An Inscribed Tianqi Ko-sometsuke Ming Porcelain Bowl for the Japanese Market.

An Inscribed Tianqi Ko-sometsuke Porcelain Bowl for the Japanese Market, Jingdezhen Kilns, Late Ming, Tianqi Period (1621-1627). The cobalt blue has a gray tinge to it, depending on the light.

The Poem :

It can be translated as tán ji : Discussing life’s mysteries (referring to profound truths, existential questions, or the workings of fate). Wàng suìyuè Time slips away unnoticed (literally ‘forgetting the passage of years). yī xià A single laugh (symbolising effortless detachment or enlightenment) ào qiákūn (‘defying heaven and earth’ it implies transcending worldly constraints – ‘heaven and earth’, representing the universe or mortal realm. The tone and philosophy of this verse captures a Daoist or Zen-like spirit of detachment, where wisdom dissolves temporal concerns and inner freedom transcends wordly boundaries. The “laugh” embodies enlightenment, lightness, and liberation from life’s burden’s. This translation, as well as the analysis are thanks to Koh Nai King. The philosophy, the feels and the meaning behind this short poem brings it to life. It makes me aware of how difficult it is to connect with Chinese art and culture, without a deep understand of its language and culture. I really am so grateful to Koh Nai King for bring life to these words.

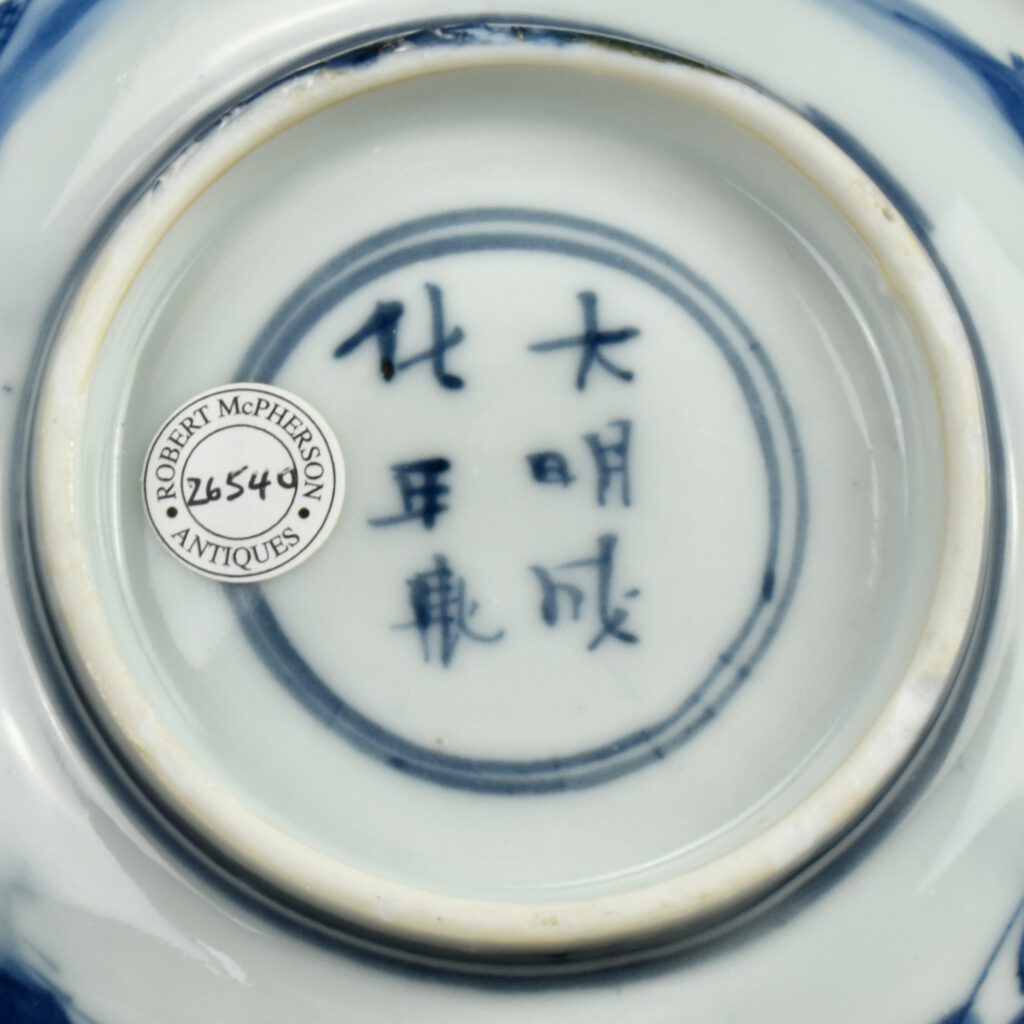

Most Ko-sometsuke porcelain comes in the form of small, medium and large dishes, many are moulded in the form of leaves, animals, vegetables etc. There are also bowls but they are not as common. The present shallow bowl might have been used for serving food at the Kaiseki meal which accompanies the Tea Ceremony. The scene to the exterior of this thinly potted bowl shows a small fishing vessel sheltered under a willow tree, with a figure on the promontory observing the person in the boat. To the left of the scene is a two line inscription. To the left of the inscription the water continues with a rocky promontory and mountains in the distance. The scene is then divided by rocks and swirling clouds, a typical device used during the Transitional period. The well is decorated in a similar vein to the exterior. The base with a pseudo-Chenghua Ming mark (1465-1487).

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

SOLD

- Condition

- In good condition, typical Mushikui (insect-nibbled) rim.

- Size

- Diameter 14.5 cm (5.7 inches). Depth 5.7 cm (2.2 inches).

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 26540

Information

Ko-sometsuke and Ko-akai : Ming Porcelain Made For Japan

Both of these terms Japanese terms refer to Chinese porcelain made for the Japaneses market, they are pieces that were used for the Japanese tea ceremony or closely associated with it. Ko-sometsuke is a term used to describe Chinese blue and white porcelain made for Japan, while Ko-akai refers to the porcelain decorated with enamels. This late Ming porcelain was made from the Wanli period (1573-1620), through the Tianqi period (1621 - 1627) ending in the Chongzhen period (1628-1644), the main period of production being the 1620'2 and 1630's. The porcelain made in China for Japanese reflected a rise in interest of the Japanese tea ceremony, but it also coincided with the beginning of porcelain production in Japan (from c.1610/20). The porcelain objects produced in China were made especially for the Japanese market, both the shapes and the designs were tailored to Japanese taste, the production process too allowed for Japanese aesthetics to be included in the finished object. Its seems firing faults were added, repaired tears in the leather-hard body were too frequent to not, in some cases, be deliberate. These imperfections as well as the fritted Mushikui (insect-nibbled) rims and kiln grit on the footrims all added to the Japanese aesthetic. These imperfections were something to be treasured by the Japanese, they reflect an imperfect world and the aesthetics of Wabi-Sabi. These 'faults' was an anathema to the Chinese but they went along with it to satisfy the needs of their Japanese customers. The shapes created were often expressly made for the Japanese tea ceremony, especially the meal associated with tea drinking, the Kaiseki. Small dishes for serving food at the tea ceremony are the most commonly encountered form. Designs, presumably taken from Japanese drawings sent to China, these are very varied and often extremely imaginative. They often used large amount of the white porcelain contrasting well with the asymmetry of the design, sometime the Chinese couldn't help themselves but to fill in these gaps with 'excess' decoration. Many other forms were made, among them are charcoal burners, water pots, Kōgō (incense box) as well as variously shaped dishes in the form of fish, fruit or familiar country animals.