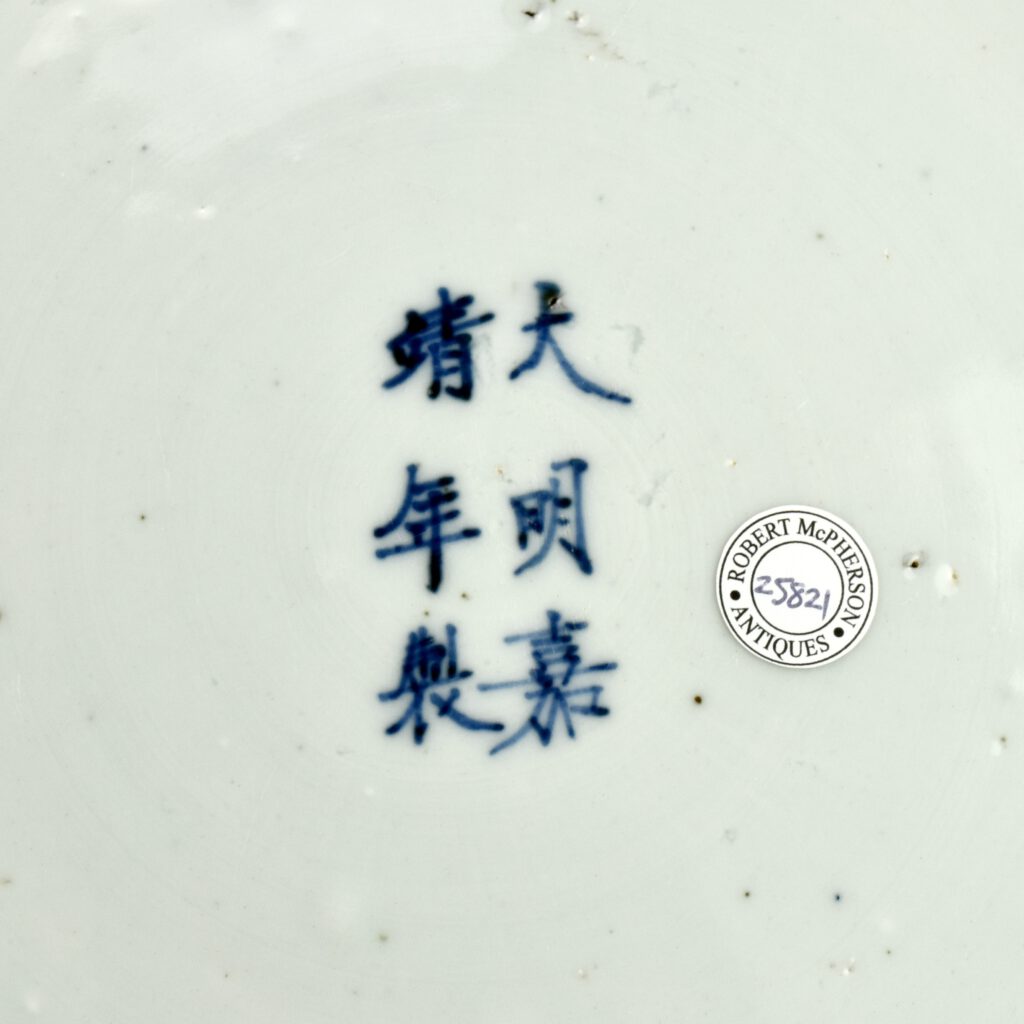

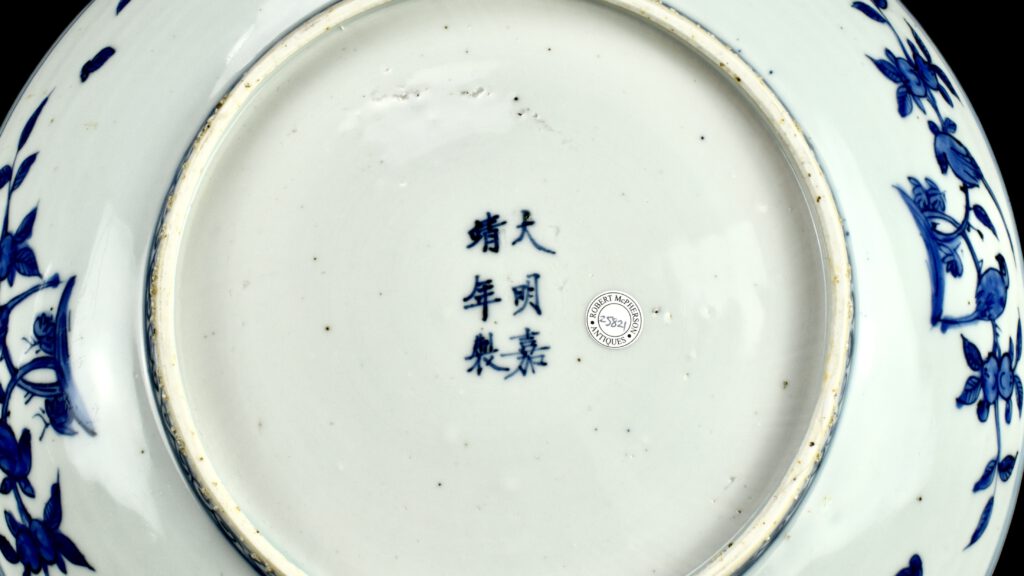

A Large Rare Jiajing Mark and Period Blue and White Imperial Porcelain Dish

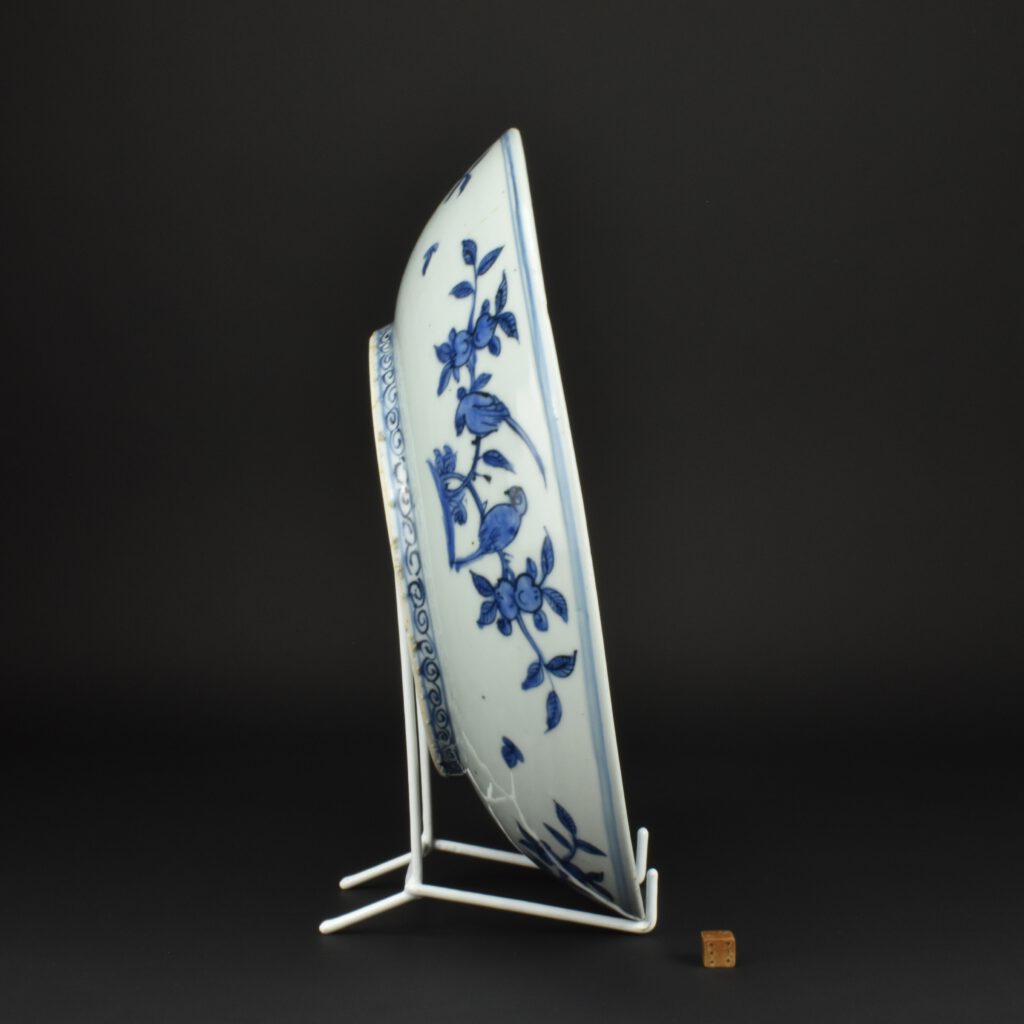

A Rare Large Jiajing Mark and Period (1522-1566) Blue and White Imperial Porcelain Dish. This large Jiajing saucer shape dish is painted with five deer, three of which are in the mid-ground, with the other two behind, partially obscured by the mound. To the upper left rocks overhang, with a dramatic waterfall and a tortoise swimming below. The rocks stretch out with a branch of pine reaching over to the right, with the moon (or sun) above, just touching the concentric circles. This double circle frame matches the outer concentric circles that are just below the rim. Large blue and white Jiajing dishes of this type are normally decorated to the cavetto, but this example is left plain. Another blue and white Jiajing mark and period dish with a very similar central design, but with an everted rim that has a border design, is in the Topkapi Saray Museum in Istanbul (see References). A Jiajing mark and period dish that is of the same shape, and design, is in the Ardebil Shrine (Chinese Porcelains From The Ardebil Shrine by John Alexander Pope. See References). The Five Deer in the center of this design have several meanings. Deer lu is a pun for road, the five roads or paths represent the five directions, north, east, south, west and center. The deer is one of the symbols of longevity, simply because it can live for a long time. The tortoise represents steadfastness, strong and slow moving. In this image the waterfall pours over the tortoise, however its unperturbed by the fast-moving water. Pine Song is often portrayed as a gnarled weather-beaten plant, again it is a symbol of longevity but it also represents nobility and venerability. This dish has been photographed in different light conditions.

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

SOLD

- Condition

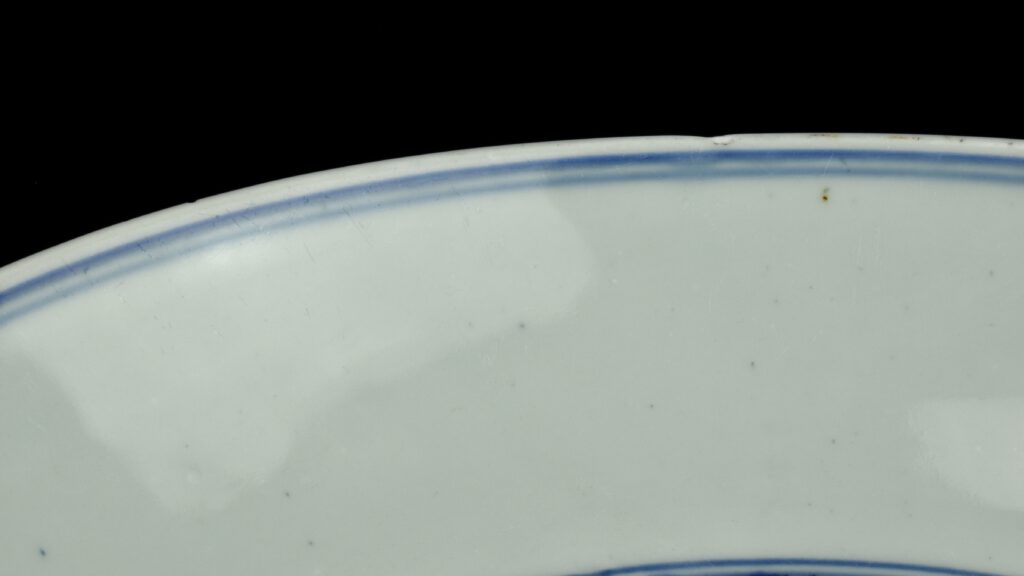

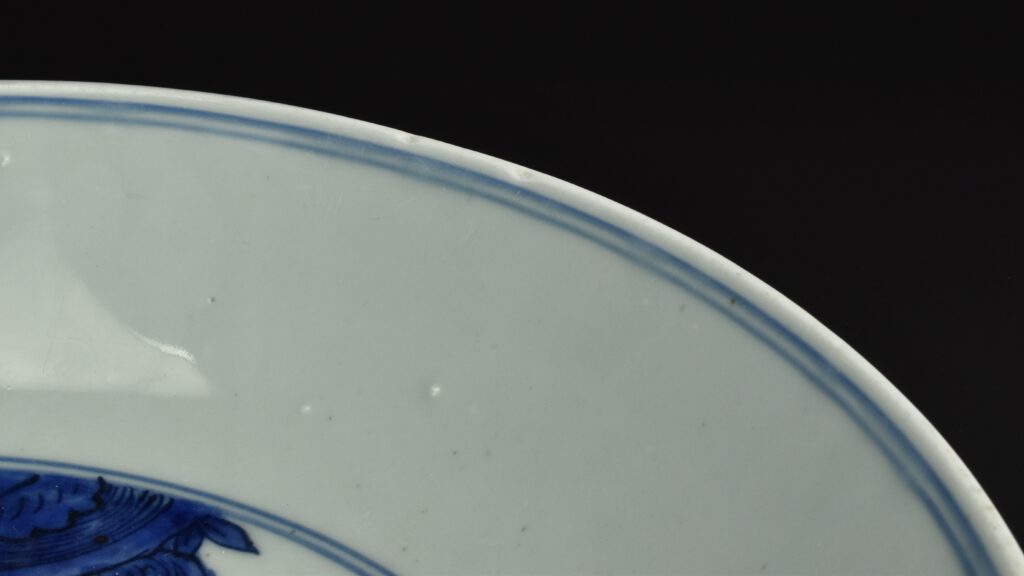

- In good condition, two small shallow rim chips slightly polished, a very small frit (see the two rectangular photographs in the Photograph Gallery below. Like many large Jiajing mark and period pieces, this dish is warped (this shows in the photographs of the back and of the dish laid flat). Minor wear and some light scratches.

- Size

- Width : 35.5 inches (14 inches). Depth : 8 cm (3.1 inches).

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 25821

- References

- For a Jiajing mark and period dish of this shape and pattern see : Chinese Porcelains From The Ardebil Shrine (John Alexander Pope, Smithsonian Institute, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington 1956. Smithsonian Publication 4231) see page 129 and plate 91. For a similar Jiajing mark and period dish with a painted everted rim see : Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istanbul, A Complete Catalogue, Volume II, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Porcelain (Regina Krahl, Published in association with the Directorate of the Topkapi Saray Museum by Sotheby`s Publications 1986) page 619, plate 882.

Information

Jiajing Imperial Blue and White Porcelain

During the Jiajing period (1522-1566) a large variety of imperial ceramics were produced, they varied from small delicate wine cups to massive fish bowls and dishes. These Ming Jiajing dishes could be as much as 80 cm across, for example a very rare unmarked yellow ground blue and white porcelain dish with a five claw dragon, from the Percival David collection, now in the British Museum : (https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_PDF-731). It was an extraordinary achievement to make such a monumental dish at that time, in her description on the British Museum website, Jessica Harrison-Hall describes the dish as "gigantic", it certainly is. It is highly unusual, not just because of its size, but also that it doesn't have a six-character Jiajing mark, despite the imperial dragon and imperial yellow ground. The kilns had to work out how to pot and fire some of the heaviest porcelain objects that had ever been produced. The fish bowls were vast and incredibly heavy, because they were so thickly potted many had firing cracks due to uneven structural stresses and strains. Presumably, there was a high and costly failure rate when producing such ambitious objects. The court increased production and decided to outsource some imperial pieces to other kilns, which had to adhere to the demands put on them by imperial officials. These semi-independent Jiajing kilns had access to high quality materials, such as imported cobalt, but they were forced to pay a high price for it. Good quality cobalt was in high demand, the best sources and therefore most expensive, came from outside China. So, during the Jiajing period (1522-1566) imported cobalt was often mixed with cheaper indigenous supplies of this hard lustrous bluish grey metal. When you paint unglazed biscuit fired porcelain with cobalt it appears as a dull greyish black, miraculously turning blue after glazing and firing. It is referred to as underglaze blue, but I don't think that is really accurate, during firing the blue rises up into the glaze, staining it. In cross-section you can see the blue in the glaze. It is that depth of colour through the glaze that gives blue and white porcelain its unmistakable look. In the firing, if the cobalt is applied to thickly, there can be areas where the cobalt brakes out of the glaze. It sits on the glaze surface and becomes black once more, due to contact with the kiln atmosphere. The present dish has a good colour and is likely to have been painted with a high concentration of imported cobalt. The kilns had to work out how to pot and fire some of the heaviest porcelain objects ever produced. Many other Jiajing porcelain objects also had firing faults; it seems that absolute perfection wasn't essential. A large number of porcelain objects were ordered for the emperor, for the court and palaces. There were also many imperial porcelain orders for tribute pieces, an important part of Chinese diplomacy were the gifts to foreign rulers and dignitaries. Not just porcelain, but a vast array of objects and living things were deemed to be valuable gifts, to forge new alliances, or shore up fragile existing ones. This was perhaps especially important in China, where invasion was a never-ending worry, despite walls, armies and alliances.

Jiajing 1522-1566.

Ming Emperor of China.

Jiajing lived from the 16th of September 1507 to the 23rd of January 1567. His father was the Zhengde Emperor (1505 - 1521). From the beginning of Jiajing's reign, he was infatuated with young women and Taoist pursuits. He was known to be a cruel and self-aggrandizing emperor, and he also chose to reside outside of the Forbidden city in Beijing, like his father Zhengde Emperor, he made the decision to reside outside the Forbidden City. In 1542, he relocated to the West Park located in the middle of Beijing, west of the Forbidden City. So,he could live in isolation while ignoring state affairs. Jiajing employed incapable individuals such as Zhang Cong and Yan Gao, on whom he thoroughly relied on to handle affairs of state. He abandoned the practice of seeing his ministers altogether from 1539 onwards and for a period of almost 25 years refused to give official audiences, choosing instead to relay his wishes through eunuchs and officials. This eventually led to corruption at all levels of the Ming government. Jiajing's ruthlessness also led to an internal plot by his concubines to assassinate him in 1542 by strangling him while he slept. The plot was ultimately foiled, and all of the concubines involved were summarily executed. During the Jiajing reign, Chinese peasants began to expand their agricultural crops to include species native to Central and South America. In the 1530s, groundnuts cultivation was documented in Jiangnan, having spread there from Fujian Province. It is believed that Fujian peasants acquired it from Portuguese sailors. The Portuguese ordered porcelain from China at this period.

Portrait of Jiajing (lived from 16th of September 1507 to 23rd of January 1567).

National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Jiajing Porcelain From Robert McPherson Antiques

From Our Sold Archive.

Condition

Two large rim cracks c.45 mm, chip to footrim. The surface scratched.

Size

Diameter : 23.5 cm (9 1/4 inches).

Condition

Some minute rim chips and fritting

Size

Diameter : 14 cm (5 1/2 inches)

Provenance

A Private English Collection Acquired c.1970.

Stock number

24492

References

For a Ming bowl export ware bowl, Jiajing mark and period see : Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istanbul, A Complete Catalogue II, Yuan and Ming Porcelains (Regina Krahl, Sotheby's 1986) page 681 item 1103.

Condition

There is a slight loss to the top of the vase.

Size

Height : 29 cm (11 1/4 inches)

References

For various related vases of this form as well as ewers based on this shape dated as mid-16th century see : Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istanbul, A Complete Catalogue II, Yuan and Ming Porcelains (Regina Krahl, Sotheby`s 1986) pages 658 and 659. For a vase of this form with similar decoration dated as late 16th century see : Chinese Porcelains From The Ardebil Shrine (John Alexander Pope, Smithsonian Institute, Freer Gallery of Art, Lord Baltimore Press Inc, 1956.) page 140, plate 109, item 29.468. We would like to thank Mr Stuart Balmer for the references above. For a square vase of this type see : Exhibition of Transitional Wares for the Japanese and Domestic Markets, S.Marchant & Son, 11th - 30th June 1989, page 5, plate 3.

Condition

in excellent condition, there is a firing crack to the base it starts from some firing faults. The interior of the bowl has some wear and the rest of the bowl shows some signs of wear and very fine scratches. The glaze is bright and the general appearance is bright and the glaze looks shiny. The rim of the bowl is not even it being a bit warped as these bowls often are.

Size

Diameter : 28.5 cm (11 1/4 inches)

Stock number

24732

References

For a very similar Ming Porcelain bowl see : Chinese Blue and White Ceramics (S.T. Yeo & Jean Martin, South East Asian Ceramic Society, 1978) page 152, plate 57. A Further very similar Ming Porcelain bowl can be seen in : Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istanbul, A Complete Catalogue II, Yuan and Ming Porcelains (Regina Krahl, Sotheby's 1986) page 643 plate 973. Another Ming bowl of this type from the collection of Sir Percival David is now at the British Museum C610. Also see our sold item 215411.