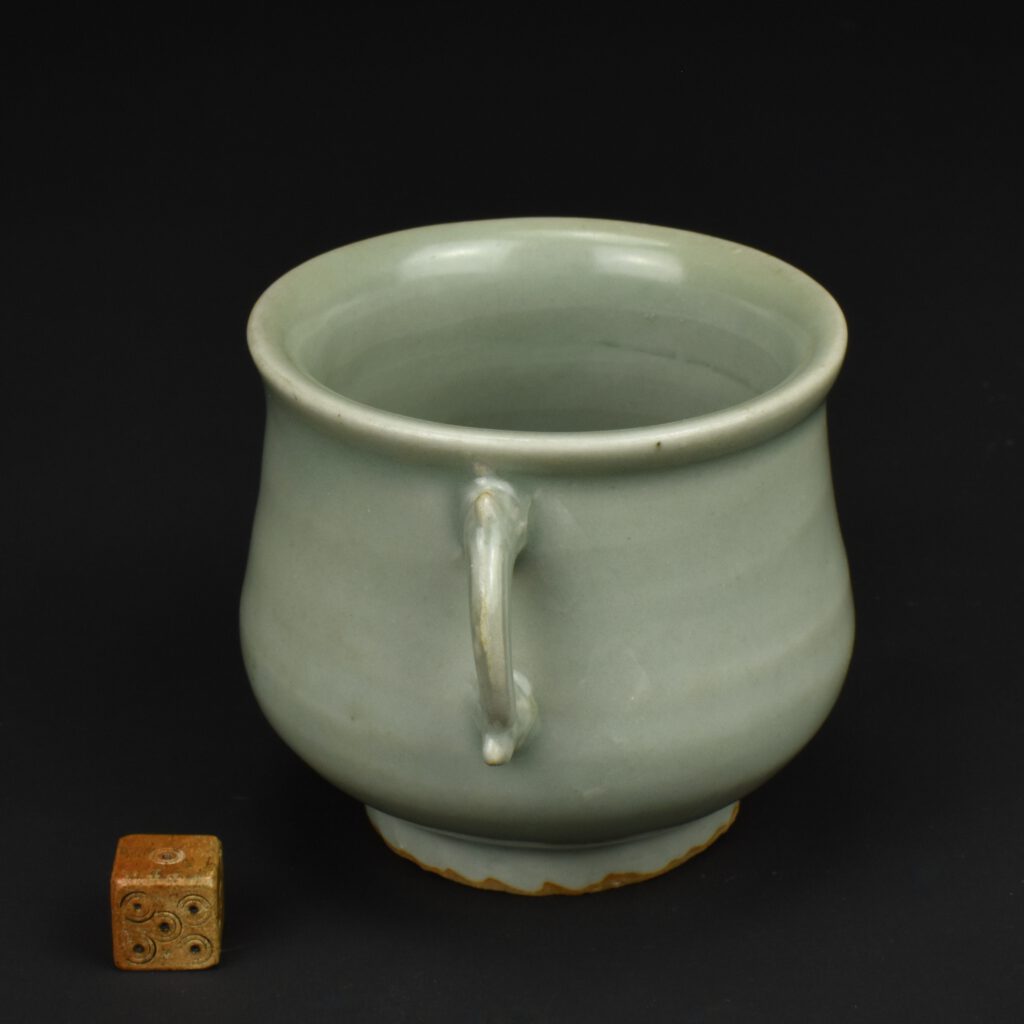

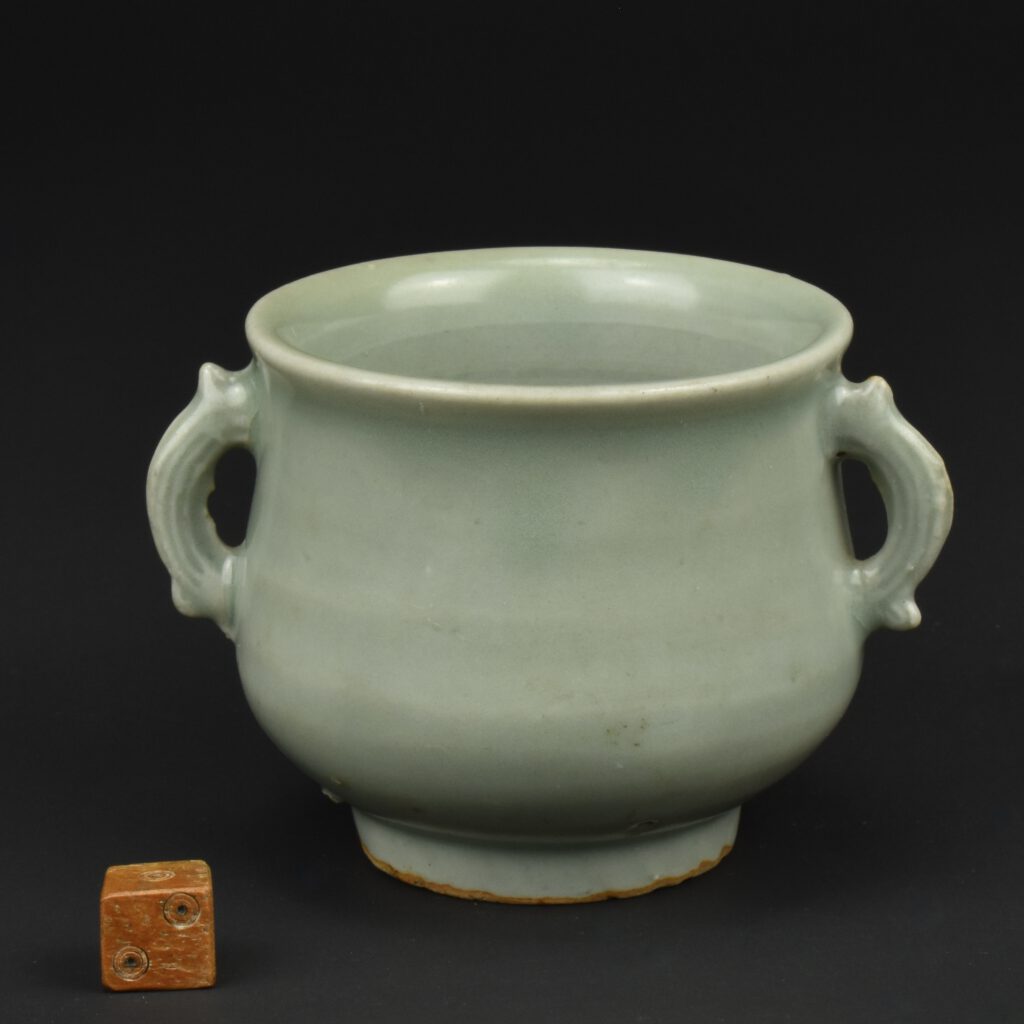

A Song or Yuan Celadon Censer

A Southern Song or Yuan Celadon Fish-Handled Censer, 12th or 13th Century, Longquan Kilns, Zhejiang Province. This small censer is based on an archaic bronze form, the body was thrown, each handle was made in two halves and lutted together. Published in an exhibition catalogue : Chinese Celadons and other related Wares in South East Asia (Compiled by the Southeast Asian Ceramic Society Singapore. Arts Orientalis Singapore 1979) page 144, plate 55. This censer was catalogued as a beaker, but it is a censer in my opinion.

Censers : Chinese censers have a long history, they are thought to have originated in the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770 – 256 B.C.). They are normally association with paying reverence to ancestors, the smoke omitted was thought to be a way for the living to communicate with the spirit of the dead. However, from early times there have been different censers for different functions including fumigation and even pest control. They also occur in many different forms. During the Western Han dynasty Western Han (206 B.C. – A.D. 8) the Boshan Xianglu universal mountain censer was developed. These bronze censors had elaborate craggy mountain peaked covers which aloud the incense smoke to waft out of naturalistically rendered holes, like so many bronze forms they were copied by potters who made lead-glazed pottery versions. The incense cones that created this smoke were made from plants, including magnolia, grasses and lovage, however early Taoists might have preferred something stronger, adapted censers for the religious and spiritual use of cannabis. Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasty ladies at court used novelty censers to fumigate new cloths, a Yuan poem includes the lines “The incense continues burning in the golden duck censor `til midnight, as court ladies keep trying on their new garments of silk and muslin”. For a Ming dynasty bird form celadon censer see sold items stock number 18026. Most Chinese censer are, however, of circular form and sit on three low feet, the interior is unglazed and left in a biscuit state. Some of the Yuan and Ming celadon censers have impressed decoration to this biscuit area. Sand was placed inside the censer and joss sticks or cones were used. Many family`s had an alter at home where rituals were performed and respect was paid to their ancestors, incense burners were an important object in this context, often forming part of an alter garniature with a pair of vases. Indeed we know from the inscription on the famous `David Temple` vases now at the British Museum, not only that they were made in the year 1351, but that there was originally a censer with them, unfortunately now lost, (for an illustration of these important Yuan vases see our `Links` section, where they are shown next to the link to the British Museum website where you can read more about them). Because of there ritual use, censers, like the missing David censer, were sometimes commissioned for a specific temple or other building. They person commissioning them sometimes had a dedicatory inscription added. For example a Dehua blue and white censer we sold many years ago. It had an inscription that mentions the name of the family who presented it, as well as the temple the piece was given to, along with a date, the twelfth year of Qianlong (1736 – 1795) equivalent to 1748. It also asks for more children and riches. China`s renewed connection with its spiritual past has meant that censers are once again being lit across the land.

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

SOLD

- Condition

- Minor cracks to the handles.

- Size

- Height 6.5 cm (2 1/2 inches).

- Provenance

- From the collection of Mr.Chang Loo Peng. The Collection of Helen Espir. R&G McPherson Antiques (stock number 15418), Nicholas de la Mare Thompson (1928-2010) Purchased at Olympia Fine art and Antiques Fair 3rd of June 2004.

- Stock number

- 26668

- References

- Published in an exhibition catalogue : Chinese Celadons and other related Wares in South East Asia (Compiled by the Southeast Asian Ceramic Society Singapore. Arts Orientalis Singapore 1979) page 144, plate 55. The catalogue mentions that it was loaned by Mr.Chang Loo Peng.