A Large Fine Quality Transitional Porcelain Jar and Cover 17th Century

A Fine Quality Late Ming Blue and White Jar and Cover, Chongzhen Period (1627 – 1644). This Transitional blue and white porcelain jar and cover is very similar to one in a painting of 1669 by the Dutch artist William Kalf (see references below the photographs). This sturdy High Transitional Porcelain jar with its deep cover is typical of high quality porcelain imported by the V.O.C. Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie at this period. The heavily potted ovoid porcelain jar has a tall neck which has the glazed wiped clean around the collar, so the high flat cover can fit over the neck and rest on unglazed porcelain, thus preventing chipping. The neck is waisted and the top is unglazed. The flat base is unglazed as is typical with this type of Transitional jar. The main designs is formed of two large leaf-shaped reserves. One of which is of peony and another flowering plant with grasses among a scholar’s rock. The other side is decorated with what appears to be a flowering prunus with other flowers and an insect. These main designs are separated by two smaller panels, one on each side. One of the smaller panels is almost circular with a bird on a branch with bamboo and grass, perhaps a winters scene. The other side has a small oval panel with flowering prunus and pine. All four panels are set against a blue cracked-ice ground which is punctuated by stylised flowering scrolling lotus.

SOLD

- Condition

- In excellent condition, no damage. Firing fault - the central lutting line shows slightly, far less than it appears in the photographs. There is a minor firing fault to the rim.

- Size

- Height 28 cm (11 inches)

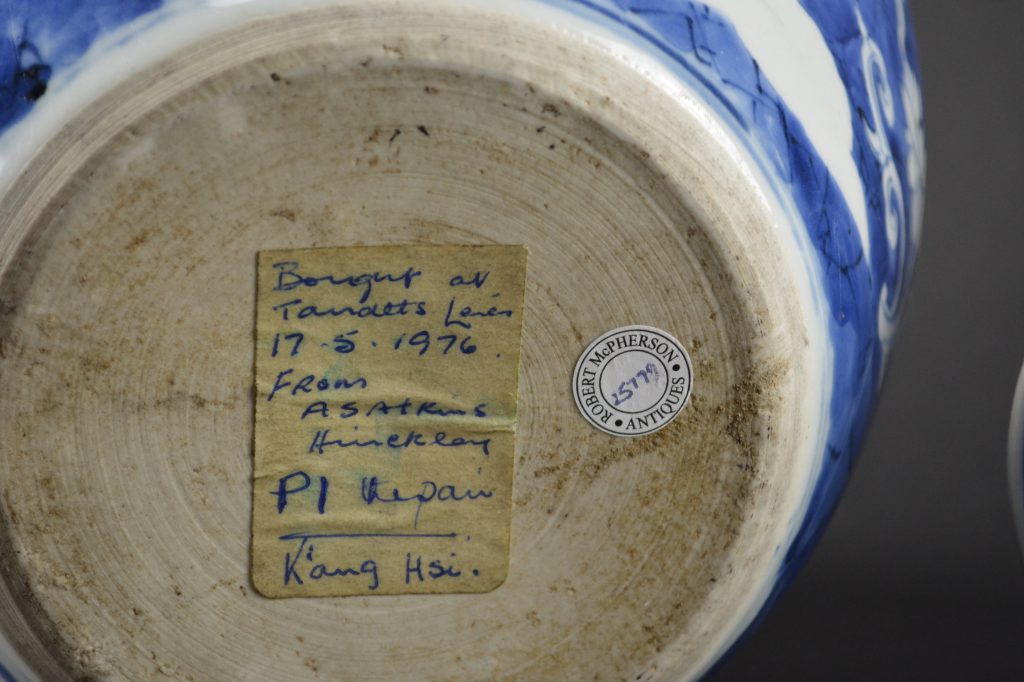

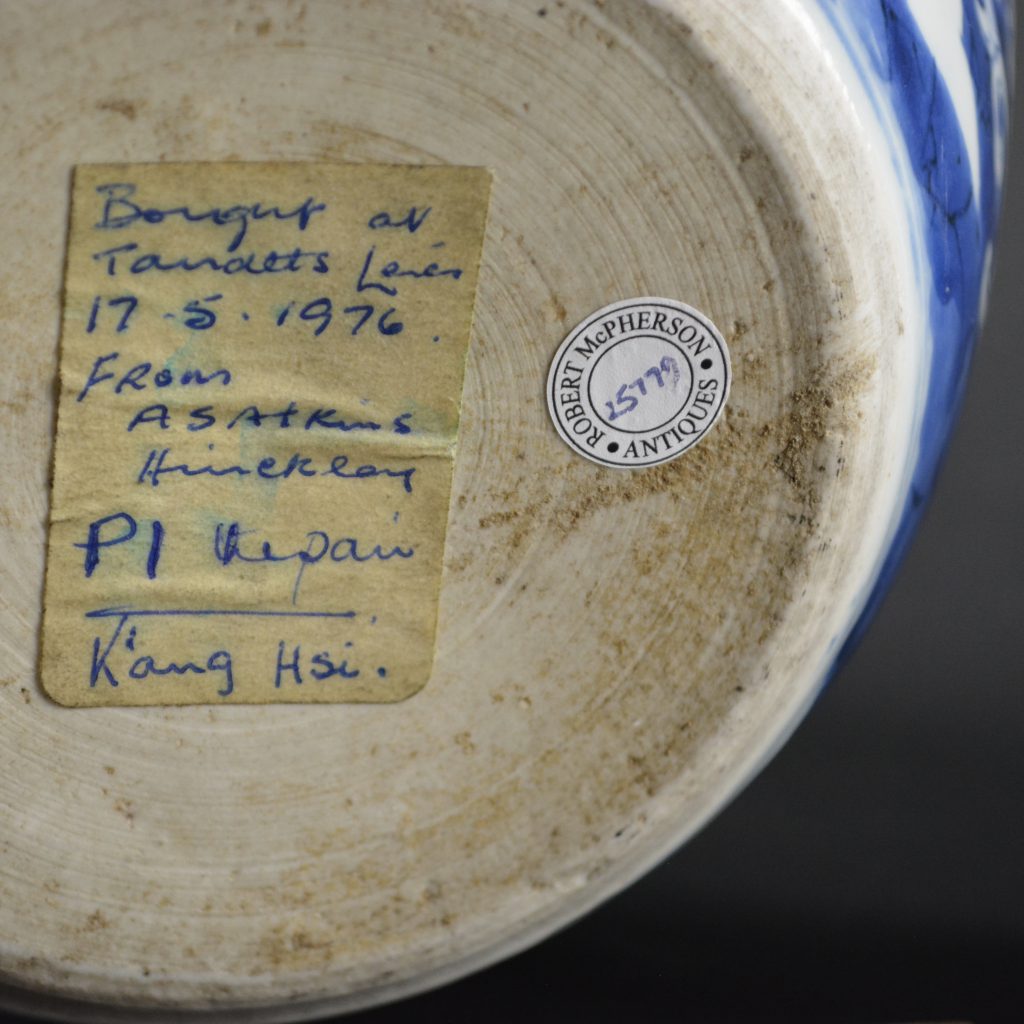

- Provenance

- An old label to the base dates the jar as K'ang Hsi (Kangxi) and says where was purchased (I cannot work out exactly what it says) on the 17th of May 1976. Hong Kong private collection, Woolley and Wallis Auction 15th July 2006.

- Stock number

- 25779

- References

- For similar Transitional Porcelain Jars of this type see : Christie's Amsterdam, Fine and Important Late Ming And Transitional Porcelain, Recently Recovered from an Asian Vessel in the South China Sea. Property of Captain Michael Hatcher. Christie`s Amsterdam 14th March 1984.

Information

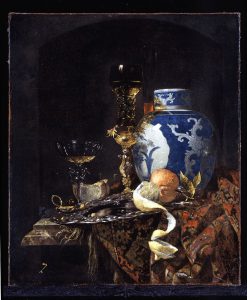

A Similar Transitional Porcelain Jar and Cover

in Willem Kalf's Painting of 1669

This painting by William Kalf of 1669 is typical of still-life painting during the Dutch Golden Age. Kalf was at the forefront of this luxurious painting of luxurious objects and dominating this image is late Ming jar and cover from around 1640. Exotic, oriental and like nothing else in Europe this type of Chinese blue and white fascinated the Dutch, indeed they are famous copies of it, Delftware. This import by the V.O.C. was especially made for the Dutch market and fitting on top of large pieces of oak furniture, so popular at the time. Further exotic items in Kalf's still life include a 'Turkey carpet', citrus fruit but also luxury items made in the Netherlands, such as the silver dish. In the 1650s and '60s, as the Netherlands flourished due to its commerce and pro-commercial politics, Kalf perfected the pronk (display) still life to exhibit its prosperity. Goethe thought he succeeded, saying of Kalf's paintings that "there is no question that should I have the choice of the golden vessels or the picture, I would choose the picture."

A Similar Transitional Porcelain Jars

From The Hatcher Cargo of c.1643

Hatcher Cargo

Hatcher Cargo was the first porcelain cargo from a shipwreck to come on to the market. It was sold in several auctions in Christie`s Amsterdam in 1984 and 1985. It remains one of the most important cargoes of shipwreck ceramics ever recovered, despite the lack of historical evidence recorded by the salvage team. Two porcelain covers dated 1643 helped date the wreck but this needed corroborating to give a firm date of the wreck and it`s cargo. The dating of the porcelain from the Hatcher Cargo is based on several elements. Firstly, the ceramics recovered form a coherent group, in other words they appear to all have been made at the same time. Secondly comparative dating was used to corroborate the date of the porcelain. For example, blue and white porcelain dishes decorated with a coiled serpent recovered from the Hatcher Cargo match an important dish from the fall of the Ming dynasty, formerly in the Percival David Foundation, now at the British Museum London, this dish can be dated to 1644 – 1645. Other comparative dating is also consistent with the presumed date of the porcelain. However, the most important dating reference remains the two covers recovered from the wreck datable by inscription to the spring of 1643. Although the the Ming dynasty officially ended in 1644 the transition from the Ming to the beginning of the Qing was messy and protracted. The porcelain made during this period of civil war and chaos is referred to as `Transitional Porcelain`. It covers the period from the last Ming Emperors until the early years of the Kangxi period, which is normally given a date of about 1620 to 1670 . The Hatcher Cargo is a vital dating tool for this previously poorly understood period of Chinese porcelain production.

Shunzhi was emperor of Manchuria between Oct. 8, 1643-Oct. 30, 1644. Officially proclaimed emperor of China on Oct. 30, 1644. The Shunzhi Emperor (March 15, 1638–February 5, 1661?) was the second emperor of the Manchu Qing dynasty, and the first Qing emperor to rule over China proper from 1644 to 1661.