A Rare Ming Porcelain Ko-akae Charcoal Container for the Japanese Market .

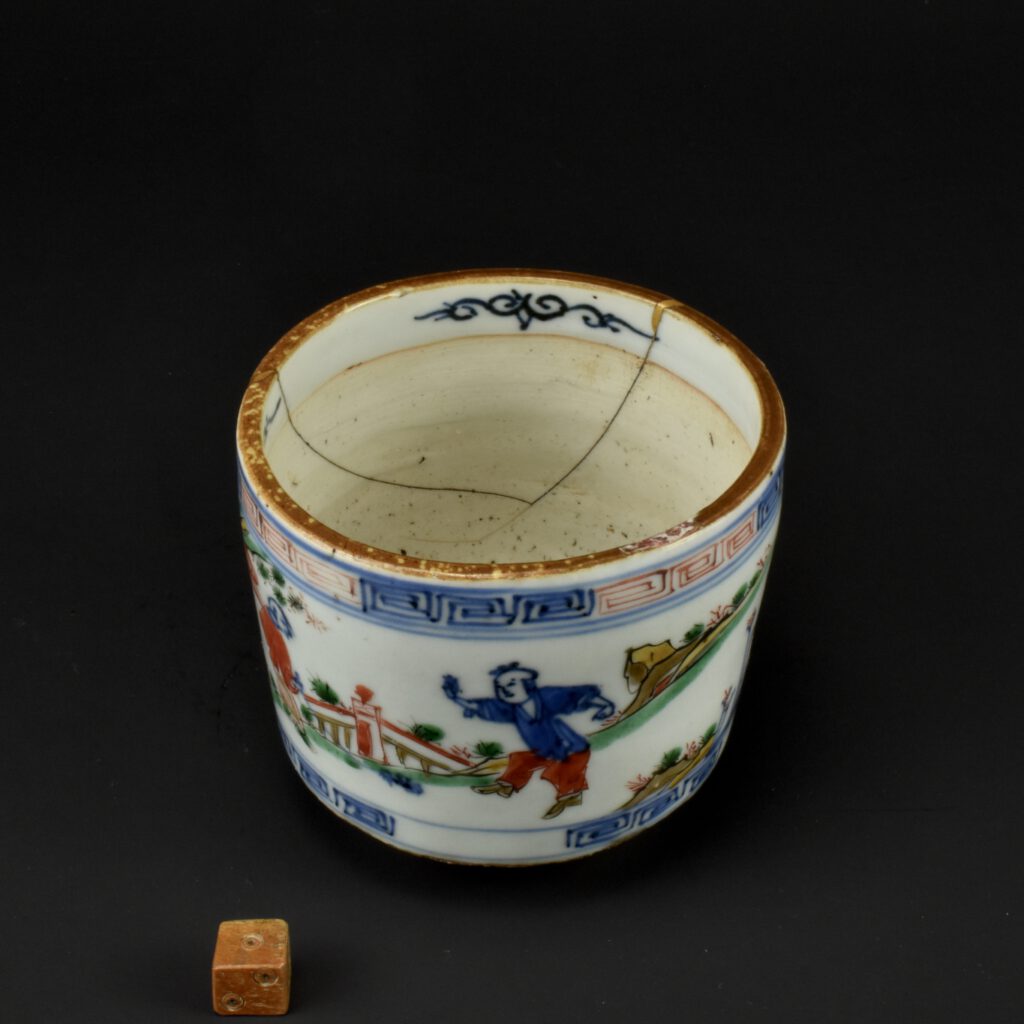

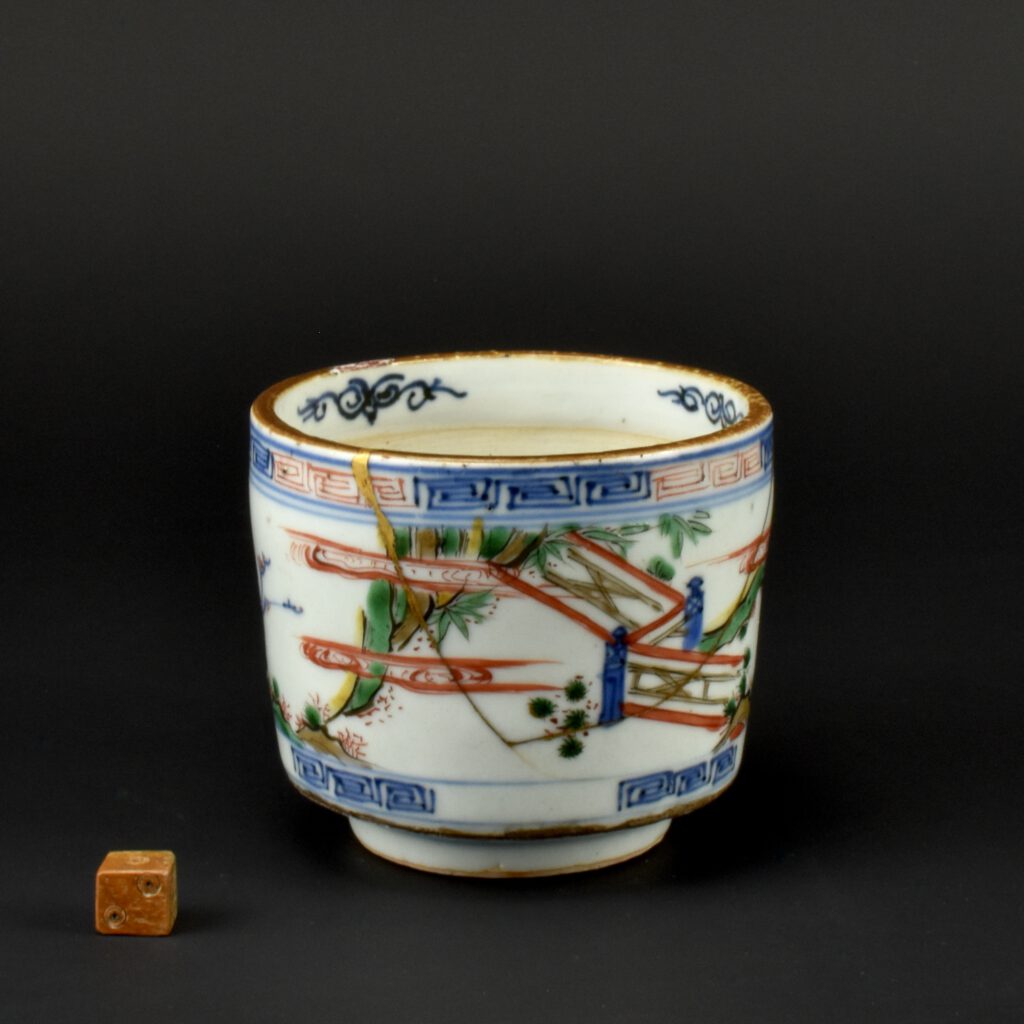

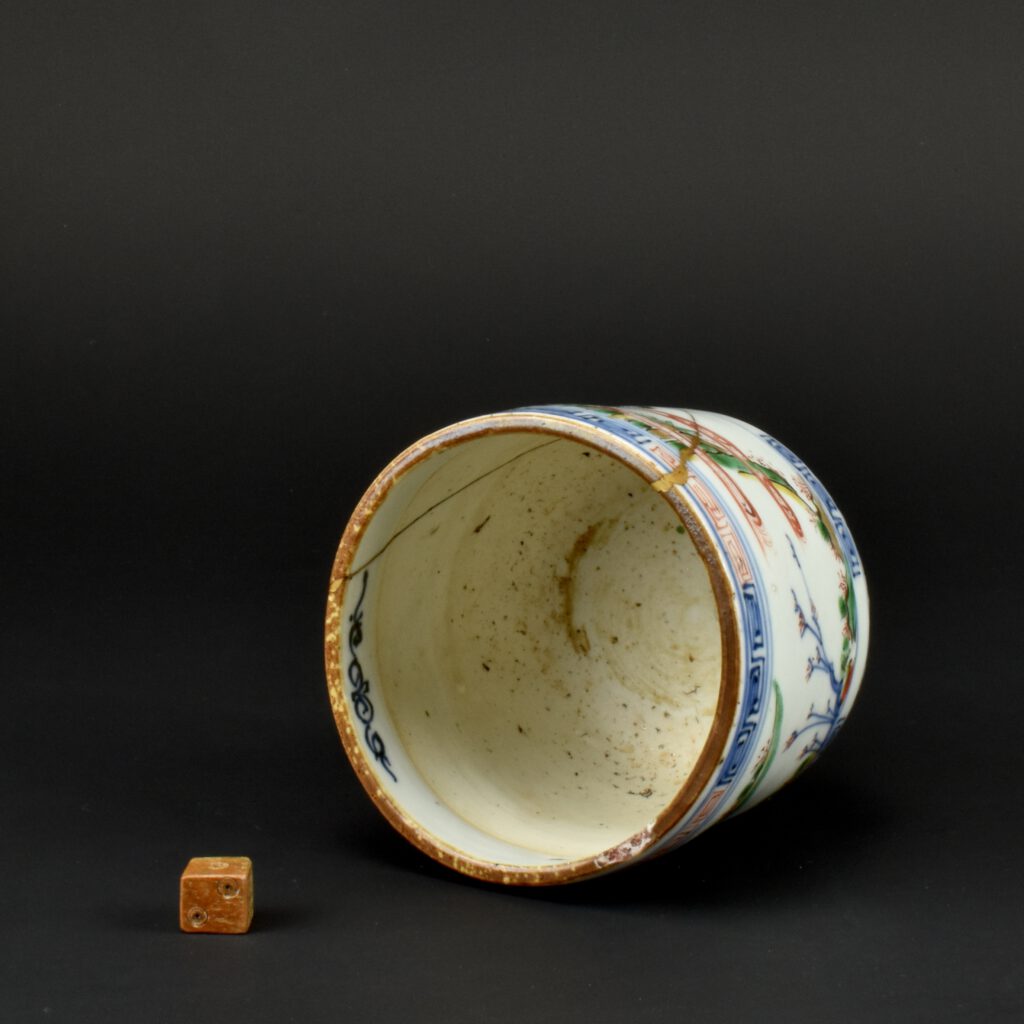

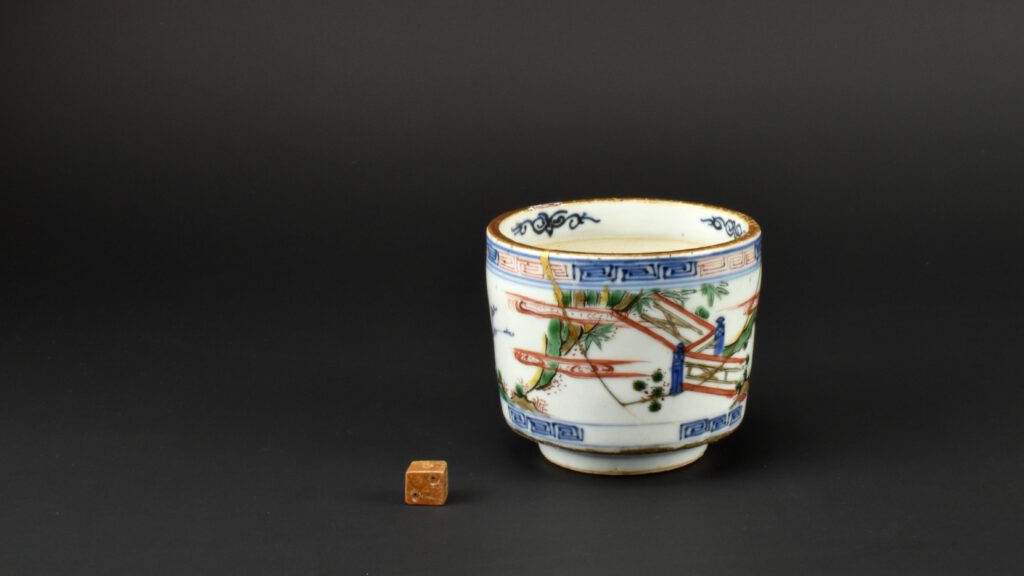

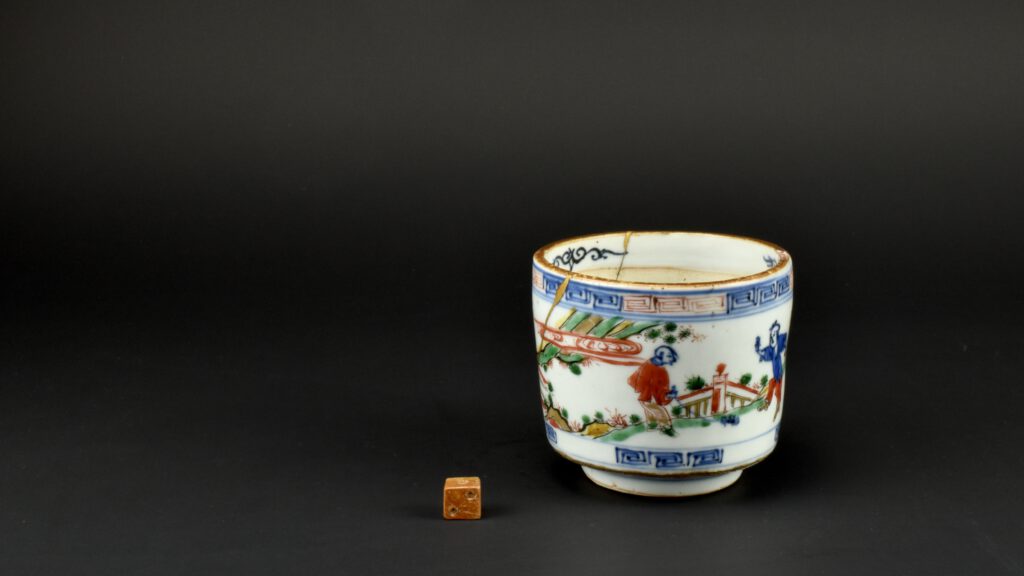

A Rare Ming Ko-akae Porcelain Bowl, Chongzhen Period 1628 – 1644. This bowl was probably used as a Charcoal Container, called Hiire in Japan. Once filled with ash, the container would have held pieces of burning charcoal which could be used to light a pipe. In early 17th century Japan tobacco became fashionable with tea drinker. A charcoal container with Japanese pottery pipes as well as a tray for holding them together with a container for loose tobacco would be placed in the waiting room for use before the tea ceremony. Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591) one of Japan’s leading tea masters was known to have possessed such a bowl, it was probably Japanese pottery as there don’t appear to be extant Chinese charcoal burners from the 16th century. This thickly potted Ming container was made for the Japanese market, it is functional and yet the scene depicted uses a striking colour scheme, under-glaze cobalt blue, dull aubergine, vibrant translucent green, mustard yellow, and a thin flat red with a dense thin black reserved for some of the outlines. The central scene depicts two young boys playing in a balustraded garden, the boy on the right is very active, while the boy on the left is concentrating on a small crab which he is controlling with a cord. This Hiire is unevenly potted, perhaps deliberately bent out of shape. The rim is dressed with a brown iron-oxide rich glaze. There a border of glaze to the interior below the rim with three scrolling motifs in underglaze blue. The interior is unglazed. The base has a ‘shop’ type mark in under-glaze blue. This object has imperfections, unevenness, it also has a Kintsugi repair, which can be translated to ‘golden joinery’. I also suspect, the fritting above the foot has been enamelled with an aubergine coloured. So it fits in with the Japanese sensitivity of Wabi-Sabi. See ‘Information’ below to read about Wabi-sabi and also Kintsugi repair.

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

SOLD

- Condition

- There is are two long cracks from the rim to just above the well of the container.

- Size

- Diameter 13.2 cm and 11.7 cm (5 1/4 and 4 1/2 inches) Height 9.3 cm (3 3/4 inches) The thickness of the rim c.8 mm.

- Provenance

- Bought in Japan.

- Stock number

- 26618

- References

- For two related Ming Porcelain Hiire, from our Sold Archive, see below the Photograph Gallery.

Information

A Related Ming Porcelain Hiire

Robert McPherson Antiques - Sold Archive - 21865-1

Condition

A large firing crack that has extended crack. The body of the piece is slightly misshapen where the firing crack is.

Size

Diameter : 14 cm (5 1/2 inches)

Stock number

21865-1

SOLD

Condition

A large firing crack that has extended crack. The body of the piece is slightly misshapen where the firing crack is.

Size

Diameter : 14 cm (5 1/2 inches)

Stock number

21865-1

Robert McPherson Antiques - Sold Archive - 26203.

Condition

There is are two long cracks from the rim to just above the well of the container.

Size

Diameter 13.2 cm and 11.7 cm (5 1/4 and 4 1/2 inches) Height 9.3 cm (3 3/4 inches) The thickness of the rim c.8 mm.

Stock number

26203

Wabi - Sabi

A literal translation doesn't work well for the Japanese concept known of Wabi-Sabi. We have imprinted in us a sense of permanence connected with the Classical order, symmetry, things being right, perfect, pristine even. We know an Imperial Qing or Sèvres vase is good quality because it tells us so. The material, fine translucent porcelain, is decorated in rich colours, even gold, the surface filled with decoration that wears its wealth in clear public view. It is perfect and perhaps if we own it will get somewhere nearer perfection ourselves. The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi shows us something quite different. Life is imperfect, we are imperfect, the art of life is to live with it. Perhaps, the nearest we get to permanence is the inevitable realisation that transience is part of the ebb and flow of how things are. Nothing is perfect, Wabi-Sabi allows us to see the beauty inherent in imperfection, the rustic and the melancholy. A potter's finger marks on the surface of a pottery bowl, the roughness of a pottery. A ceramic surface can become a landscape in which the eye walks over humble cracks, uneven, faulty, the mind in austere contemplation. Wabi-Sabi can be condensed to 'wisdom in natural simplicity'.

Wabi-Sabi stems from from Zen Buddhist thought, 'The Three Marks of Existence' ; impermanence, suffering and the emptiness or absence of self-nature. These ideas came to Japan from China in the Medieval Period, they have developed over the centuries and have greatly affected Japanese culture. For example the Japanese tea ceremony, which is the embodiment of perfection, uses ceramics which are imperfect. It was not just the pottery made in Japan that needed to have a Wabi-Sabi nature but also the Chinese porcelain made for the Japanese tea ceremony. During the late Ming dynasty the Chinese supplied Japan with porcelain for the tea ceremony, not just for the ceremony itself but for the meal that was taken with it, the Chinese even supplied charcoal burners for them to light their pipes. This Chinese porcelain was made at Jingdezhen to Japanese designs, sent from Japan. The Japanese wanted the Chinese to work against their normal way, they requested firing faults, imperfections and unevenness. The Chinese were sometimes rather too precise in their making of these imperfections, often adding faults carefully and even symmetrically. I imagined they could have thought, 'why do our customers want us to make these things so badly'. Clearly Wabi-Sabi was lost on them.

Kintsugi

Kintsugi, ‘golden joinery’, also known as Kintsukuroi ‘golden repair’ is the Japanese technique of repairing broken pottery with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver or platinum. As a philosophy, it treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise. Lacquerware is a longstanding tradition in Japan, and at some point kintsugi may have been combined with maki-e as a replacement for other ceramic repair techniques. One theory is that kintsugi may have originated when Japanese shogun Ashikaga sent a damaged Chinese tea bowl back to China for repairs in the late 15th century. When it was returned, repaired with ugly metal staples, it may have prompted Japanese craftsmen to look for a more aesthetic means of repair. Collectors became so enamored with the new art that some were accused of deliberately smashing valuable pottery so it could be repaired with the gold seams of kintsugi. Kintsugi became closely associated with ceramic vessels used for chanoyu (Japanese tea ceremony). While the process is associated with Japanese craftsmen, the technique was also applied to ceramic pieces of other origins including China, Vietnam, and Korea.

An Example of Kintsugi Repair

Robert McPherson Antiques Sold Archive 24486

A Rare Korean Buncheong ware pottery Mishima shiooke chawan, 16th or 17th century, from the Ulrich Vollmer Collection. Perhaps made for the Japanese market. This Joseon dynasty (1392-1910) teabowl is wheel-thrown stoneware with stamped, incised and slip-filled decoration and has a pale green-grey glaze. It is extensively repaired using the Kintsugi technique and comes with a wooden box.

Condition

It is extensively repaired using the Kintsugi technique.

Size

Diameter : 9.8cm (4 cm)

Provenance

The Ulrich Vollmer Collection of Japanese Pottery and related objects.

Stock number

24486

References

Published and Exhibited : Momoyama-Keramik Und Ihr Einfluss Auf Die Gegenwart (Various authors, Gurdrun-Esters for the Keramion Foundation, Frechen, Germany, 2011. ISBN 978-3-94005-6-8.) page 33, plate 35.