Kraak Ware Porcelain

What is Kraak Ware – A Few Notes

Introduction

The term Kraak ware or Kraak porcelain is know by people interested in all sorts of different types of ceramics. Its recognisable style of panels and borders that is associated with Chinese porcelain, but it is a style of decoration that has spread across the globe. Porcelain and pottery in the Kraak style has been made as far a field as the Netherlands and Japan. It has been through times of immense popularity as well as being less popular, but it has been with us in one form or another since its conception in China in the 16th century.

It is generally known as an export ware made for the West, but it has been found in Royal Chinese tombs and graces palaces in the Middle and Near East.

- Teresa CanapeIn the past scholars postulated various theories concerning the origins of the word Kraak, which came to be commonly used in the West in the twentieth century. The earliest textual evidence known thus far of the use of the term ‘carracke’ refers to dishes which, in all probability, were Kraak porcelain dates to 1596. An ECA Orhans Court inventory from Exeter, England, dating to November of that year mentions that the apothecary Thomas Baskerville left ‘6 Carracke’ dishes.

What is Kraak Porcelain

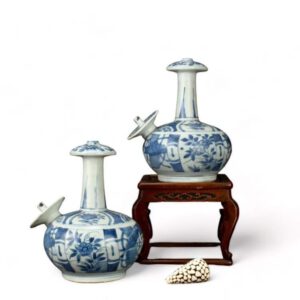

Some of its main characteristics include borders divided into panels, often with a wider panel framed by thinner ones. Shapes supplied by the West, especially the Dutch were common. These included bowls and dishes with everted rims, closed forms such as beer mugs as well as mustard pots. Moulds were often used, not just to form the pieces but to decorate the surface with relief designs. Many Kraak porcelain objects have mouled panels that serve as a guide for the painted decoration which is nearly always in underglaze cobalt blue.

The porcelain is dense fine-grained and rather pure white but prone to firing faults and imperfections. Kraak ware often has an undulating glaze with a slight blue or blue-grey appearance. The rims and edges sometimes have areas of exposed porcelain where the glaze did not adhere to the sharp edges. Many pieces subsequently shed glaze from the surface of the porcelain, these ragged edges of dishes, bowls etc are referred to as fritted. Kraak ware was often glaze-fired on a bed of sharp grit, pieces of grit can often be seen attached to glaze around the footrim. The bases were finished on a wheel with a tool that cut into the body to create the base and leave a foot. These tools were not always well adjusted to the speed of the wheel when a form was being worked on, this can leave shallow radial marks, referred to as chatter-marks.

These traits are shared with late Ming porcelain made for the Japanese market, perhaps indicating a method of production the Chinese felt was suitable for export ware.

Most Kraak ware was made at the enormous group of kilns at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi, Southern China. Some of these private kilns have recently been excavated and shards of Kraak ware recovered from the Old City Zone. One of the most active kilns making Kraak porcelain was the Guanyinge, where some of the finest Kraak ware was made.

Kraak porcelain is a type of export porcelain, from the beginning to the end it reflects the history of international trade, especially that between the East and West. However, shards of Kraak ware have been found off the Coast of America, Africa, the Middle and Near east.

Defining the Term Kraak Ware

Kraak ware is a somewhat contentious term, like so many definitions in art history it is a help and at the same time it can be a hindrance. It is perhaps true to say there is a clearly defined group of porcelain that can be called Kraak ware and other pieces that can be included or put into a subcategory. I once chaired a specimen meeting dedicated to Kraak ware at the Oriental Ceramics Society in London, the debate as to what constituted Kraak ware got rather heated. Personally, I still have trouble with including some pieces that are referred to as Kraak under the heading of Kraak ware.

It is referred to as Kraak ware, but it is really a term used to describe a type of Chinese porcelain made between the latter part of the 16th century to the middle of the 17th century. Later Chinese porcelain, for example from the Kangxi period (1662-1722) that looks like Kraak porcelain is described as being Kraak style porcelain. Japanese, Islamic and European ceramics are all referred to as Kraak style rather than Kraak ware. This contrasts with Delftware, which is a term used for pieces made in the Netherlands as well elsewhere.

- Richard Carew, Survey of Cornwall (first Published in 1602)Here the great carrack which Sir Francis Drake surprised in her return from the East Indies unloaded her freight

Kraak Ware – Origins and Trade

The earliest Kraak porcelain is thought to have started to be produced during the short reign of Longqing (Ming Dynasty,1567-1572). It is perhaps no coincidence that during Longqing’s reign a partial lifting of the ban on maritime trade was implemented. The Emperor Longqing allowed traders to use junks to export exclusively from the port of Yuegang in Zhangzhou, Fujian province. Licensed trade was allowed with any country except Japan, Kraak ware and other porcelain were made for especially for Japan in large numbers a little later.

According to Teresa Canepa (1) “In the past scholars postulated various theories concerning the origins of the word Kraak, which came to be commonly used in the West in the twentieth century. The earliest textual evidence known thus far of the use of the term ‘carracke’ refers to dishes which, in all probability, were Kraak porcelain dates to 1596. An ECA Orhans Court inventory from Exeter, England, dating to November of that year mentions that the apothecary Thomas Baskerville left ‘6 Carracke’ dishes”. She goes on to say that although spelt differently the term Kraak derives from the English word Carracke named after a Portuguese trading boat carrack. Sir Francis Drake seized the Portuguese carrack San Felipe off the Azores in 1587. The cargo, which contained Chinese porcelain, was taken to Plymouth in England. Teresa Canepa (1) again, “Richard Carew in his Survey of Cornwall (first published in 1602), wrote: ‘Here the great carrack which Sir Francis Drake surprised in her return from the East Indies unloaded her freight”.

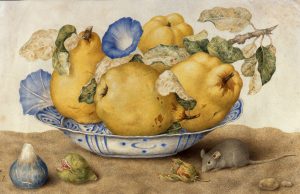

The export of Kraak porcelain was important to the West, in the 16th and 17th century Chinese porcelain was highly prized and initially only available to the wealthiest in society. The Portuguese and the Dutch vied for the profitable concessions and trade routes to China and Japan. It was the Dutch who climbed to the top position in this trade war, not just though force but diplomacy as well. The Dutch East India Company run by shareholders was formed in 1602. The V.O.C. (Verenigde Oostindische Companie), was a unique experiment in international commerce and trading links. The enormous wealth of the company, the rise of the Dutch Republic and the Dutch Golden Age are all interlinked. This extraordinary period of knowledge, wealth and social change is reflected in the collections of paintings belonging to museum galleries around the world. Many of them have 17th century Dutch still life paintings that reflect this new wealth, much of it generated by the V.O.C. Painting include the exotic, for example, shells from far off warm waters, lemons as well as Kraak porcelain.

Dating Kraak Ware

These paintings provide a wonderful, in fact unique view of Chinese porcelain set in a 17th century European context. Further, they go some way in helping us date the porcelain. This is not always as straight forward as it seems, not all paintings are dated and the porcelain in the paintings might be several decades old when the painting was done.

A far more helpful guide is that of Kraak porcelain recovered from shipwrecks, which also has its problems, but is I believe by far the most important dating tool. Porcelain recovered from the wreck might be dated, but this is very rare. Normally the porcelain is datable because the date of the shipwreck is recorded.

Work done in America by Edward Von der Porten and other on early Wanli wrecks has been invaluable. For example, the work on the Manilla Galleon San Felipe of 1576 gives us an idea of the very earliest pieces we would call Kraak ware. Pieces recovered from the excavation at the Drakes Bay in California give a real understanding of a cargo from 1579 (2; Raymond Aker and Edward Von der Porten).

The Witte Leeuw was a V.O.C. yacht, part of a convoy returning to the Netherlands with spices, Chinese porcelain and over 1,300 diamonds. It lost when its magazine exploded during an engagement with two Portuguese carracks off Saint Helens on June 13th, 1613. The items recovered include numerous shards of Kraak porcelain, some can be seen on the website of the Rijksmuseum.

Footnotes

- Jingdezhen to the World, The Lurie Collection of Chinese Export Porcelain from the Late Ming (Teresa Canepa, 2019. ISBN 978-1-912168-09-5)

- Discovering Francis Drake's California Harbor (Raymond Aker and Edward Von der Porten, 2010. Drake Navigarors Guild)

Examples of Chinese Kraak Porcelain and other Ceramics in the Kraak Style

Robert McPherson Antiques : Sold Archive 25997.

Robert McPherson Antiques. Sold Archive : 25927.