possessions (now the Freud Museum – visit recommended). The Museum records that ‘he confessed that his passion for collecting was second only to his addiction to cigars’.

The collection itself reflects the taste of someone more concerned to accumulate objects with meaning for him than to acquire items which would be impressive to a small band of fellow collectors. By 1939 Freud had amassed over 2000 objects and the collection encompassed items from the ancient Near East, Egypt, Greece, Rome and China…It fills the study and the front room. These antiquities created an extraordinary interior work space which was even to survive the move to another country. Today’s visitors to the study in London are often astonished to see that Freud worked in a museum of his own creation.

Freud himself considered that a collection to which there are no new additions is really dead.

A by-way of collecting psychology is explored by the acclaimed Jean Baudrillard, French philosopher and sociologist who, embellishing Marshall (the medium is the message) McLuhan, suggests that film, television, and now the Internet have created a culture of ‘hyperreality’ in which real life takes a back seat to simulated objects and experiences. This happens because simulations, unlike real things, can be endlessly and perfectly replicated. We are ‘seduced’ by the simulation’s aura of perfection. It begins to appear, Baudrillard says, ‘more real than reality.’ (In 1925 Henry Ford told the picture dealer René Gimpel that ‘he prefers the photograph of a picture to the picture itself.’) Baudrillard’s interests extend to collecting, of which he asserts that any given object ‘can be utilized, or it can be possessed…the two functions are mutually exclusive.’

With the onset of puberty, the collecting impulse tends to disappear…Later on it is men in their forties who seem most prone to the passion…the activity of collecting may be seen as a powerful mechanism of compensation during critical phases in a person’s sexual development. Invariably it runs counter to active genital sexuality (which it does not substitute but is) rather a regression to the anal stage.

Here indeed lies the whole miracle of collecting. For it is invariably oneself that one collects…

and so on.

A commentator from the University of Texas (Douglas Kellner) writes:

Widely acclaimed as the prophet of postmodernity, [Baudrillard] has famously announced the disappearance of the subject(s), political economy, meaning, truth, the social, and the real in contemporary social formations.

But some collectors may prefer the more comfortable traditional view of collecting held by W.B. Honey of the Victoria and Albert Museum. He wrote:

The practice of collecting objects of art has often been derided by the dull. They taunt the collector (with irrational and useless behaviour). To all this, most collectors will reply that they do not collect on principle or as a public duty, but to get a private and quite useless pleasure for themselves. They collect because they are fond of pottery, or whatever their quarry may be; only a poor-spirited collector will acquire objects that are merely representative or instructive or useful. And in this they are right. Collecting must be inspired by love and understanding. Knowledge and a rational purpose will not do.

It must of course be granted that there are some collectors whose enthusiasm has degenerated into a magpie lust, a mere cacoethes colligendi. Others want no more than to be in fashion…Some, again, indulge in ‘sentiments about sentiments’ by buying for the sake of associations plates with the arms of Lord Nelson, or jewelled cabaret sets declared (as a rule falsely) to have belonged to Marie Antoinette. Others assemble figures of dogs, or horses or admirals, out of affection for these subjects, or confine their attention exclusively to teapots or custard cups of every make and date. Some there are (it must be admitted) whose thoughts are of increasing values and social prestige. But the true amateur collects out of devotion to beauty, though he may never avow it, fondling his toys, like the Emperor Ch’ien Lung.

Sir Alan Barlow, in his Presidential address to the Oriental Ceramic Society in 1936, said of the collector:

If the private collector is accused of being a selfish and acquisitive parasite, addicted to envy, malice, and uncharitableness, the credulous victim of changing fashions or false standards, his reply must broadly be that he is helping in the accumulation and diffusion of knowledge and taste.

Of experts, he said: I have a prejudice against experts. As a civil servant I find them a perfect pest…;

and, relenting somewhat:

You cannot blame the professional expert for reticence; he knows the limitations both of our knowledge and of our intelligence…The expert who knows or fears that he may be quoted may well be reluctant to express a qualified opinion, which may be the most he can give, however great his desire to help the puzzled collector or the dealer purely anxious for knowledge.

Roy Davids, collector, scholar, writes:

In my view, they unnecessarily demean collecting who find it merely in their fundament — it is not just an involuntary act of anal retention. Nor is collecting just a matter of adult ‘transitional objects’ (‘comforters’) or merely a reaction to having had less than ‘good-enough’ parents. Though these, and perhaps the need for relationships that are at once both inspiring and unchallenging (the dead can’t answer back), as well as all sorts of possible projections, reassurances, controls, compensations, substitutes, displacements and dependencies, are all too real enough and undoubtedly are among the primary forces that drive collectors. But why must an exposure of such causes belittle all their effects? A capacity for solitude, so essential to creativity, is also a desideratum in collectors…

Happiness does not consist only of its most exuberant expressions — joy and elation. Across its whole gamut, both the cognitive and emotional, happiness also (including self-improvement), enjoyment, excitement, absorption and fun. In some prioritised indices of happiness, relationships with like-minded companions (and the worlds of rewards that they bring) and satisfying work and active leisure are accounted among the most important sources of well-being. Collecting undoubtedly serves many people beneficially during their lives in these respects…

And the ones who get most out of the past are those who put most into it, who relive it imaginatively; who place themselves in the driving, or at least the passenger, seat of history. It happens that collectors are more or less propelled by the need to possess, some

- Sir Alan Barlow 1881-1968ou cannot blame the professional expert for reticence; he knows the limitations both of our knowledge and of our intelligence…The expert who knows or fears that he may be quoted may well be reluctant to express a qualified opinion, which may be the most he can give, however great his desire to help the puzzled collector or the dealer purely anxious for knowledge.

Even Freud thought his collection of antiquities an essential part of what raised his life above that of the mediocre bourgeois professional.

Nor should it be forgotten or under-esteemed that collectors serve as custodians in preserving the past…

Collectors invest their personalities, as well as their pockets, in what they do, both in the selection of material and the work they do on it. Librarians and scholars (which is not to deny or denigrate what they do) cannot make the same sorts of contributions that come from the compulsive obsessions and commitments of collectors or the opportunities and freedoms open to them. A good collection, properly described, is almost by definition greater than the sum of its parts. In some degree, it is a creative process…

Lord (David) Eccles (1968) considered that ‘a collector is unfair to objects of beauty unless he takes the trouble to show them in an appropriate and enhancing manner’.

Collectors should weed out not only to raise cash, or just to ease the overcrowding, but to give their taste a chance to change. Nothing will keep them young and lively in the search for beauty like a collection that is always on the move.

The owner of a rare object will mention with satisfaction that it once formed part of a celebrated collection…(revealing) how the lonely vulnerable man of the present longs to enlarge his own personality by the capture of some fragment from the past, linked with a great name or recognized as a work of art not susceptible to fashion.

The chief personal motives for collecting are the search for beauty, the desire for continuity with the past and for the power of an age that has gone, the wish to participate in the creation of works of art, fetishism, the passion to complete a series; of these the search for beauty should always be dominant.

Most of my mistakes (of acquisition) were caused by being in too much of a hurry.

As Henry Moore says, very truly, more people are shape-blind than colour blind.

If you want to make a fine collection always insist that what you feel about an object is more important than what you know about it. (But Freud confessed his inability to appreciate beauty in art in any other way than by analysing and understanding it.)

As Sir Herbert Read frankly admits, the expert despises the collector. This book has come out in favour of the collector, because my own experience of pleasure from feeling the beauty of an object has been higher than my satisfaction in knowing what it is and all about it.

Trying to predict how we shall try to escape from the uniformity of mass products by collecting, I have come to the conclusion that three-dimensional objects give the greatest satisfaction.

DEALERS AND EXPERTS

The decision to purchase must necessarily be made in a short time; I am, perhaps stupidly, reluctant to take a piece home on approval; and the expectation that a piece will deliver repeated and long-term pleasure is often, but happily not always, in the event, disappointed. I have found that the immediate impact, at the first sight of a piece has, after years, become for me a reasonably predictable, though not infallible, guide. I have since been told that I only confirm what ‘everybody’ knows, but had not told me. Rigid reliance on this principle can lead to long periods without any purchase, which may become unendurable. However, the enviable experience of Kao Lien, writing in 1591, is not granted to everyone; ‘It is impossible to foretell to what point the loss of these ancient wares will continue. For that reason I never see a specimen but that my heart dilates and my eye flashes, while my soul seems suddenly to gain wings and I need no earthly food, reaching a state of exaltation such as one could scarcely expect a mere hobby to produce’ (quoted by G.St G.M. Gompertz from a translation by Arthur Waley, 1924-1925).

Taste can be educated by looking, handling, talking, listening, reading, and especially by cultivating a relationship with sources of supply, i.e. dealers who have a deep knowledge of their subject (not all have this), and who are willing to talk. Ideally they will telephone you when they have a piece that they know you will like and (very important) is within your price range. Such a relationship, of course, is reciprocal; it requires that you make purchases at reasonably frequent intervals.

Access to the right (for oneself) dealers is of the first importance, and is always available, which museum staff cannot be, and in any case dealers handle a continuous and copious stream of new material, increasingly laced with fakes, so that their reputation, and livelihood, are at risk, which concentrates their minds.

Many years ago, after a consultation on a supposedly eighteenth-century robin’s-egg-glazed parrot, with Roger Bluett, I suggested that it would be useful to collectors if he were to write a book encapsulating the expertise that he had just shown to me in ‘demoting’ the parrot (‘It is not as old as you are’). I did not care how old it was, but I did want the right price. He was horrified. ‘Absolutely not,’ he said. This opened my naïve eyes to the fact that dealers’ practical expertise is hard won and is very much what draws collectors to them; it is not something to be lightly given away. In any case some finer aspects cannot be clearly expressed in words, involving ‘eye’ and ‘feel’ and even intuition as to whether a piece is ‘right’; my assent to this is the result of having often examined a piece together with a dealer; it is, of course, what experts have always told me.

I gladly acknowledge the contributions to my education and collecting made by my knowledgeable friends and acquaintances; they know who they are.

I turn aside to consider just what is an expert? A benign (to experts) definition would be that experts are people whose knowledge, experience or skill causes them to be regarded as authorities, to have intellectual ascendance over the opinions of others and to be ‘entitled’ to be believed. But when contemplating a purchase at, or even above, one’s own realistic price limit, it is well to recall the mocking assessment of a former President of France (Georges Pompidou), that there are, for a man, three roads to ruin: women, gambling and taking the advice of experts. Women provide the most pleasant, gambling the quickest, but taking the advice of experts the surest (see also Barlow, above).

- D.R. Laurence MD, 2003Taste can be educated by looking, handling, talking, listening, reading, and especially by cultivating a relationship with sources of supply, i.e. dealers who have a deep knowledge of their subject (not all have this), and who are willing to talk.

GAINING KNOWLEDGE

The viewing and handling of as many pieces as possible is important right from the start, but Soame Jenyns was right when he said ‘There is nothing like buying objects for oneself to enable one to distinguish between what is good and what is bad’ (in conversation with various friends: Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol.60, p. 159). He added that he would not mind occasionally inadvertently buying a fake because he would learn from the experience.

The writings of professional scholars play an indispensable role, for they have experience, knowledge and insight infinitely beyond what a recreational collector can ever accumulate (though there are a few notable exceptions, e.g. Sir Harry Garnerand Sir Michael Butler who have greatly added to scholarship). They survey the historical scene and are able to point out what is or was deemed good or bad taste, and why. Like any serious historian or critic they have some responsibility for impartiality if they value their reputations. Readers are annoyed if mere personal and unsupported opinions are thrust upon them by scholars. But yet the personal opinions of scholars are of interest to collectors, who have no need to follow them slavishly.

For a long time I have amused myself by collecting examples where those scholars best known to Westerners allow themselves to reveal (some never do) what they particularly, personally, like and admire, and also what they have no taste for. I like to relate my taste to theirs, and where there is difference I turn aside to look again at what I may too easily have overlooked or dismissed; and where there is accord I can indulge my vanity just a little.

I have foraged in their more accessible (though often out of print) principal works and have made a collection of their own words that have pleased me, and may perhaps please other collectors.

The following anthology is presented under the names of the scholars (it was not practicable to classify the quotations by period or by class).

My sources are necessarily confined to what has been published in English and I recognise that reliance on these sources means ignoring Chinese scholarship except where (too rarely) a translation is available: I wish there were more. But this is an entertainment for collectors suffering the same constraints as me. It can be no surprise that this situation vexes Chinese scholars, who see as inappropriate the prevalence of Western views due to lack of access to their scholarship for both linguistic and historical/political reasons; and indeed of access to their often different cultural attitudes to scholarship and taste. Chinese connoisseurship dates from the twelfth century; European scholarship developed only in the nineteenth, and even then was handicapped by lack of practical experience of early and Imperial wares, which had not then reached Europe in any quantity.

In preparing this anthology I have become aware of a thread of tactlessness and even sometimes of condescension as, for instance, one comment on a question of dating that the Chinese to a ‘surprising extent…may, despite Western disbelief, have been right all the time’. But bruised feelings are now happily being soothed (see below).

In 1953 Soame Jenyns wrote of Chinese texts:

The European student who attempts to trace a [Chinese] statement to its source or appraise its value is utterly bewildered. It may seem to Chinese eyes impertinent for the European [who in their terms has only recently even seen many of the important wares] to step into a field which, it may be argued, is more properly a Chinese province…

But scholarship of its nature cannot be constrained and it implies admiration.

In 1923 Bernard Rackham (Keeper of Ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum) told the Oriental Ceramic Society that it was ‘not until forty years ago that any pre-Ming ceramics were acquired’ by the Museum, after which twenty years elapsed before any further specimens arrived.

John Ayers writes in 1999:

The changes that the past fifty years have brought to our knowledge and appreciation of Chinese ceramics are indeed remarkable. The political revolution of 1949, which in many respects closed China to the outside world, caused a division in research between East and West that has happily been healing rapidly since the rapprochments of the 1970’s.

And the Oriental Ceramic Society now finances visits by Chinese scholars for lectures and discussions.

As long ago as the great International Exhibition of Chinese Art at the Royal Academy, London (1935-36), Western scholars seem to have been ready brusquely to tell the Chinese that they had misdated important ceramics specially chosen in and conveyed from China on the naval cruiser H.M.S. Suffolk. The Exhibition was indeed ‘a watershed in the general appreciation of the arts of China’, although ‘immediately in scholarly results it proved a disappointment’ (see Basil Gray, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 50, 1985-86, where, as the only survivor of the British [organising] Committee he provided a 50-year retrospect).

That the Exhibition was widely regarded as a great cultural (and political) occasion was confirmed by the patronage of the King and Queen and the President of the Chinese Republic. The Royal Academy demonstrated its practical commitment by its willingness to shore up the floor of its central octagon room to take a near nineteen-feet-high stone Buddha weighing over three tons.

Lu Yuaw (Consultant Curator, Art Museum, National University of Singapore), writes of the use of the term celadon for Chinese greenwares, commonly considered to be derived from a seventeenth-century mythical French shepherd (Céladon) who was clothed in green; a ‘conception hitherto held by those collectors whose knowledge of Chinese ceramics has been nurtured on Western literature’. ‘I will now ring down the curtain on celadon and let greenware take the stage.’ He notes with approval that the museums at Oxford and Jakarta have ‘boldly discarded the term ‘celadon’ and, instead adopted the more appropriate one of ‘Chinese greenwares’ in (their catalogues)’.

Elsewhere he mildly censures viewers of a Song Ceramics exhibition ‘who have been long conditioned to fetishly worship the word, for example, of London antique dealers rather than listen to the views of Chinese ceramicists based on archaeological evidence’; and he spells out the Chinese and Western perceptions of what is porcelain:

To the Chinese a ceramic ware made of kaolin, fired to fusion at around 1300°C, with the finished product little or non-absorbent to water and giving out a clear ring when struck; if these conditions are met, the resulting product is accepted as porcelain.

Ceramicists in the West, on the other hand, demand additional conditions, e.g. pure whiteness and a degree of translucency. By Western criteria, therefore, few of the Song ceramic wares, including all the ‘imperial’ types, would qualify for porcelain except qingbai ware of Jingdezhen and perhaps the finer grades of Ding ware…

Philip Rawson points out:

Practically all the finest high-fired, hard-paste porcelain of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe – especially made by casting and jiggering – has the air of ‘don’t touch’ about it. It was…made primarily to be looked at, and to create a visual impression of high style and good taste (i.e. ‘ceramics as treasure’).

This distant impression can also seem very strong, at first sight, with some of the finest Yung-cheng and Chien-lung Chinese eighteenth-century porcelains. But we would be wrong to imagine that the cases are identical. There can be no doubt that a visual effect was actually one of the Ch’ing Chinese potters chief aims – many of the surface designs are virtually pictures; and mechanical manufacture of some sort was used under the almost incredibly perfect glazes. But in China we must never forget that there were at least two other dimensions to fine porcelain which we in the West have never learned to perceive; in fact we can scarcely do so even when they are pointed out to us…

First is the feel of the weight and body of the pot, with its glaze, in relation to its size…

The second special dimension in Chinese porcelain is sound. Everyone knows that porcelain rings when touched…The Chinese listen to porcelain as intently as they feel it…Nowadays only museum men (sic) and some dealers who handle pieces every day have developed even the most rudimentary sense of ceramic sound. It is impossible for the ordinary museum visitor to cultivate it at all; and many people may find it hard to believe in.

(Note: DRL: In the West, the notion that a clear ringing tone provides some assurance that the piece tapped/struck is intact, persists, yet every collector knows that a restored piece may yet ring clearly. Perhaps the Chinese connoisseur can discriminate by tones. The sound of dragging a coin on the rim of a piece to detect restoration makes me flinch).

- W.S Gilbert 1836-1911The meaning doesn’t matter if it’s only idle chatter of a transcendental kind

AN ART OR A CRAFT

‘The meaning doesn’t matter if it’s only idle chatter of a transcendental kind’ (W.S. Gilbert, 1836-1911).

Since Britain supports, by public funding, both an Arts Council and a Crafts Council it is evident that many people think the distinction does matter. ‘The word ‘craft’ cannot do justice to the variety and ingenuity of the decorative and applied arts in Britain’ (British Council). The distinguished American oriental scholar, Sherman Lee, interviewed for Orientations (February 1998), was asked about the relationship between ‘art’ and ‘craft’. He replied that, ‘with craft you can never get enough perfection’ and instanced the netsuke, ‘but it ain’t worth it’. A sculptor trying to advance his art may fail in craft and technique but succeed ‘in fervour and desire. Everyone can judge the craft, but not everyone gets the art’. ‘Qing period lacquers, jades, and porcelains are overworked, over-finished and over-refined, but where is the art?’

Bernard Leach wrote (1940) ‘In our time technique, the means to an end, has become an end in itself, and has thus justified Chinese criticism of us as a civilisation ‘outside in’‘.

William Burton wrote in 1906:

With this reign [Qianlong] we reach a period when artists and collectors frequently part company in the extent of their appreciation of Chinese porcelains. The loss of freedom and breadth, as well as of the rich colouring of previous ages, which the artist deplores, is more than compensated for, in the eyes of collectors, by the fitness and perfection of the material and the increased delicacy and precision of the painting.

COLLECTOR, CONNOISSEUR, DEALER, PROVENANCE, FAKES

The psychoanalyst Werner Muensterberger writes, that even though the possessions are only external tokens, their significance in the collector’s experience represents a salient distinction between the connoisseur and the collector. ‘A connoisseur may cherish or admire an object, but receives little emotional support from its ownership’; ‘there is no affective attachment to the object’; ‘he does not need to own the object and can live without it’; ‘the committed collector, on the other hand, cannot.’

The dealer does not perceive as deprivation the special efforts made to acquire and sell anything warranting collecting. ‘In experiential terms, the dealer is the dispenser or supplier of magic objects…the self-assured dealer adds nimbus to the object’; the ingenious dealer thus has a kind of ‘shamanistic power’. Collector-dealer relationships are an interplay between the needful collector and the astute and empathetic dealer. ‘The notion of being the preferred customer or, in emotional terms, the best-loved child appears then as a source of relief and assurance, while revealing an infantilized aspect in the collector’s personality.’

Provenance, a reliable source and a list of previous owners and exhibitions where a piece has been shown is like a borrowed genealogy, especially where the items suggest special status. In more mundane terms, a longstanding and reliable provenance gives some protection against recent fakes and disputed ownership.

Fakes. In the Preface to the British Museum exhibition Fake? The art of deception (1990) David Wilson asks the ‘final question…that appears to be unanswerable…why does an object which is declared a fake lose value immediately?’

Roy Davids offers:

An object exposed as a fake loses those magical qualities we invest in it as a real link to the past and our own place in the human continuum as well as its value for research and use for comparison. It also too uncomfortably confronts us with our own fallibility and foolishness.

THE ANTHOLOGY BY AUTHOR, IN APPROXIMATE CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

‘When referring to a second-rate collector the Chinese say “he has ears but no eyes”, meaning that his judgement is based on hearsay, on the opinions of others, rather than on close observation’ (René-Yvon Lefebure d’Argencé, in Orientations, January 1998, p. 59).

THE AESTHETICS OF REPAIRED PORCELAIN

Philip Rawson writes:

‘We can read in Chinese literature of servants being severely flogged for breaking precious porcelain food vessels. Partly as a function of this latter attitude Western collections contain fine pieces which have been repaired in China with malleable gold along the breaks, thus subtly indicating the value of the piece even when broken and at the same time allowing the repair to contribute to our understanding of its inner structure and individual history.

Anthony du Boulay writes of his ‘small Jun bubble cup, broken into six pieces and repaired in gold lacquer.

Despite this damage, which could put it out of court for many collectors, it is one of the most expensive pieces in [my] collection. In my opinion its beauty is enhanced by the repair, and if future circumstances were to allow me to retain only one piece this probably would be the one.’

A vision from People of craftmanship and scholarly knowledge

A. Pellet, London

Letter to E. Parker, 1754, from ‘An Inventory of Queen Anne of Denmark’s Ornaments…1619’: ‘The nanquen sort is much the present taste and consequently the dearest, but as tis only blue and white will not be thought so fine. However you may have a good, genteel, full, set (that is 42 pieces) for about 5 or 6 guineas since the Beau Monde is chiefly for the ornamental china.’

Thomas Babington Macaulay

Lord Macaulay, historian, writing in his History of England (published 1849-1861) gave one view of taste for oriental ceramics in the late seventeenth century during the reign of William and Mary. At Hampton Court Palace: ‘In every corner of the mansion appeared a profusion of gew-gaws [showy but valueless trinkets: C15: of unknown origin], not yet familiar to English eyes. Mary had acquired at The Hague a taste for the porcelain of China, and amused herself by forming at Hampton a vast collection of hideous images, and of vases on which houses, trees, bridges, and mandarins were depicted in outrageous defiance of all the laws of perspective. The fashion, a frivolous and inelegant fashion it must be owned, which was thus set by the amiable Queen, spread fast and wide. In a few years almost every great house in the kingdom contained a museum of these grotesque baubles. Even statesmen and generals were not ashamed to be renowned as judges of teapots and dragons: and satirists long continued to repeat that a fine lady valued her mottled green pottery quite as much as she valued her monkey, and much more than she valued her husband.’

But Macaulay adds a footnote: ‘Lady Mary Wortley Montague took the other side. “Old China” she says, “is below nobody’s taste, since it has been the Duke of Argyle’s, whose understanding has never been doubted either by his friends or enemies”.’

Reitlinger considered that Macaulay’s opinion ‘was in line with well-informed [mid-19th century] taste in this matter’ and ‘would have entirely fitted in with the views of Ruskin’. Another critic remarked that Macaulay was a Puritan and therefore hated all art.

With regard to perspective Margaret Medley writes of seventeenth-century porcelain painters that they developed ‘a new skill in handling the brush and in carrying over into porcelain decoration a painter’s eye that penetrates the very structure of landscape in a quite revolutionary manner’

Regarding perspective, William Watson remarks in relation to Tang dynasty art: ‘Nevertheless, to modern critics for whom success in creating the illusion of receding space is a yardstick of progress – never mind how far that idea from Tang theorizing – there are signs that the landscape compositions of the eighth century had reached a peak.’ He adds that there are even suggestions of the vanishing-point perspective of post-Renaissance Europe in landscapes of the Buddhist murals at Dunhuang (caves).

Friedrich Perzynski (1910-1913)

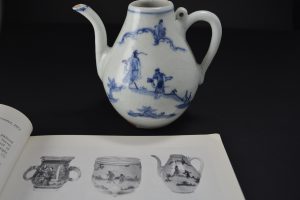

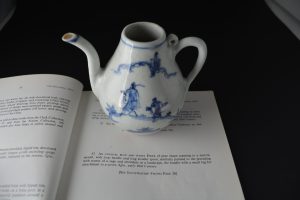

Perzynski’s name, in English language literature, seems to be remembered for a single (minor) passage in his writing, where he coined the term “violet(s) in milk” for a “velvet-like shimmer” of the “peculiarly vivid blue” of seventeenth-century Transitional porcelain. (A practical attempt by myself to replicate the analogy did not convince). The quality of his assessments deserves better, as follows:

(The four articles are of their time in their frequent reference to and extrapolation from single items in private and public collections, e.g. in the British Museum to a plate being ‘in Case II on the bottom shelf of the case at the far end on entering from Room 144’ (a recent search failed to discover it)).

A Wanli bowl at the South Kensington Museum [now the Victoria and Albert Museum] ‘contradicts the supposition, held by all other writers without exception, that the Wanli period only produced blue-and-white porcelains of secondary value, and that it was a period of decadence’.

‘Anyone who has realized the fact (many never do) that the Chinese used their porcelains as a ground for paintings…will find this (bowl) worthy of more esteem than can be given to the K’ang-hsi decorators.’

‘The porcelains painted in under-glaze-blue during the later years of Wanli’s reign and the transitional period between the Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties are usually summed up contemptuously under the name of “Export-goods”.’

‘The excessive ornament has become the main object of the work instead of form, substance and glaze – the true end of ceramics.’

‘The K’ang-hsi period is generally esteemed in Europe “the golden age of Chinese potters”, and K’ang-hsi porcelain, including blue and white underglaze, the “culminating period of ceramics”. Will the serious [Chinese] history of Chinese art which still awaits a writer confirm European judgment?

‘It is difficult to understand why the Chinese…during the time of K’ang-hsi and of his ingenious successor Yung Cheng should have been continually striving to imitate ancient examples.’

‘In wading through the spiritless fabrications of the Ching dynasty and the more vigorous personal Ming art to the delicate invention of the Sung period, we reach at last the most perfect expression in casting in some Shang ritual vessel. There, both outline and ornament seem inevitable growths, and we feel that the long solemn reverence – even approaching to adoration – paid to these bronzes originates not only in religious sentiment, but also in an equally lasting aesthetic impulse.

‘The feeling of the serious student of ceramic art will probably not be altogether dissimilar. Even if two-thirds of the very numerous Han and Tang figures now found in tombs are merely clever imitations by Japanese dealers – as I do not doubt they are – the genuine remainder always show very highly developed skill and no sign whatever of primitive handling.

Chinese connoisseurs place the climax of ceramic development some centuries further on, in the later Chou and during the Sung periods. No scholar has yet given us any account of the masterpieces made before and after the Sung period which may still exist in the collections of Chinese grandees, but the few Sung types known to us are perfect creations of the ceramic spirit as regards the grace and purity of their forms, the delicacy of their decoration, and the richness of their glaze almost attaining the living quality of skin. They make it clear that the line of development tends to increased luxuriance rather than to more intrinsic animation of form.

The Ming ceramists, though still under the impulse of mediaeval vigour, followed on this line. What great accomplishment could be reached in the sphere of ceramics when such subsidiary architectural details as symbolic ridge-tiles absorbed so much of the most brilliant workmanship and subtlest artistic knowledge then at the service of ceramic sculpture?

‘The emperor K’ang-hsi, a great man as well as a great sovereign, bore on his shoulders the overpowering burden of this ancient, almost spent, culture. Yet to him and his ceramic craftsmen belongs the merit of having transformed the catastrophe of declining ceramic art into a noble and fascinating finale. For though its form and decoration often lack the charm of personality, they never wholly belie the nobility of established taste, while it is under their fascination that their late, and feeble, European derivatives have for more than two centuries borrowed warmth and resplendence from the glory which they reflect.

‘The first years of the reign of the young Manchu emperor were full of internal troubles; and as late as the early seventies of the seventeenth century the Ching Te Chen kilns were destroyed by the rebels. The time of the highest technical perfection should therefore logically be placed in the middle period – i.e., after the reconstruction of Ching Te Chen (1677) and the appointment of Ts’ang Ying-hsuan as superintendent of the imperial factories (1683).

‘The porcelains of the first years of K’ang-hsi’s reign remind us in their character of the not very refined style of the transition period (1620-1660). The paste is heavy, the glaze is often not quite faultless as well as somewhat greenish, the form is unrestful, and has not yet attained that rather cold beauty which marks the highest technical achievement. The decoration, too, reveals the proximity of the Ming period, and consequently the influence of the Persian ceramists. It is arranged more in accordance with pictorial principles than with the rules of severe symmetry. The blue is slightly or not at all shaded, and is sometimes peculiarly heavy, though it is remarkably effective as decoration.

‘Pictorial composition as decoration for blue-and-white porcelain was cultivated more eagerly in the Ming than in the K’ang-hsi period. The style of porcelain decoration of this period may be considered too cold and polished. It must, however, be acknowledged that under this reign a purely ornamental style had also developed, forcing men and landscape into its frames so that what both lose in naturalness is gained in symmetry and balance as regards decorative effect. A typical example of this is furnished by “the Master of the Rocky Landscapes”*, as I will call him, in a motive copied ad nauseam more or less freely by him and artists of minor factories also. It depicts “the two friends” or a scholar with his attendant enjoying the charms of an impossibly picturesque mountain landscape, one scene or a whole series illustrating the various stages of their pilgrimage, which runs round the body of the vase. Rocks and mountains of similar formation and also groups of trees occur again and again, apparently taken from a sample-book. Close to a tree luxuriating in its full foliage another almost leafless or decayed is placed in effective contrast.’

[Note. Gerald Reitlinger coined the useful term ‘Master of the Rocks’ which refers to a specific easily recognized style of Transitional porcelains with which anyone who has an interest in seventeenth-century porcelain is familiar.]

R.L. Hobson (1915)

‘The antiquity of Chinese porcelain, its variety and beauty, and the wonderful skill of the Chinese craftsmen, accumulated from the traditions of centuries, have made the study of the potter’s art in China peculiarly absorbing and attractive. There is scope for every taste in its inexhaustible variety. Compared with it in age, European porcelain is but a thing of yesterday, a mere two centuries old, and based from the first on Chinese models. Even the so-called European style of decoration which developed at Meissen and Sèvres, though quite Western in general effect, will be found on analysis to be composed of Chinese elements. It would be useless to compare the artistic merits of the Eastern and Western wares.

‘It is so much a matter of personal taste. For my own part, I consider that the decorative genius of the Chinese and their natural colour sense, added to their long training, have placed them so far above their European followers that comparison is irrelevant. Even the commoner sorts of old Chinese porcelain, made for the export trade, have undeniable decorative qualities, while the specimens in pure Chinese taste, and particularly the Court wares, are unsurpassed in quality and finish.’

‘If the newspaper account was correct, there was an incident in the recent revolution which should touch the collector’s heart. A prominent general, who, like so many Chinese grandees, was an ardent collector, was expecting a choice piece of porcelain from Shanghai. In due course the box arrived and was taken to the general’s sanctum. He proceeded to open it, no doubt with all the eagerness and suppressed excitement which collectors feel in such tense moments, only to be blown to pieces by a bomb! His enemies had known too well the weak point in his defence.

‘Collecting is a less dangerous sport in England; but if it were not so, the ardent collector would be in no way deterred. Warnings are wasted on him, and he would follow his quarry, even though the path were strewn with fragments of his indiscreet fellows.’

‘The Sung is the age of high-fired glazes, splendid in their lavish richness and in the subtle and often unforeseen tints which emerge from their opalescent depths. It is also an age of bold free potting, robust and virile forms, an age of pottery in its purest manifestation.’

‘Blue and white and polychrome porcelain chiefly occupied the energies of Imperial potters at Ching-te Chen in the Ming dynasty…[who] painted with more freedom and individuality.’

‘In the Ch’ing dynasty the appetite of the Ching-te Chen potters was omnivorous and their skill was supreme.’

‘As far as our present (1915) knowledge of the subject permits us to see, there is nothing in the pre-Han pottery to attract the collector. It will only interest him remotely and for antiquarian reasons, and he will prefer to look at it in museum cases rather than allow it to cumber his own cabinets. With the Han pottery it is otherwise. The antiquarian interest…is now supplemented by aesthetic attractions.’

‘Our knowledge of T’ang pottery has only just begun…here, at last, we have the great art which inspired the early Buddhist sculptors of Japan.’

‘The Lung-ch’uan celadon glaze is singularly beautiful…The ware has enjoyed immense popularity in almost every part of the world for untold years.’

Of architectural pottery:

‘Many of the ridge tiles, with figures of deities, horsemen, lions, quilin, and phoenixes have found their way into collections to which their spirited modelling has served as a passport.’

‘The Ch’eng Hua porcelain shares with that of the Hsuan-Te period the honours of the Ming dynasty, and Chinese writers are divided on the relative merits of the two.’ R.L. Hobson writes that genuine examples of both reigns are virtually unknown in Western collections.

On Kraak wares:

‘The finer examples of this group are of admirable delicacy both in colour and design; but the type lasted well into the seventeenth century and became coarse and vulgarised.’

On Wanli wucai:

‘The object of the decorator seems to have been to distract the eye from the underlying ware, as if he were conscious of its relative inferiority.’

‘But the Fukien porcelain [Dehua: blanc de Chine] par excellence is a white ware of distinctive character and great beauty which was and still is made.’ The nature of the ware makes dating difficult, ‘viz whether it is Ming or early Ch’ing. The nature of the ware itself is a most uncertain guide…The influence of the Te-hua wares is obvious in many of the early European porcelains, such as those made at Meissen, St Cloud, Bow, Chelsea.’

The wares of the last three Ming emperors (1620-1643) are generally ‘of little merit’, ‘coarse, the design crudely drawn, and the colour impure’.

‘Meanwhile, we pass to the reign of K’ang Hsi (1662-1722), the beginning of what is to most European collectors the greatest period of Chinese porcelain, a period which may be roughly dated from 1662-1800. Chinese literary opinion gives the preference to the Sung and Ming dynasties, but if monetary value is any indication the modern Chinese collector appreciates the finer Ch’ing porcelains as highly as the European connoisseur.’ [Ming wares of high quality had not then been ‘fully appreciated’ due to ‘lack of adequate representation’ in the West.]

‘The choicest blue and white of this period [K’ang Hsi] was unsurpassed in the purity and perfection of the porcelain, in the depth and lustre of the blue, and in the subtle harmony between the colour and the white porcelain background…The [base] patch of glaze is usually pinholed, as though the nemesis of absolute perfection had to be placated by a few flaws in this inconspicuous part.’

‘Perhaps the noblest of all Chinese blue and white patterns is the prunus design (often miscalled hawthorn)…The form is that of the well known ginger jar, but these lovely specimens were intended for no banal uses [they were filled with gifts, e.g. tea] but it was not intended that the jars or boxes should be kept by the recipients of the compliment [the design has become vulgarised]…But nothing can stale the beauty of the choice K’ang Hsi originals…The amateur should find no difficulty in distinguishing these from their decadent descendants.’

‘The noblest examples of [K’ang Hsi polychrome porcelains] and perhaps the finest of all Chinese porcelain, are the splendid vases with designs reserved in grounds of green, black, yellow or leaf green…Today they are rare, and change hands at enormous prices. Consequently all manner of imitations abound, European and Oriental…’

On famille verte:

‘To obtain full tones and the contrast between light and shade…it was necessary to pile up the layers of colour at the risk of unduly thickening the enamel. But the connoisseur of today finds nothing amiss in these jewel-like incrustations of colour…The zenith of this style of decoration was reached about 1700, say between 1682 and 1710′. Later famille verte lost vigour, becoming decadent, ‘heralding the more effeminate beauty of famille rose’.

Dating of K’ang Hsi monochromes is particularly difficult: ‘The careful student observes certain points of style and finish, certain slight peculiarities of form which are distinctive of the different periods, and on these indefinite signs he is able to classify the doubtful specimens. To the inexpert his methods may seem arbitrary and mysterious, but his principles, though not easy to enunciate, are sound nevertheless.’ (This seems to be the ultimate defence or exposition of connoisseurship: scholarly dealers live by it and it is impressive to see it in action.)

Ch’ing celadons are ‘wanting in the peculiar solidity of appearance of the ancient wares’.

‘The claire de lune or moon white…, an exquisite glaze of palest blue.’

Of Qianlong: ‘The Imperial wares attained their greatest perfection at this time.’

‘It is stated on the authority of M. Billequin…that “a sumptuary law [i.e. a law controlling extravagance] was made restricting the tea dust glaze to the Emperor, to evade which collectors used to paint their specimens with imaginary cracks, and even to put in actual rivets to make them appear broken”.’ (I would be grateful to be told where such a piece may be seen. DRL)

‘In the Ch’ien Lung period Chinese porcelain reaches the high-water mark of technical perfection. The mastery of the material is complete. But for all that the art is already in its decline…In detail the wares are marvels of neatness and finish, but the general impression is of an artificial elegance from which the eye gladly turns to the vigorous beauty of the earlier and less sophisticated types.’

‘Porcelains with European pictorial designs are, as a rule, more curious than beautiful…but [those] with European coats of arms emblazoned in the centre [are] highly decorative.’

Some [blank] Chinese porcelain was sent to Europe for decoration there, ‘but [in addition] there is a large group of hideously disfigured [in Europe] wares known by the expressive name “clobbered china” [having coloured enamel overpainting of underglaze blue and white]…the effect is laughable, but it was vandals’ work…’.

‘The reign of Tao Kuang is the last period of which collectors of Chinese ceramics take any account…It seemed as though the wells of inspiration in China had dried up…The Peking or medallion bowls, for instance, are little if anything below the standard of previous reigns…The collector will always be glad to secure specimens of the palace porcelains of the Tao Kuang period and of the smaller objects [e.g. snuff bottles] on which the weakness of the colouring is not noticeable.’

‘But the collector’s interest in Kuang Hsu porcelain is of a negative kind. When it is frankly marked he sees and avoids it.’

‘The brief reign of Hsuan T’ung (1909-1911) is a blank so far as ceramic history is concerned.’

On the Western judgment of the Qing dynasty: ‘Nothing can surpass the simple rounded forms which sprang to life beneath the deft fingers of the Chinese thrower…and their wheel-work rarely fails to please.’

A.L. Hetherington (1924)

‘There is already a rapidly-growing body of collectors who are losing their interest in the more elaborate productions of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and are collecting in their place the simpler types and the purer art exhibited by the wares of T’ang, Sung, Yuan and Ming dynasties…When we come to the reign of K’ang Hsi, we begin to see signs of over-elaboration, which is hardly in keeping with the material, though the art may still be said to be “suitable”. But the wonderful porcelains of the Yung Cheng, and more particularly those of the Ch’ien Lung reign show pronounced signs of what may be called “unsuitable” art; by which I mean that the beautiful pictures depicted in enamels on the potter’s medium would find a more appropriate place on the silk or canvas of the artist.’

‘It would not be difficult to cite instances of people who are left quite cold by an inspection of eighteenth-century potting of distinction, but who wax enthusiastic over a piece of Lung-ch’uan celadon. The reader will be saying that this is merely an ex parte statement to be discounted accordingly…’

T.S. Eliot (1935)

‘Only by this form, the pattern, Can words or music reach The stillness, as a Chinese jar still Moves perpetually in its stillness.’

A.D. Brankston (1938)

‘If eyes may be acquired at all, for they are not saleable commodities, it is by constant handling and daily use of fine objects, whether they be bronzes, jades, paintings or porcelain.

‘To test the potentialities, drink tea each day from different cups; if possible, one should be of the fifteenth century and the others of various later periods. Then, after two weeks, if no particular piece has asserted itself, one may be assured that the interest in porcelain was formed only in order to create a diversion and to occupy time and space, so a change over to stamps or coins would be recommended.’

The early Ming wares are, ‘in the writer’s opinion, the summit of attainment in potters’ art at Chingtechen’.

‘These Ming wares have leaped a gap of five hundred years and hold the stored-up energy of those who made them. There is no trace of flavour or decay about them…Yet, today their use and true meaning are lost, our eyes may see and perhaps a shadow of purpose is felt…’

‘When one compares [a] K’ang-hsi piece together with the Yung-lo original, in sunlight if possible, there can be little doubt which is the finer…The Yung-lo piece carries more of the character of the man who made it.’

‘Shen Te-fu says that “during the Hsuan-te period potters were inspired by Heaven to produce works of subtle meaning and supreme artistry”. In handling such pieces one must agree with him.’

‘During the K’ang-hsi period potters and draughtsmen were able to imitate Ch’eng-hua pieces so well that little difference is noticeable.

Therefore, if we admire all Ch’eng-hua pieces we should also admire those of K’ang-hsi. This is not true of the finest Ch’eng-hua…’

- Bernard Leach (1887-1979)Very few people in this country think of the making of pottery [and porcelain] as an art, and amongst those few the great majority have no criterion of aesthetic values which would enable them to distinguish between the genuinely good and the meretricious.

Bernard Leach (1887-1979)

‘Very few people in this country think of the making of pottery [and porcelain] as an art, and amongst those few the great majority have no criterion of aesthetic values which would enable them to distinguish between the genuinely good and the meretricious.’

‘In the greatest period, that of the Sung dynasty…’

“Accepting a Sung standard” is a very different thing from imitating particular Sung pieces…We are not the Chinese of two thousand years ago…but that is no reason why we should not draw all the inspiration we can from the Sung potters.’

‘Of all pottery that of the Sung is most expressive of its material. It is in fact the purest of pottery.’

‘It is unfortunate that as a consequence of its divorce from life, the “applied” no less than the “fine” art of our time, more than in any other age, suffers from excessive self-consciousness.’

‘Of the world’s pots I would choose the Korean’s above all…The last thing in the world these people would think is that they were artists or craftsmen. They were people doing work as well as they knew how and getting as much satisfaction as a man could.’

‘In the nobility and universality of the best T’ang and Sung pots discerning minds have recognized the highest achievement and therein a measuring rod of values.’

‘We are left with the question of whether an unknown craftsman deserves to be put on a level with the best artist. My answer is yes, provided that humility and life are given expression.’

W.B. Honey (1945)

‘…appreciation of beauty is in its essence a simple thing, direct and not dependent on reasoning or even upon knowledge, scientific or other.’

‘To have learnt to see the whole work, and to have come under its spell, rather than attempt fruitlessly to analyse it into its meaningless parts, must be a first requirement in all art criticism.’

‘To appreciate the merits of a piece of pottery it is necessary at the outset to have a certain gift of eye…But even this gift must be cultivated.’

‘The service to posterity may perhaps be counted to the collector for righteousness, if his personal delight is held not to be enough.’

Honey describes ‘two aspects or tendencies in the Chinese mind and spirit’; first, the ‘Imperial’ or ‘official’ taste, ‘conservative and restrained, caring most for a smooth perfection’; and second, the wilder, adventurous and ‘romantic’ tendency, ‘the instinctive taste of the peasant craftsman himself, working in poverty, close to nature, as opposed to the luxurious taste of a leisured class of patrons’. These latter wares give ‘merit to much Chinese peasant pottery of kinds so little costly and so rough and “common” that they are virtually ignored by the official Chinese ceramic historian. Yet the wares of this order are often of the greatest beauty [with] a total disregard of mere smoothness and facility and mechanical perfection of finish.’

‘The Sung wares are peculiarly satisfying to the taste of the Western collector and potter of the present day…and it is hardly surprising that they should have been claimed as the best pottery ever made.’

‘The Ming taste largely reflected the Sung ideals with their preference for ancient forms and low-toned glazes, in favour of the brighter colour and variety of the T’ang.

‘The Te-hua porcelain at its best is one of the most beautiful ceramic materials ever made.’

‘Fifty years ago [i.e. circa 1900] the eighteenth-century monochrome wares were praised above all other Chinese porcelain. Nowadays, by an unnecessary comparison with the early wares, they are often described as slick and obvious in form and with their often brightly coloured glazes are relegated to a merely “decorative” class. But they have their own qualities – a Baroque splendour of colour, not without subtlety, and a range of clean, decided, masculine forms.’

‘The shapes that emerge under the potter’s hands are constantly changing as he works, and the form finally produced depends as much upon a critical sense in the potter…this is true of all throwing not mechanically and rigidly controlled by the use of profile and templet. The creation of a “good” or beautiful form is thus due, not only to the potter’s deliberate manipulation towards a desired shape, but to his judgment in deciding when to stop. It is not due, as is asserted in the romantic account of the matter given by a modern English artist-potter, “to life flowing for a moment perfectly through the hands of the potter”.’

‘Technical perfection here implies the masterly employment of means to an end; mechanical finish and precision are merits of another order.’

‘…the total impression given by a fine pot. To the connoisseur it should be like a piece of abstract sculpture, satisfying as a composition of mass and profile, appropriately finished [monumental or sensitively shaped, etc.]…it may rank among the noblest creations of man’s brain and hands.’

‘Appreciation of the pottery is moreover not increased, in my opinion, by a familiarity with the Chinese names for the various shapes and colours or by knowledge of the subjects illustrated in the decoration of porcelain. But these matters are often the subject of enquiry…’

In a reference to pieces [eighteenth-century] sent from the Imperial Palace Collection to the (London) Exhibition of Chinese Art in 1935: ‘the astonishing openwork “revolving vases”, those miracles of misapplied skill.’

Soame Jenyns (1904-1976)

‘A Japanese authority – Mr Kyoho Ueda – has unkindly divided experts in the field of Chinese ceramics into two schools. The first school he says is those who judge by experience; the second those who study books.’ Book knowledge ‘is at all times a poor substitute for touch and sight’.

‘The shapes of Ming pottery and porcelain, if we exclude the Imperial wares, are full of power. Massive and simple, they may be also clumsy and crude, but they are always strong. They show complete contempt for the niceties of finish.’

‘It is not surprising that the Mings called themselves the “bright” dynasty for the decoration of their pieces abounds in strong colours. The drawing is swift, and certain, if sometimes violent, and often delightfully impressionistic in the coarser pieces.’

Of the Yuan period:

‘Few pieces belonging to this period can be distinguished from the coarser products of the Sung dynasty whose traditions they continue in a poorer form.’

‘The ceramics of the Yuan period are rated by most collectors as of negligible importance.’ [But see Margaret Medley in this anthology.]

‘The study of Chinese ceramics from the Sung to the Ch’ing is likely to remain the province of the connoisseur, rather than that of the archaeologist or the art historian.’

‘The field of Ming ceramics is far more controversial than that of the Ch’ing. Many attributions must remain a matter of personal conjecture until time and usage has sanctified or rejected them. The museum official is a legitimate Aunt Sally in these controversies’; for it is the museum official’s job to make attributions and reattributions. [Aunt Sally is a game in which sticks or cudgels are thrown at a wooden (woman’s) head mounted on a pole, the object being to hit the nose of the figure, or break the pipe stuck in its mouth. The word aunt was anciently applied to any old woman (Brewer).]

‘There are thus many people who have a knowledge and appreciation of old porcelain and pottery. But few are in a position to write about it. Many do, it is true; but unprofessional research is a vocation which is not possible for most people even after the age of retirement; and public bodies can hardly be expected to help…[it is] difficult to imagine serious encouragement being given to those arts of appreciation and connoisseurship without which any artistic subject is empty and meaningless, but which are too intangible, too difficult to assess, by the business standards that are increasingly invading cultural subjects. “Am I to understand we are paying Mr Smith this annual sum for – er – let me see – cultivating the appreciation of old China? Can this Faculty really afford a Reader in Connoisseurship?”’

P.J. Donnelly (1969)

On blanc de Chine from Dehua:

‘The slenderness of the evidence on which judgement has to be formed comes rather as a shock…connoisseurship and aesthetic judgements find full play and are often right.’

‘(Blanc de Chine) depends for its appeal solely upon beauty of form and material. It has held this appeal longer than any other porcelain, even Chinese porcelain, having been produced for at least four centuries virtually without change…a steady stream of white monochrome pieces…preserving always an air of craftsmanship and frequently of distinction.’

‘The ware made an instant appeal on its arrival in Europe…Certain it is that the translucent white wares of Chingtechen appear cold by comparison.’

‘Blanc de Chine is unsurpassed amongst porcelain and often unrivalled…At its best, that is, for it will not be supposed that every piece of Tehua porcelain is of the finest…there is bound to be much that is uninspired and pedestrian.’

Of the famous Fisherman mark:

‘According to my friend Prof. Kikutaro Saito…it should be taken to mean, (the power of his virtue) influences all, (even) fishermen, though it is not clear why these honest folk should be singled out for invidious mention. Perhaps they were thought thick-headed.’

‘The kiln enjoyed no imperial patronage, and aped none; not here the practice of the private kilns of Chingtechen of using the nien hao as a means of enabling their customer to “keep up with the Joneses”.’

Sir Harry Garner (1891-1977), writing on blue and white porcelain

‘It was not until the 1930s that the transition wares began to be appreciated, largely as a result of the activities of a small group of English collectors who were attracted by the fine quality of the porcelain, the beautiful violet-blue of the decoration and above all by the splendid brushwork, which seems to reflect the spirit of the landscape painting of the period.’

‘The tendency of most collectors to concentrate on pieces of the finest quality gives a distorted picture of blue and white in the Ming dynasty and a closer study of the less sophisticated, but often more lively export wares will provide a much needed corrective.’

‘Oriental blue and white, particularly that made in China, has had during the whole period of its development a unique quality which has never been approached in any other blue and white porcelain.’

‘The K’ang Hsi blue and white reached a technical excellence that has never been surpassed.’

‘The Yung Cheng copies of blue and white, as well as of many other types of Sung and Ming porcelain, are probably the most skilful in the whole field of Chinese ceramics.’

‘The decline in standards, started in the reign of Ch’ien Lung, continued rapidly in subsequent reigns…and it is not surprising that the popularity of blue and white, now so obviously inferior to the early wares, declined.’

Loss of vigour, following the fourteenth century, through Ming and Qing ‘mainly occurs in the porcelain made in the Imperial potteries. There was a continual renewal of vigour in the non-Imperial porcelain.’

‘In the battle of wits between himself and the copyist [including fakers], the student can be certain that there is some weakness in the copyist’s armour, if only he can find it.’

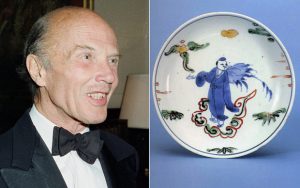

Gerald Reitlinger (1900- 1978)

‘No nation except the Chinese has exceeded the Roman passion for copies of the same original, endlessly repeated over the centuries. Strange to say, the Romans developed this habit through excessive intellectual snobbery and not through lack of it.’

‘The Roman world could only found a personality cult on the distant past…the art of the small Greek city states had survived on too small a scale to make antiquarian collecting a practicable proposition. The result of this was to reduce collecting to a cult for extremely rich and costly contemporary, or near-contemporary, craftsmanship.’

Regarding porcelain reign marks and dating (1881):

‘Everyone was now in such a muddle that there was a sort of gentleman’s agreement not to talk about it any more.’

‘In late eighteenth-century China. This was the time when the Emperor Chien-Lung (1736- 1795) was buying up pieces in the medieval tradition, which were sold to him as genuine antiques. Till the present (20th) century this was the only ground on which tastes of Europe and the austere taste of the Chinese official classes met.’

‘In 1870s nascent English aestheticism expressed itself in a taste, not for monochromes, but for “blue hawthorn” jars.’

‘The cluttering up of the English middle-class home with flatulent mass-production of India and Japan began in the 1860s. Its spread was inevitable…after two centuries of familiarity with a corrupted style, the public accepted profusion of ornament as the keynote of all Asiatic art, unaware that China and Japan had adopted it in the first place in order to compete for European custom.’

‘Ignorance of a country which was only rarely penetrated by foreigners may partly excuse the early nineteenth-century cult for coarse-quality “mandarin” vases…Still less can ignorance be held an excuse for the annual wholesale purchases of bazaar junk by such institutions as the Indian section of the Victoria and Albert Museum far into the present [20th] century.’

‘The censure of the early Victorian purists could not prevent the continuance of a subdued market for mere size…It had been possible to make [mandarin vases] as big as 5ft high…they were not meant for close inspection [they were] very costly to make.’ Such a size ‘was not to be found on the home market. Even in 1827 the Rockingham rhinoceros vase was far and away the largest piece of porcelain to have been made in England and it was only 44in high.’ These vases (there were two) were ‘outrageously rococo…(and possibly the most hideous objects in the universe).’ [Do they survive? Where?] [:2006: Victoria and Albert Museum: Rotherham Museum].

Until 1914 ‘even the most sumptuous Ming enamelled porcelain was regarded as technically too crude’.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century blue and white porcelain became a fashionable cult, initiated chiefly by the painter J. McNeill Whistler. The art critic of the Daily Telegraph wrote in 1895:

So all gave gifts, but the mandarin’s was the richest of them all. For months an artist had laboured in delight over the fashioning and glazing of a jar. On its vibrating ground of pellucid blue, pencilled over with reticulations of darker blue lines…

‘ – but enough of that. There had been no mandarin and no artist labouring in delight, but only an assembly-line team, one among hundreds in grimy toiling Ching-te Chen. And the jar, possibly filled with trade ginger, had gone off with a Dutch buyer’s consignment of similar jars…’

‘The strongest factor in making blue-and-white popular was that there was enough for everybody…On a small scale, the chosen pieces could make an exceedingly attractive display, but the monotony of large accumulations could be very deadly.’

A cult for famille noire porcelain occurred between 1890 and 1920, and black hawthorn jars in particular became ‘far and away the most expensive porcelain that has ever been sold’. ‘George Salting’s Bequest to the Victoria and Albert Museum ensures that his considerable portion remains permanently on view. There is no better place to study these fallen favourites.’ The 1920s saw a ‘growing number of forgeries and semi-forgeries’.

In 1913 auction catalogues ‘did not go all out for a jackpot by cataloguing learned comparisons and cross-references. Ipse dixit was quite enough’. A pair of seated figures of the Buddhist deity Vajrapani were described: ‘These figures are admittedly the greatest examples of Chinese ceramic art the world has ever seen and they have been put by a great art connoisseur on the same plane of merit as the celebrated Venus de Milo in statuary.’

Philip Rawson (1971)

‘Functionalism assesses works of art by what each critic takes to be their success in reflecting their function…nor can it explain the imponderable appeal that one pot can exercise, rather than another very like it…Pure aestheticism, on the other hand, concentrates on the “beauty” or “expression” of a pot without regard to its function, and is equally at a loss to explain the whole nature of humanity’s pottery, which is unequivocally utilitarian whilst also being expressive.’