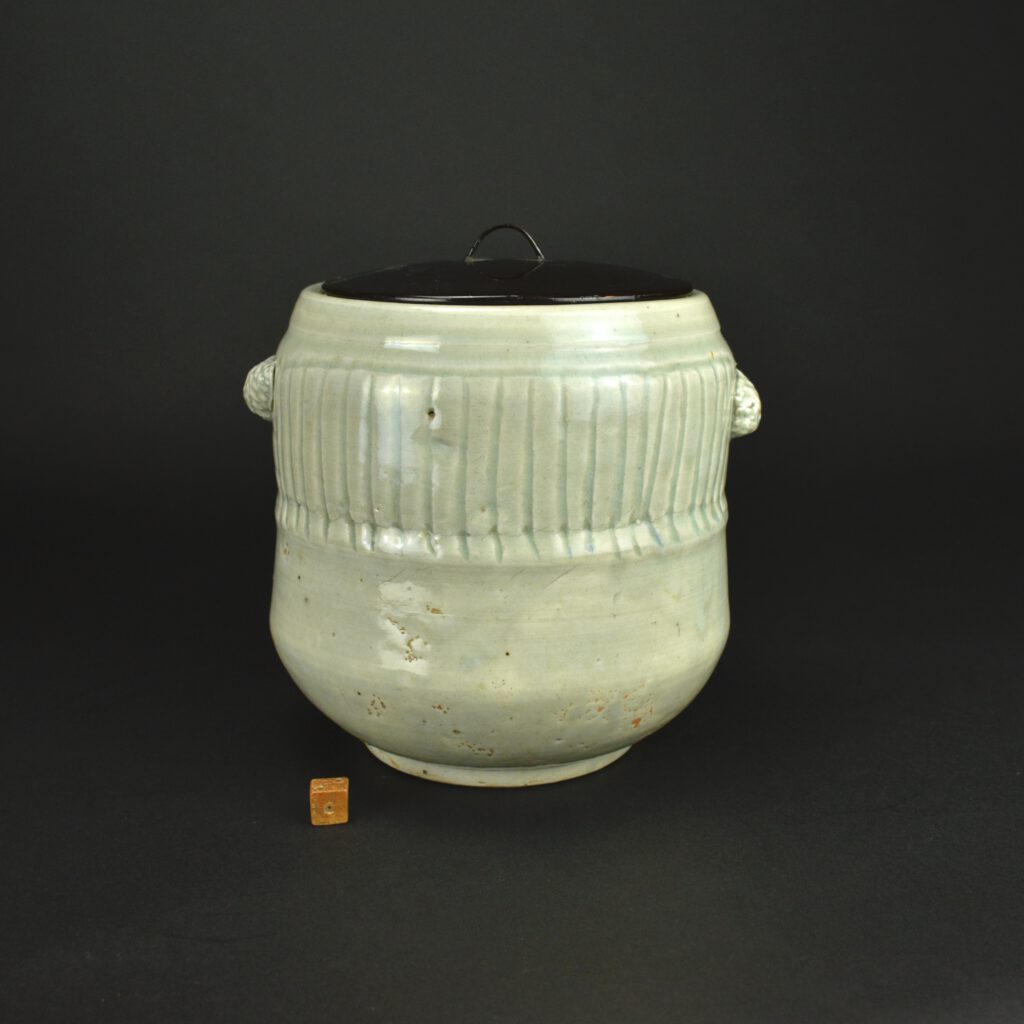

A Rare 17th Century Japanese Celadon Mizusashi

A Rare 17th Century Japanese Celadon Mizusashi (水指), a lidded water container for the Japanese tea ceremony. Perhaps Hasami, Kobayama kiln, c.1660-1680. There are earlier celadon Mizusashi dating to c.1630 to 1640 that have similar rough scratched decoration but I think this piece is later, the base has a pale iron-oxide applied to the concentric circle the piece was fired on, these didn’t come into use until about 1650 as far as I am aware. This Japanese celadon jar is closely related to pottery examples of the period, both in form but also in its aesthetic quality. It is beautifully made, so the use of rough incised decoration is a deliberate enhancement in the tradition of wabi-sabi. The rudimentary pinecone handles are made in a mould, they asymmetrically placed and no attempt has been made to smooth the edges, so the sharp edge of the mould-line shows. A Mizusashi is a container for cold fresh water, they are generally made of pottery and to a lesser extent porcelain but wood and metal versions were also made. Ceramic Mizusashi with lids of the same material are referred to as Tomobuta meaning ‘matching lids’. Often ceramic Mizusashi will a have custom-made lid of lacquered wood, especially lacking its original lid.

SOLD

- Condition

- In excellent condition, it would probably have had a ceramic lid, this has been replaced by a lacquered wood on (modern).

- Size

- height 16.5 cm (6 1/2 inches) Diameter at the top 14.5 cm (5 3/4 inches).

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 26242

Information

Wabi - Sabi A literal translation doesn't work well for the Japanese concept known of Wabi-Sabi. We have imprinted in us a sense of permanence connected with the Classical order, symmetry, things being right, perfect, pristine even. We know an Imperial Qing or Sèvres vase is good quality because it tells us so. The material, fine translucent porcelain, is decorated in rich colours, even gold, the surface filled with decoration that wears its wealth in clear public view. It is perfect and perhaps if we own it will get somewhere nearer perfection ourselves. The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi shows us something quite different. Life is imperfect, we are imperfect, the art of life is to live with it. Perhaps, the nearest we get to permanence is the inevitable realisation that transience is part of the ebb and flow of how things are. Nothing is perfect, Wabi-Sabi allows us to see the beauty inherent in imperfection, the rustic and the melancholy. A potter's finger marks on the surface of a pottery bowl, the roughness of a pottery. A ceramic surface can become a landscape in which the eye walks over humble cracks, uneven, faulty, the mind in austere contemplation. Wabi-Sabi can be condensed to 'wisdom in natural simplicity'.

Wabi-Sabi stems from from Zen Buddhist thought, 'The Three Marks of Existence' ; impermanence, suffering and the emptiness or absence of self-nature. These ideas came to Japan from China in the Medieval Period, they have developed over the centuries and have greatly affected Japanese culture. For example the Japanese tea ceremony, which is the embodiment of perfection, uses ceramics which are imperfect. It was not just the pottery made in Japan that needed to have a Wabi-Sabi nature but also the Chinese porcelain made for the Japanese tea ceremony. During the late Ming dynasty the Chinese supplied Japan with porcelain for the tea ceremony, not just for the ceremony itself but for the meal that was taken with it, the Chinese even supplied charcoal burners for them to light their pipes. This Chinese porcelain was made at Jingdezhen to Japanese designs, sent from Japan. The Japanese wanted the Chinese to work against their normal way, they requested firing faults, imperfections and unevenness. The Chinese were sometimes rather too precise in their making of these imperfections, often adding faults carefully and even symmetrically. I imagined they could have thought, 'why do our customers want us to make these things so badly'. Clearly Wabi-Sabi was lost on them.