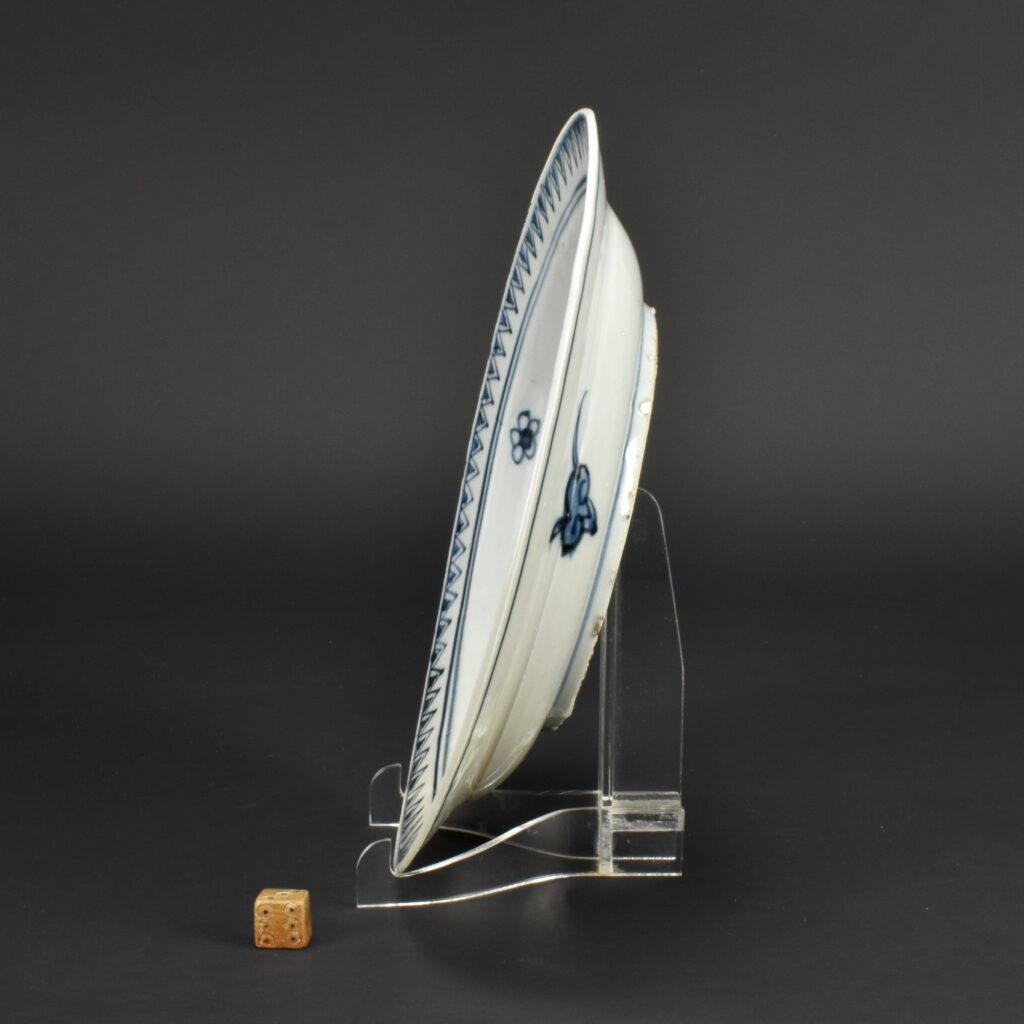

A Ming Ko-sometsuke Porcelain Dish, Tianqi Period 1621-1627.

A Ming Ko-sometsuke Porcelain Dish, Tianqi Period 1621-1627, Jingdezhen Kilns. This Chinese blue and white late Ming dish was made for the Japanese tea ceremony. The scene depicted represents a well-known theme, which appears in many different ways on Chinese and Japanese porcelain, that is The Three Friends of Winter. The Three Friends of Winter are represented by Pine, Bamboo and Prunus. These three plants signify perseverance as seen in nature during winter. Pine might be old, gnarled, misshapen by winter winds, yet it still survives, bamboo bends in the wind, throwing off snow and it survives the coldest winters. The plum, prunus family in general, flowers at the very end of the winter, heralding the arrival of spring. In this design, the bamboo is to the lower right, with angular pine entering overhead, and a broken, but still flowering, plum tree is to the lower left. The plum design is reflected in the border, with four facing prunus flowers placed asymmetrically. The border to the everted rim has a continuous sawtooth design. The base, which shows distinctive chatter marks, is painted with two concentric circles. Beyond the footrim are three Ruyi designs based on the Lingzhi (sacred fungus). Ko-Sometsuke is a term used to describe Chinese blue and white porcelain made for Japan. This late Ming porcelain was made from the Wanli period (1573-1620), through the Tianqi period (1621 – 1627) ending in the Chongzhen period (1628-1644), the main period of production being the 1620’2 and 1630’s. This porcelain made in China for Japanese reflected a rise in interest of the Japanese tea ceremony, but it also coincided with the beginning of porcelain production in Japan (from c.1610/20). The porcelain objects produced in China were made especially for the Japanese market, both the shapes and the designs were tailored to Japanese taste, the production process too allowed for Japanese aesthetics to be included in the finished object. It seems firing faults were added, repaired tears in the leather-hard body were too frequent to not, in some cases, be deliberate. These imperfections as well as the fritted Mushikui (insect-nibbled) rims and kiln grit on the footrims all added to the Japanese aesthetic. These imperfections were something to be treasured by the Japanese, they reflect an imperfect world and the aesthetics of Wabi-Sabi. These ‘faults’ was an anathema to the Chinese, but they went along with it to satisfy the needs of their Japanese customers. The shapes created were often expressly made for the Japanese tea ceremony, especially the meal associated with tea drinking, the Kaiseki. Small dishes for serving food at the tea ceremony are the most commonly encountered form. Designs, presumably taken from Japanese drawings sent to China, these are very varied and often extremely imaginative. They often used large amount of the white porcelain contrasting well with the asymmetry of the design, sometime the Chinese couldn’t help themselves but to fill in these gaps with ‘excess’ decoration. Many other forms were made, among them are charcoal burners, water pots, Kōgō (incense box) as well as variously shaped dishes in the form of fish, fruit or familiar country animals. For a Ming blue and white porcelain dish with this design and size see : Trade and Transformation, Jingdezhen Porcelain for Japan, 1620-1645, and for another Tianqi dish of this approximate size and the same design see : The Effie B. Allison Collection, Kosometsuke and Other Chinese Blue-and-White Porcelains, Exhibition at The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco March 2nd – June 6th 1982 : see ‘References’.

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

- Condition

- Typical firing faults and kiln grit to the base and foot.

- Size

- Diameter 20.8 cm (8.2 inches)

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 26274

- References

- For a Ming blue and white porcelain dish with this design and size see : Trade and Transformation, Jingdezhen Porcelain for Japan, 1620-1645 (Julia B.Curtis, China Institute Gallery, New York 2006) page 106, plate 587. For another Tianqi dish of this approximate size and the same design see : The Effie B. Allison Collection, Kosometsuke and Other Chinese Blue-and-White Porcelains, Exhibition at The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco March 2nd - June 6th 1982, page 29, plate 31.

- £ GBP

- € EUR

- $ USD

Information

The Three Friends of Winter

These three plants, Pine, Bamboo and Prunus, signify perseverance. Neither the Pine nor the Bamboo shed their leaves in winter and the Plum flowers at the very end of the winter, heralding the arrival of spring.

The Transitional Period

The roots of this unsettled period starts during the later part of Wanli`s reign (1573-1620). At the begging of his reign China was doing very well, new crops from the Americas such as peanuts, maize and sweet potatoes increased food production, while simplified taxes helped the state run smoothly. But this was not due to Wanli`s enlightened reign, but to his Mother championing a man that was to become the Ming dynasties most able minister, Zhang Zhuzheng (1525—1583). Wanli became resentful of Zhuzheng`s control but upon his death became withdrawn from court life. Between 1589 to 1615 he didn`t appear at imperial audiences, leaving a power vacuum that was filled by squabbling ministers. Mongols from the North raided as Japan invaded Korea. Wanli re-opened the silver mines and imposed new taxes but the money was lost due to corruption, as well as being frittered away by the indulgent Emperor himself . The next emperor of Ming China, Tianqi (1621-1627), was bought up in this self indulgent disorganised environment, at the very young age 15 his short reign started. He didn`t stand a chance. Tianqi made the mistake of entrusting eunuch Wei Zhongxian (1568-1627) who Anna Paludan in her excellent book “Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors” (Thames and Hudson, 1998) describes as “a gangster of the first order”. Tianqi was deemed to have lost the Mandate of heaven by the Ming people. Tianqi`s younger brother, the last of the Ming Emperors, Chongzhen (1628-1644), was not able to save the situation. The systems of administration had broken down, corruption was rife and so when a sever famine broke out in 1628 nothing much could be done. Anna Paludan describes the tragic end to the great Ming Dynasty “The final drama was worthy of a Greek tragedy. The emperor called a last council in which `all were silent and many wept`, the imperial troops fled or surrendered, and the emperor, after helping his two sons escape in disguise, got drunk and rushed through the palace ordering the women to kill themselves. The empress and Tianqi`s widow committed suicide; the emperor hacked off the arm of one daughter before killing her sister and the concubines. At dawn he laid his dragon robe aside and dressed in purple and yellow, with one foot bare, climbed the hill behind the now silent palace and hanged himself on a locust tree”. The Great Wall of China, started 2,000 years ago was built to protect China from the Northern barbarian hoards, it was often tested and sometimes failed. The Jin people invaded China, ruling the North between 1115 and 1234, it was their descendants the Manchus, Jurchens from south east Manchuria that took full advantage of the problems of the Ming dynasty. In 1636 they adopted a Chinese dynastic name, the `Great Qing` (Qing meaning pure). The first of the Qing emperors was Shunzhi (1644-1661) but for most of his reign his uncle ran the state. War raged on during this period and it wasn`t until the second Qing emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) that true peace was achieved. Kangxi was a wise and educated man, he became a highly successful emperor bringing China a long period of wealth and stability.

Lingzhi Fungus - Ganoderma lingzhi

Designs in Chinese art often include a Lingzhi Fungus or groups of them. For at leat two thousand years they have appeared in different guises but primarily it is the 'Mushroom of Immortality', it is associated with the god of longevity Shouloa. No exact species can be attributed to Lingzhi fungus but it is a member of the Ganoderma species and is still sold in Chinese herb shops today. Work into the precise nature of this fungus and its health benefits or otherwise are ongoing. A ruyi-sceptre has a part modelled on Lingzhi (sacred fungus), this sceptre is an ancient Chinese object that conveys the holder of it to have what he or she wants. So, the design could be interpreted as a bestowing the wish for children on the recipient of the dish.