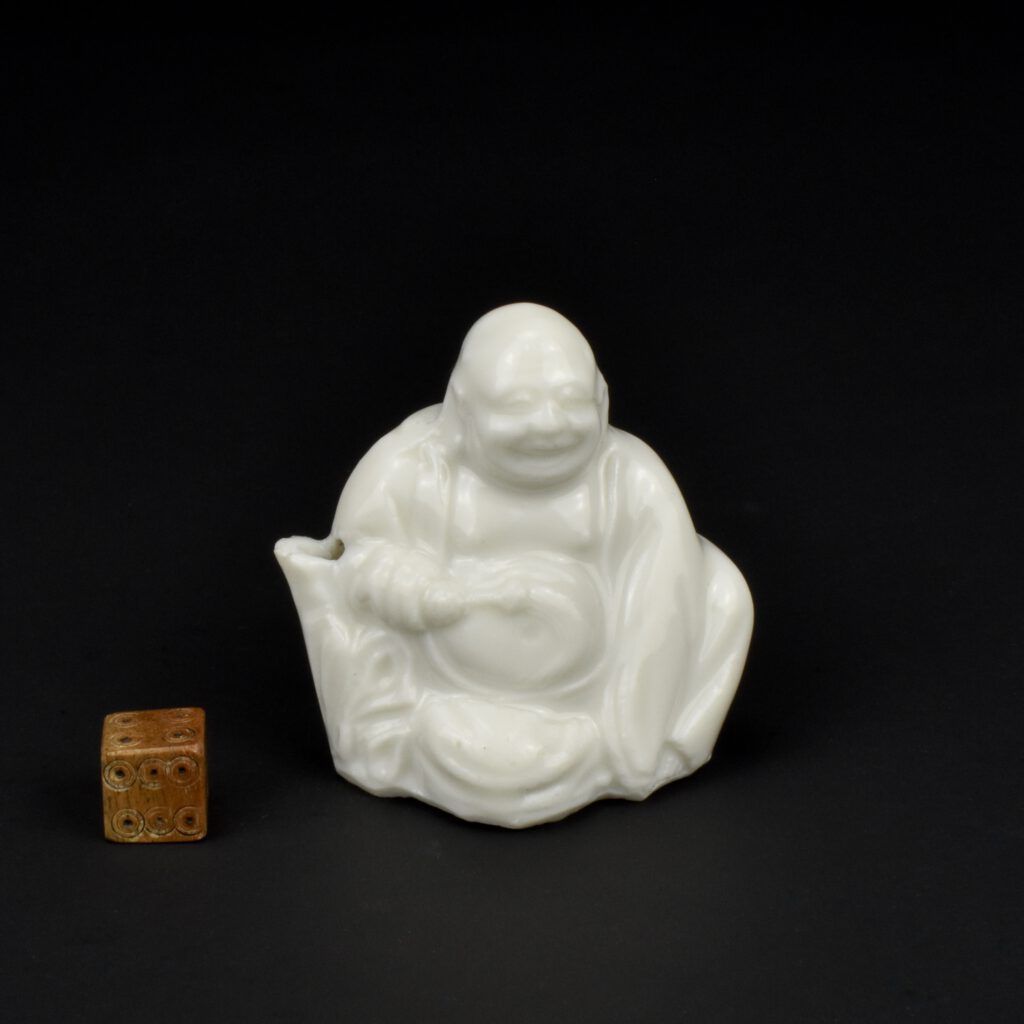

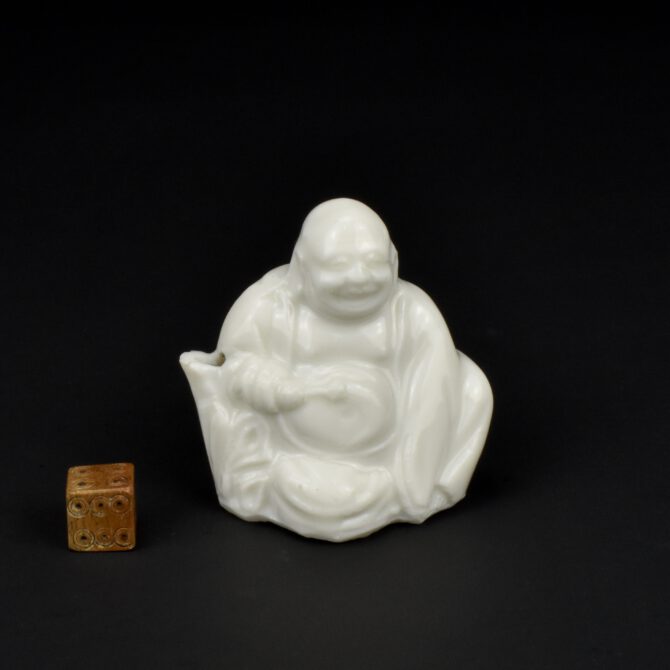

A Kangxi Blanc de Chine Porcelain Water Dropper

A Kangxi Blanc de Chine Porcelain Water Dropper, Dehua Kilns, Fujian Province, Kangxi period (1662-1722). This thinly potted Kangxi porcelain water dropper was made in a two-piece mould with the base pushed in by hand. The moulding is crisp for this type of object.

The term `Scholar’s object` refers to something used by a Chinese scholar in his or her studio, it includes everything from scroll-tables, desks, screens, and chairs to the smaller objects found on the scholar’s desk. The material used for these desk objects varied greatly, from bamboo to stone, ivory, wood, and metal, but ceramics were by far the most commonly used material, even though ceramics rated lowest in ranking of importance. Bamboo, ivory, or wood might not be durable enough and metal was sometimes too heavy but ceramic objects could be thrown or moulded into an infinite variety of forms. Most of the objects made centred around the functions of writing and painting. Brushpots of different sizes and shape were needed to take the various types of brush, the same applies to brush rests. Water-droppers for adding water to dry solid ink when it was ground on an inkstone, as well as the inkstones themselves were all needed, as were water-pots and brush-washers. All of these could be made of porcelain. But these were not merely functional items, they conveyed symbolic mean, often enhancing scholarly virtues and the wish for longevity. They were meant to inspire the writer, poet, and artist but it is clear they could also exhibit a great sense of humour, sometimes having almost childlike quality. Objects for the scholar’s desk were made from many different ceramic bodies, during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) Qingbai porcelain was most frequently used, often in moulded forms. Blue and white porcelain objects became popular from the Ming dynasty onwards. By 17th and early 18th century, Blanc de Chine, and biscuit porcelain with coloured glazes such as green, aubergine or turquoise were also popular. Some of these objects were shipped to Europe at the time. The records of the Dashwood, a British trading vessel, were sold at in September 1703, this Supra-cargo, include 10,800 `square toys`. These were Blanc de Chine seals, I have bought and sold many of these over the years. Some are uncut, some have mould seals to the base and could have been used in China, there seals that were engraved, its likely these were not exported. However, the label, ‘square toys’, shows that in Britain they were seen as novelties to show friends and to be on display in cabinets. I’m not sure if the Chinese scholarly class would have approved.

SOLD

- Condition

- In good condition, shallow chips to the edge of the spout.

- Size

- Height 5.8 cm (2 1/3 inches). Depth 3.3 cm.

- Provenance

- From a Private English Collection of Blanc de Chine Porcelain.

- Stock number

- 26369

Information

Blanc de Chine Porcelain

The porcelain known in the West as Blanc de Chine was produced 300 miles south of the main Chinese kiln complex of Jingdezhen. The term refers to the fine grain white porcelain made at the kilns situated near Dehua in the coastal province of Fujian, these kilns also produced other types of porcelain. A rather freely painted blue and white ware, porcelain with brightly coloured `Swatow` type enamels as well as pieces with a brown iron-rich glaze. However it is the white blanc de Chine wares that have made these kilns famous. The quality and colour achieved by the Dehua potters was partly due to the local porcelain stone, it was unusually pure and was used without kaolin being added. This, combined with a low iron content and other chemical factors within the body as well as the glaze, enabled the potters to produce superb ivory-white porcelain.

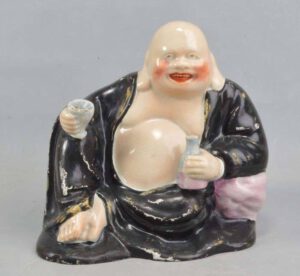

Budai / Hotei / Pagod

Budai (Hotei in Japanese) is a Chinese deity. His name means `Cloth Sack`, and comes from the bag that he carries. According to Chinese tradition, Budai was an eccentric Chinese Zen monk who lived during the 10th Century. He is almost always shown smiling or laughing, hence his nickname in Chinese, the Laughing Buddha. In English speaking countries, he is popularly known also as the `Fat Buddha`. In China Porcelain figures such as the present example would have been used in a family shrine while offering prayers, but in the West they would be seen as exotic curiosities, sometimes referred to as Magot or Pagod. The term Magot was used from as early as the mid 17th century to describe the European heavy set or bizarre representations in clay, plaster, copper or porcelain of Chinese or Indian figures. The term is usually used to describe the European porcelain. Pagoda Figure comes from the term pagode or religious figures housed in pagoda shrines. (Kisluk-Grosheide, `The Reign of Magots and Pagods`, Metropolitan Museum Journal 73, 2002, pp. 177, 181, 182, 184).