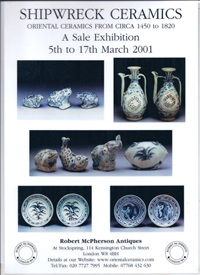

Shipwreck Ceramics

INTRODUCTION

Antiques, by their very nature, have a long history. It therefore follows that the standard of care with which they have been treated over such an extended period may well have varied a great deal. During times of peace, for instance, good care may have been taken of them, but during periods of war, it is likely they will have suffered neglect, or worse. Furthermore, succeeding generations may not necessarily have placed the same value upon the objects. Finally, this complex journey leading to the present day is rarely recorded and in this case, it is no longer possible to place the objects in their historical context.

In total contrast, in the case of objects retrieved from shipwrecks, it is frequently possible to trace their history from the potter’s wheel, to the packing of the objects, and ending with their tragic final resting place on the ocean floor.

It is sometimes possible to establish the date upon which catastrophe struck the ship, still laden with its cargo, as well as the name of the Captain, even the last thoughts he noted in the ship’s log. Often, the ship together with its cargo is found on the very spot it sank all those years ago, thus perfectly preserved in its historical context. This provides an unusual opportunity of finding a large collection of export objects, all of the same origin and all manufactured by a small number of potters. Everyday items used by the crew during their voyage are usually found among them. Frequently objects come to light that have never before been recorded.What survives of the cargo gives us an incomplete picture. Spices, It is never possible to predict what exactly will be found on a shipwreck. It is therefore hard to imagine the thrill the diver must experience as he first touches these items, which have lain for so long, undisturbed, on the sea bed, as all the while history has continued to unfold in the world far above.

- SHIPWRECKS AND THEIR CARGOES

- DATING A WRECK AND ITS CERAMICS

- THE HOI AN HOARD - Vietnamese c. 1450-1500

- THE HATCHER CARGO - Chinese c. 1643

- THE VUNG TAU CARGO – Chinese c. 1690-1700

- THE CA MAU CARGO, YONGZHENG 1723 – 1735

- THE NANKING CARGO – Chinese, Qianlong c.1752

- DIANA CARGO – Chinese 1817

- FAKES

- RESTORATION

- TODAY'S MARKET

- VIDEO 'Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia' by Regina Krahl

SHIPWRECKS AND THEIR CARGOES

From a modern perspective, it is not easy fully to understand the terrible loss in terms of money, valuable resources and lives that the sinking of a single ship would cause. Each journey represented a very important financial commitment to the merchants involved. In a world without insurance and without rescue services, each journey was an all-or-nothing matter. If a ship sank, there would be few survivors and the remains of the passengers and crew, and some of their personal belongings together with an immensely valuable but now ruined cargo, would all be lying at the bottom of the sea.

What does survive of the cargo gives us an incomplete picture. Spices, silks, dyes and tea were often far more important than the ceramic element of the cargo but being of organic matter, only small, degraded traces remain. However, even these can be of use to an archaeologist. In the case of the 15th century Hoi An Hoard for example, traces of a certain fruit were found, which only ripens in that part of the world in a specific period during the early autumn. From this it was possible to conclude that the ship had left rather late in the season and it was therefore conjectured that bad weather might well have been the cause of the disaster.

Cargoes were densely packed. Every inch of storage space was used. Tiny vases from the Hoi An Hoard were found packed within larger jars. Bowls were tightly packed to form rings, the centres of which were filled with more items. Even in the case of early wrecks, the size of the ceramic cargo can be staggering. A quarter of a million pieces were recorded from the wreck of the Hoi An.

DATING A WRECK AND ITS CERAMICS

Archaeology naturally plays a vital role in gathering clues to the understanding and dating of the objects recovered and in ensuring that the precious historical context is not lost.

With the development of new techniques in deep-sea diving and underwater archaeology, it is now possible to reach many previously inaccessible wrecks. New information of great importance can be learned from each wreck. Many new types and groups of ceramics have been discovered. Each time a wreck is correctly dated, valuable material is revealed, against which existing pieces can be compared and dated. In order to be able to do this, of course, it is critically important that the dating process be totally and utterly reliable. The greater the skill of the archaeologist, the greater is the likelihood of obtaining a sound dating. If any evidence at all emerges during unskilled salvage operations, it is a matter of sheer luck.

The work of dating a wreck depends on many factors and is not always straightforward. It is possible to date some wrecks, particularly in the case of later Western ships, by primary source material. The Geldermalsen which sank in 1752 (and is now referred to as the Nanking Cargo) was a registered Dutch ship and her complete and accurate records still exist today. Yet even in a case like this, other factors can complicate the identification of the cargo. For instance, over time, more than one ship may come to grief on the same dangerous outcrop of rocks, thus contaminating historical evidence on the ocean floor.

Frequently it is evidence within the wreck which provides the only material on which to base judgement as to date and origin. Coins may be found (bearing a date) and an invaluable “not before” date can therefore at least be established. Or, by a stroke of good fortune, an object in the cargo itself may be inscribed with a date! A case in point is the important jar cover retrieved from the Hatcher Cargo. The design, painting, style and quality of porcelain cover were all found to be consistent with other porcelain in the cargo. The jar cover bore the date of spring 1643, which thus neatly provided the time of the sinking of the Hatcher.

In another example from the Hatcher Cargo, dishes were found decorated with stylised serpents. They matched an item that can be dated to 1644-1645 belonging to the Percival David Foundation. This is an example of how comparing pieces from a wreck to existing pieces can provide another method of dating. Great care however has to be taken to satisfy several criteria: historical records, finds from the shipwreck and existing pieces all need to be cross-referenced. It would be most unwise to use only one method.

It has sometimes been claimed that ships used to carry “antique” ceramics within their cargo. It has been said that these smaller groups of old and maybe more highly valued ceramics were shipped within the main bulk of “new” ceramics. However, it is my belief that these “antiques” do not exist in groups. It is not unusual to find objects ascribed to a different period within a cargo.

Let us take for example, the small models of boys portrayed wearing blue aprons and seated with arms and legs outstretched. A number of these were recovered from the Nanking Cargo (1752). This fitted the dating theory well, as the group had always been attributed to the mid 18th century. The same figures appear also to have been found on an unpublished wreck from about 1730 – 1740. By comparing them closely, it can be seen that the 1730 – 1740 figures do indeed relate to those on the 1752 Nanking Cargo.

When similar models were discovered on the Tek Sing (1822) it was assumed by some that they were mid-18th century “antiques” on board a 19th century ship. However , after closer study, slight differences were found in the large group of 1822 Tek Sing figures. They are not “antiques” at all, but simply later examples of an enduringly popular model.

In my opinion we need to accept that traditional dating methods may occasionally result in mistakes being made. Our interpretation should be based solely on the clues from the cargoes themselves. It is essential to form any conclusions on the most careful study of the evidence available. Otherwise the evidence can appear confusing or even in some cases contradictory.

THE HOI AN HOARD – Vietnamese c. 1450-1500

The Hoi An Hoard, as has been the case with several other wrecks, was not found by archaeologists nor even by historians, but by fishermen, though happily not excavated by them. It became in fact the only commercial underwater site to have been excavated in a correct archaeological manner. It is one of the earliest cargoes (dated c. 1450-1500) to have come on to the market and to my mind is the most interesting and important of them all. Moreover, it is the only large Vietnamese cargo to have been discovered. A partnership was formed, to take charge of this landmark excavation, between the Vietnamese Government and M.A.R.E., the Maritime Archaeological Research Unit of the University of Oxford, under the Directorship of Mensun Bound, Triton Senior Research Fellow, Saint Peter’s College, Oxford.

Vietnamese ceramics were not treated with the importance they deserved until very recently. Several excellent new books have now been published on the subject and an exhibition of Vietnamese Blue and White has been held at the British Museum, where objects from the Hoi An Hoard featured among the exhibits. Together with the recent excavation of the kiln sites, this cargo underlines the importance and individuality of Vietnamese ceramics. I believe that the cargo in fact contains more Vietnamese ceramics of the period than exist worldwide, taking into account not only all the museums but also all the private collections. The Hoard will be a source of research for years to come.

Furthermore, due to the thoroughness of the archaeological excavation, much else of interest was recovered. Evidence of the crew’s diet was found, including the remains of berries and fish, as well as fruits which grew only late in the sailing season. Even the remains of some of the crew were retrieved together with those of their cat, and twenty rat skulls.

It has not yet been possible to establish a dating of the wreck but the timbers of the ship have been dated to c.1450 (plus or minus twenty years) and it is thought that the ship had been built quite shortly before it sank, as its timbers only showed moderate wear. Yonglo coins were found (1403-1424) and most interestingly a small (as yet I believe unpublished) amount of Chinese ceramics used by the crew was also recovered. These appear to belong to the Interregnum Period of the mid 15th century.

Researchers are still studying the evidence and with work on the kiln site still ongoing, it is hoped that an accurate date will soon be agreed upon. At present, there appear to be two schools of thought. One dates the wreck to c. 1450-1470 and the other to c. 1480-1520. It would seem that a 15th century date is almost certain.

The ceramics, a heavy hard pottery of rather open texture, were made near Chu Dou, six kilometres from Hai Dong, this having been the largest centre of ceramic production in medieval Vietnam. The quality of the ceramics onboard ranged from crude everyday vessels to exquisite pieces decorated with great skill. The style of the decoration was very free and appears often to have been painted at speed using a very wet brush. Individual lines of the decoration have a visible starting and finishing point. The exact spot where the artist first touched the surface of the ceramic object with his brush can be identified and then where he removed it. I say “he” but a most important jar in the Topkapi Saray Museum in Istanbul is signed and dated by a female artist. Men, women and many children were all employed in ceramic production in Vietnam.

Many of the form s and designs were based on nature and included water droppers in the shape of fish, frogs, tortoises, peaches and even elephants. The designs were also based on the natural world so familiar to these Vietnamese potters and included birds in flight or in trees, fish swimming among water plants, extensive misty landscapes or simply a small flowering branch.

Most of the cargo was destined for utilitarian use, and contained a huge number of dishes and bowls for everyday meals. The remainder were luxury items of a plastic form and ranged from water droppers to ewers, which had moulded reticulated panels and would originally have been gilded. Other luxury items discovered included the “Parrot Cups”. These wonderful objects, unique to the wreck, were in a variety of forms and styles of painting. The basic design always consisted of a parrot curled around a hollowed out peach. In some cases the bird’s head reached inside the fruit, in others the head followed the curve of the edge. Some were decorated in blue and white and in some cases polychrome enamel had been added to the decoration.

Although they have been referred to speculatively as “cups”, the function of these beautiful vessels remains uncertain. As the parrot represents female beauty and the peach represents longevity it is in d eed possible that they were to be used for cosmetics. There are many forms of containers for cosmetics in Oriental ceramics. Boxes, often with the interior fitting in the shape of lotus flowers to take different cosmetic products or colours are known as early as the Song Dynasty (968-1279) in China for instance. Comparatively few of these unique Parrot and Peach cosmetic cups, if that is what they are, were recovered from the wreck, reinforcing the supposition that they were indeed luxury goods.

A vast array of small boxes with covers was also recorded. The variation in form, size and quality is extraordinary. A few larger boxes were found, some bearing beautifully executed landscape decoration on the lids. In some cases, this decoration extended from the sides up to the lids. In other cases, a circle had been painted over the join between the lid and the bottom of the box, thus ensuring the correct lid would be fitted to the correct box.

Objects destined for scholars were also found, including many water droppers that would have been used for making writing-ink. They were more than functional objects, made in two-piece moulds. Some were made in the form of an animal or a fish. Toads and other creatures connected with water seem to have been popular. These droppers, which had a hole on their back and another hole forming the mouth, were used to add water to dry ink cakes on a grinding stone. The ink made in this manner would then have to have been used immediately.

Very similar objects are in the British Museum and are also described as water droppers, even though they only have one hole on the back. I feel these do not function as water droppers, but I am unable to find an alternative use for them. A few might be water pots and used to store small amounts of water to wet a brush, but the apertures are very small in some cases for this purpose. There were other vessels retrieved from the wreck whose function has not been identified.

There were a dozen Aubergine shaped containers, which were unique to the wreck and we were fortunate enough to be able to purchase all twelve of them from the original sale. In the side of each is a perfect round hole but it appears impossible either to introduce or to extract anything at all through this aperture.

As previously explained, the vast majority of the 250,000 pieces recovered were utilitarian objects. The dishes were simply shaped and thickly potted, as they were made in moulds. This had the benefit of making them more durable. It also made it possible to produce a large number easily and at great speed, thus reducing the cost of production, as it eliminated the need for an expert potter.

The dishes were fired face-to-face without individual saggers making it possible to fit more dishes in the kiln, another clever cost-saving idea. The glaze, in common with all existing Vietnamese dishes, was wiped clear of the rims of the dishes in order to prevent them from sticking together.

Tragically, this wonderful and varied cargo never reached its destination. It sank in the dangerous Dragon Sea off the coast of Vietnam, near Hoi An.

THE HATCHER CARGO – Chinese c.1643

The Hatcher Cargo, the first to come on to the market (March 1984), is of great historical interest. It is most regrettable that no details of the wreck site were recorded. The salvage operation was purely and simply a commercial affair. It is probable that the ship was a Chinese junk, containing items that were destined for both the local South East Asian market and the European (in all likelihood the Dutch) market. Accurate dating has presented a problem as archaeologists had no hand in excavating the site. However, as mentioned in the Introduction, a jar with a lid bearing the date “spring 1643” was found and dishes were also discovered decorated w ith sea serpent that matched an example, dated 1644 – 1645, belonging to the Percival David Foundation.

Of the 25,000 pieces recovered, most were Blue and White from Jingdezhen. As is the case with all the other cargoes discussed, these varied greatly in quality. The merchants knew their markets: cheap, poorly decorated wares for every day use were packed along side fine, translucent, well-painted pieces destined for the wealthy in South-East Asia and the Dutch upper classes. Beautiful reticulated cups, with sides that were intricately cut to leave a delicate trellis of porcelain, contrasted with the thickly potted Swatow ware. Although some have a simple rustic charm, they are generally crude, badly made, sometimes even unattractive.

The cargo was due to be trans-shipped. Some of it was destined for the local South-East Asian market, and included bird feeders, cricket cages and pickle dishes. There were also many items that had been made for the West, including Western shapes. The Dutch East India Company (the V.O.C.) had been sending wooden shapes out to China for copying purposes from the 1630s. Beer mugs, kettles, large dishes, bowls and jars were all specifically made for the Dutch market.

The cargo also contained some of the last pieces to be exported in the Kraak style (a style where the decoration is divided into panels). It is interesting to compare objects from this cargo with the many pieces of Kraakware that appear in Dutch still life painting of the period. In some cases, an exact match has actually been found between an object from the Hatcher cargo and a ceramic object in a painting. It is conceivable that they were both even made by the same person.

These ceramics were produced at a time in Chinese history when central power was decaying. It was a time of upheaval and scant historical evidence remains today regarding ceramic production during this amorphous period, which has been referred to as the Transitional Period, so difficult has it been to ascribe accurate dates to the ceramics of the very end of the Ming (1644) and early Qing dynasties. In 1644, the Ming Dynasty fell. Civil war raged for many years. The ceramics from the next cargo to be discussed, the Vung Tau Cargo, were produced at the end of this period of civil unrest. The kilns had been rebuilt and the result was a dramatic increase in ceramic production.

THE VUNG TAU CARGO – Chinese c. 1690-1700

The Vung Tau wreck was discovered by Vietnamese fishermen and turned into a salvage operation. Some archaeological information was however saved. It was discovered for example that some of the ship’s timbers were badly charred, suggesting that the ship had met with one of the most feared problems that can arise at sea: fire.

The Chinese junk was en route to the town of Batavia (present day Jakarta) in Indonesia. Batavia was the centre for the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.). The V.O.C. was the first Dutch company to be funded by shareholders. It began as an attempt to unify the various Dutch companies trading in the East, that were competing against each other. By the late 17th century it had become a massive operation. Central control was supposed to come from Amsterdam, with Batavia and the other bases taking a secondary role. Given the difficult and slow communications and the need to deal with the reality of local practicalities as and when necessary, Batavia tended in practice to adapt or to modify the instructions that had been issued from Amsterdam.

Batavia was a large and busy town, built following a Dutch model, complete with a castle, administrative buildings, law courts, churches and a canal. The complex trading relationship the Dutch had with Asia was too involved to describe here in any detail but it is interesting simply to note that Batavia was the most important trans-shipment centre the Dutch had. Goods would arrive from Holland, be traded and oriental goods would be sent back to Holland.

About 70% of the Vung Tau cargo was to have been trans-shipped to Holland on an East Indiaman vessel from Batavia. But the Vung Tau junk never reached the Dutch trans-shipment centre.

The great interest in Chinese porcelain in England had been prompted by the arrival of Queen Mary from Holland, and the enthusiasm she brought with her for Chinese Blue and White porcelain. Her palaces in Holland, and later in this country, were filled with the Kangxi Blue and White porcelain that she loved so much.

Unlike the individual pieces of Blue and White from the period of the Hatcher Cargo (c.1643), the Kangxi porcelain objects from the Vung Tau Cargo were mostly to have been displayed as a collection. The pieces had been made as sets, to be arranged together for impact, and displayed on gilt stands and brackets made for the purpose. These were used to create a rich glittering effect together with garnitures of vases, miniature vases, dishes, and cups and saucers reaching from floor to ceiling. These massed baroque displays have long since been removed from many palaces. However, in Kensington Palace, as part of its restoration, the curators are attempting to replace some of the Kangxi porcelain. Part of the display will include items from the Vung Tau Cargo. Perhaps destined originally for a royal palace, it could be said that the porcelain is finally arriving at its destination – albeit three hundred years or so late!

Although some of this cargo might indeed have been intended for a palace, it represented a typical cargo produced for the flourishing Dutch middle and upper class clientèle. A use would have been found too for some of the less purely luxurious and more functional items. Tea, coffee and hot chocolate – newly fashionable beverages – were luxuries that only the wealthy could afford. All three were both exotic and expensive and thus fine porcelain, instead of native European pottery was needed. Many different shapes of blue and white porcelain cups, some with covers, and saucers were i ncluded in the cargo.

Several rare Kangxi porcelain items were among the cargo including tazza, spice dishes and most importantly Kangxi porcelain vases decorated with the Dutch Canal Houses pattern. These vases are unique, decorated with rather sketchy views of what are clearly Dutch houses. Dr. Christian Jorg (author of the excellent “Porcelain from the Vung Tau Wreck”, see Section “Books about Shipwreck Ceramics”) speculates that these vases must have been specifically ordered for wealthy Dutch clients.

Finally, the Blanc de Chine (white porcelain from Dehua, Fujian Province) has not yet been mentioned. A few Blanc de Chine porcelain figures o f Guanyin were found, though the bulk of the Blanc de Chine porcelain consisted of wine cups, tea bowls, saucers, bowls and dishes. I believe it is probable that these had been made for the South East Asian market, as was the case with various other ceramics. However, had a Dutch merchant discovered them at an appropriate price, he might well have been inclined to buy them for the Western market.

THE CA MAU CARGO, YONGZHENG 1723 – 1735

Dating is often one of the most contentious issues when researching a shipwreck site. In this case, an approximate date is not difficult to ascertain. Coins that date from the Kangxi Period (1662-1722) were recovered from the wreck. Chinese coins, like their Western counterparts, were often in circulation over a long period of time, therefore these coins do not necessarily give a Kangxi date for the wreck, but do provide a `not before` date. Most importantly of all, a group of wine cups were recovered from this shipwreck, bearing a four-character Yongzheng mark, indicating that they were made during the Emperor Yongzheng`s reign, which lasted from 1723 to 1735.

Yongzheng Porcelain Brush Rest, Ca Mau Cargo 1723-1735. Robert McPherson Antiques – 25306.

The style of the potting, glazing and painting of these cups are all consistent with other known pieces from the Yongzheng period. Other porcelain removed from the wreck is also consistent in style, which suggests that all the porcelain was made during the same period. For a number of years now, I have suspected that a considerable amount of porcelain ascribed to the reign of the Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) was in fact made during the shorter reign of his son Yongzheng (1722-1735). Aft er studying the two styles over a long period of time, it has become apparent to me that many pieces of Yongzheng porcelain previously had been wrongly identified as belonging to the better-known period of Kangxi. The Ca Mau wreck, I believe, helps re-establish the importance of the large output of Chinese export porcelain during the Yongzheng period. It must be remembered, however, that a dynastic change did not necessarily influence the styles of Chinese export porcelain. The first year of Yongzheng by no means saw a sudden shift in ceramic styles. The Chinese porcelain export trade was a commercial enterprise and popular patterns were used for as long as demand continued. Change as well as technical innovation occurred but it was the changing demands of customers that brought about a change in style from the late Kangxi period to the Yongzheng Period, indeed styles always change because producers try to understand what will sell at any given moment. These changes are evident in the ceramics recovered from the Ca Mau cargo.

The use of `Pencilled` decoration is an example. The decoration is painted in outline only, without the use of tonal washes. The style is found in some late Kangxi porcelain but it reached maturity during the Yongzheng period. The profile of some of the tea bowls became less rounded, and the manner of painting faces and hair also changed during this period. All these elements are to be found in the porcelain recovered from the shipwreck. The cargo forms a most useful historical bridge between the Kangxi porcelain of the Vung Tau Cargo produced during the 1690`s and the Qianlong porcelain produced in 1750-1751, recovered from the wreck of the Geldermalsen, now known as the Nanking Cargo.

The ceramics from the shipwreck were sold in Amsterdam, the catalogue had a strange title : Made in Imperial China, 76,000 Pieces of Chinese Export Porcelain from the Ca Mau Shipwreck, Circa 1725. (Sotheby’s Amsterdam, 29,30 & 31 January 2007. 274 pages. 1208 lots.)

THE NANKING CARGO – Chinese, Qianlong c.1752

The contemporary records of the Dutch East India Company, the V.O.C., include a great deal of information about the so-called Nanking Cargo. Dr Jorg was responsible for carrying out much of the research. The wreck of the Geldermalsen has been referred to as the Nanking Cargo ever since the original auction that took place in April and May 1986. The reason for this appellation was that in the eighteenth century, Blue and White Chinese porcelain of the 1760s was advertised either as Nanking or Nankeen China. Vast amounts of this porcelain, destined for the West, were now being produced for the new middle classes, and not only for the very wealthy, as had been the case in earlier periods, for example as seen in the Hatcher Cargo of c.1643.

The Geldermalsen, built in 1746, was one of the newest and finest of the Dutch East Indiamen. She measured 150 feet long and 42 feet wide. Captain Jan Morel, aged thirty-three, and his large crew of Dutch sailors, along with sixteen Englishmen, set sail for Holland from Canton. However disaster struck and on Monday January 3rd 1752 the Geldermalsen hit a reef and sank. Eight days later the exhausted survivors managed to reach Batavia by means of a barge and long boat.

A Nanking Cargo Porcelain Saucer Dish. Robert McPherson Antiques – 25183.

The ship had been carrying an extremely valuable cargo of tea, Chinese silks and textiles, none of which have survived. The vast cargo of Chinese porcelain as well as of gold did survive. It is interesting to note that the ceramics only represented five per cent of the total value of the original cargo. There is no doubt that tea had been the principal reason for the journey. The Geldermalsen disaster represented a loss of 900.000 guilders for the Dutch East India Company. It is worth noting that as a result of the loss of the ship, the porcelain from the cargo of her sister ship, the Amstelveen, subsequently achieved far higher sale prices than it would otherwise have done, having become the only shipment of porcelain to reach Holland that year.

By the mid 18th century, Chinese export porcelain shapes had become more standardized, and patterns were designed to appeal to European taste. Far fewer items were being produced purely for decorative purposes. Changing fashion and social change were both responsible. As so often occurs, the two were inextricably linked. The middle classes were expanding, and as a result merchants, shopkeepers and others had more money to spend. Huge services were ordered for the newly fashionable formal dinner parties. One hundred and seventy-one services were included in this cargo. Every item needed for the table was produced in Chinese porcelain, so the services sometimes contained between one hundred and fifty and three hundred pieces. The drinking of tea and coffee was still very popular with the expanding middle class, but the baroque displays of the Vung Tau period (Kangxi c.1690 – 1700) were no longer in fashion.

A large amount of the porcelain was decorated with landscapes either in Blue and White or Imari (blue and white with over-glaze of red and gold), although Blue and White formed the major part of the cargo. Unfortunately the Imari over-glaze decoration has been badly discoloured by the movement of the sea.

The Nanking Cargo caught and indeed continues to catch the public’s imagination, even though the ceramic historian was not able to learn as much from this cargo as from many of the others. This was due in part to the plentiful historical evidence already available for this later period. One reason that this Cargo of porcelain fascinated the public may well be that the ship’s original records were found, containing an extremely detailed account of both the ship itself and its crew. For whatever reason, this cargo remains by far the most famous of all the shipwreck cargoes. The Nanking Cargo appears in the news and in television programmes. Books are devoted to the subject. It is the cargo about which we ourselves receive the most enquiries.

DIANA CARGO – Chinese 1817

The ship was on course for Madras, but soon met with disaster. Survivors were able to recount the terrible events. It seems that the Diana sank in the Malacca Straits at about half past ten at night on March 4th 1817.

The ceramics from the cargo give a snap shot of the trade of that time, as all cargoes do, and they were mostly found to be of poor quality. A few decorative pieces were nevertheless found. By this time, European, especially English, factories were using modern methods to produce ceramics and were able to undercut Chinese production. Economy was the essence of trade during this post-Napoleonic period.

FAKES

Adding a note of caution about fakes may seem surprising, as many of these cargoes have only been on the market for a relatively short time. In fact the first Vung Tau Cargo fakes came on to the market several years ago, although they were rather crudely potted and much too heavy.

However, I was recently shown some fakes that were quite well potted. The glaze had even been lightly etched with acid to imitate the saline and physical deterioration that occurs on genuine shipwreck ceramics. It would clearly be inappropriate to provide more details here. Suffice it to say that any person familiar with originals would have realized they were fakes.

I was vetting an antiques fair in 2007 when I came across a group of blue and white porcelain apparently from the Vung Tau Cargo. They looked very convincing, they even had barnacles on them. The barnacles had clearly grown on the porcelain but they were still fakes !

Fakes – Beware !

We have been able to acquire a few fake wares purporting to be from the Hoi An Hoard. These are displayed in the shop, side by side with the genuine articles to draw attention to the differences in quality.

It is advisable, as when acquiring any antique, to buy only from a reputable dealer or at auction and to obtain a receipt that guarantees authenticity as well as the condition of the piece. I am always willing to give a without prejudice opinion, if one is needed.

RESTORATION

As most shipwreck ceramics come from the Far East, it is important to be aware that even the cheapest pieces may already have been restored, given the much lower labour costs there than in the West.

A large number of the pieces of a more complex shape retrieved from the Vung Tau Cargo were in very poor condition and were restored at the time. The handles of mustard pots and teapots, for example, were sometimes even completely replaced.

The most difficult restoration to detect is once again associated with the Vung Tau Cargo. These are referred to as “marriages” in the antique business. Parts of two genuine pieces are removed and then grafted together. I have for example seen a base that had been grafted. On one occasion the join was so good, I myself missed one of these repairs. It was not until after I had bought the item, and had examined it again very closely that I realised I could just make out the fine line of a graft…

Once again it is important to stress how absolutely essential it is for the customer to obtain a detailed invoice, which should include information about the condition of the item.

TODAY’S MARKET

For the last twenty years, I have been following the market in shipwreck ceramics with increasing interest. As in all markets there are highs and lows depending on fashion and availability. In this case there has been another factor and that is publicity. Christie’s Auctioneers launched a huge advertising campaign to promote the sale of the Nanking Cargo. Shipwreck ceramics became the “must have” for ceramic collectors.

The sale of the Vung Tau Cargo was subsequently launched by Christie’s on the back of the success of the Nanking Cargo but this time there were differences: not only were fewer pieces available, they were also more expensive. Dealers therefore competed with each other, not wanting to be left out of another cargo phenomenon. As a result, prices rose. What had not been foreseen was that customers were unwilling to spend several hundred pounds on a single vase, when they had been able to buy a cup and saucer from the Nanking Cargo for considerably less than a hundred pounds.