A Fine Shoji Hamada Tenmoku Stoneware Dish

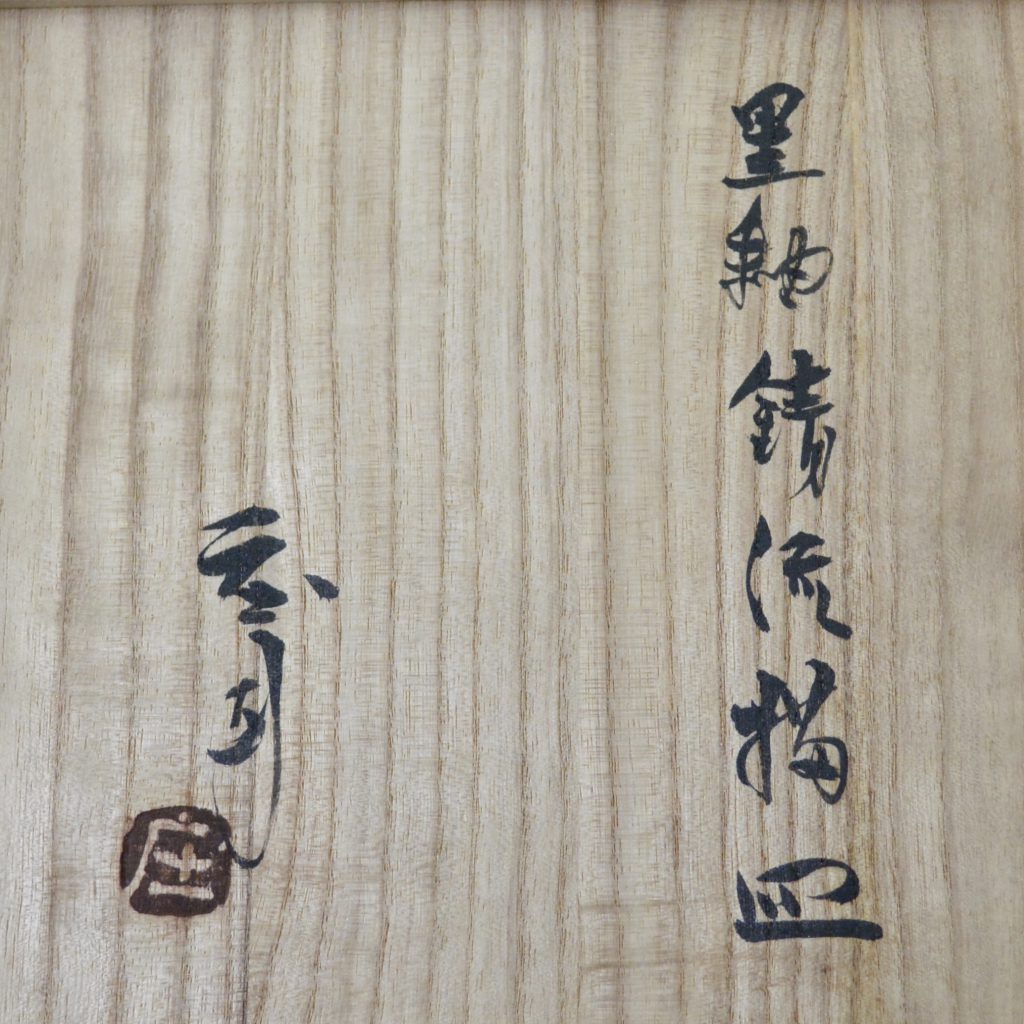

A Fine Shoji Hamada Stoneware Dish with a Black Tenmoku Glaze with a Trailed Russet Design c.1965. Hamada became a living ‘National Treasure’ in 1955 and was a master of the trailing technique using rich iron-loaded glazes and dishes such as the present example became a ‘specialities of the house’. Hamada was exposed to English slipware during his time in St. Ives during the 1920’s and this influenced his work. English slipware mirrored the Japanese Mingei tradition (folk-art) which he, among others, was instrumental in reviving in Japan. Most of Hamada’s work is not signed, he preferred to inscribe the presentation box and apply his seal-mark in the underneath of the cover. This dish comes with its inscribed paulownia wood box that has the seal-mark of Shoji Hamada.

This dish takes me back to my childhood and my introduction to ceramics as a teenager in the 1970’s. My parents took me to the Leech pottery in St. Ives which Hamada helped set up, we had some Leech pottery at home, most of which I still have. My father was particularly taken with the seductive rich black and brown glazes, as was I. The first ceramics I purchased were by Nic Harrison , they were black-glazed stoneware mugs in the Leech / Hamada tradition. Nic is still potting in Cornwall and I occasionally buy pots from him, some forty odd years later.

SOLD

- Condition

- perfect

- Size

- Diameter 27cm (10 1/2 inches)

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 25698

Information

Shoji Hamada 1894 - 1894

Shoji Hamada was one of the most influential potters of the 20th century. Hamada graduated from Tokyo Technical College in 1916 and enrolled at Kyoto Ceramics Research. During the years from 1919 to 1923, Hamada travelled extensively to learn about diverse ceramic and folk craft traditions, and built a climbing kiln in England at St Ives with Bernard Leach (1887–1979). In 1952, Hamada travelled with Soetsu Yanagi (1889–1961) and Bernard Leach throughout the United States to give ceramic demonstrations and workshops. Hamada's work was influenced by a wide variety of folk ceramics including English medieval pottery, Okinawan stoneware, and Korean pottery. His works were not merely copies of the styles he studied, but were unique products of his own creative energy. Hamada’s great respect for artisan crafts led him to draw as much as possible from folk traditions. After receiving the Tochigi Prefecture Culture Award and Minister of Education Award for Art, Hamada was designated a Living National Treasure in 1955. Thereafter, he was appointed Director of the Japan Folk Art Museum and awarded the Okinawa Times Award and Order of Culture from the Emperor. In 1961, Shoji Hamada: Collected Works was published by Asahi Shimbun. In 1973, Hamada received an honorary Doctor of Art degree from the Royal College of Art in London, England. Shoji Hamada died in 1978, four years after the completion of the Mashiko Sankokan Museum, which was built in his home. Hamada's influence on potters around the world is incalculable, and the village of Mashiko has become synonymous with Japanese folk ceramics.

A Related Shoji Hamada Stoneware Dish, Dallas Museum of Art.

The Mingei Movement

The Mingei (folk-art) movement was initiated by Yanagi Soetsu, Kawai Kanjiro, and Hamada Shoji in 1926 as an approbation of functional craftwork used by the masses in the course of daily life. At the time, the craft world was dominated by decorative pieces prized for their aesthetic value. In response, Yanagi and cohorts promoted the quotidian lifestyle implements handmade by anonymous craftsmen as mingei (“craft of the common folk”), arguing that such works have a beauty that rivals fine art, for beauty can be found in the everyday. A further pillar of the movement introduced a “new way of looking at beauty” and “aesthetic values” via the notion that crafts born from the local practices and rooted in the rhythms of the rural regions of Japan embody a utilitarian, “healthy beauty.” Their ideology was, in many ways, related to the era, marked as it was by the advance of industrialization and tandem gradual influx of mass produced products into the sanctum of daily life. Troubled by the loss of “handicraft” across Japan, the Mingei movement warned against the easy progression of modernization/Westernization. In this way, the Mingei movement served as a vehicle for the artists to pursue the question of what constituted a good life, rather than simply a life rich in material wealth.