A Rare Ming Blue and White Porcelain Bowl

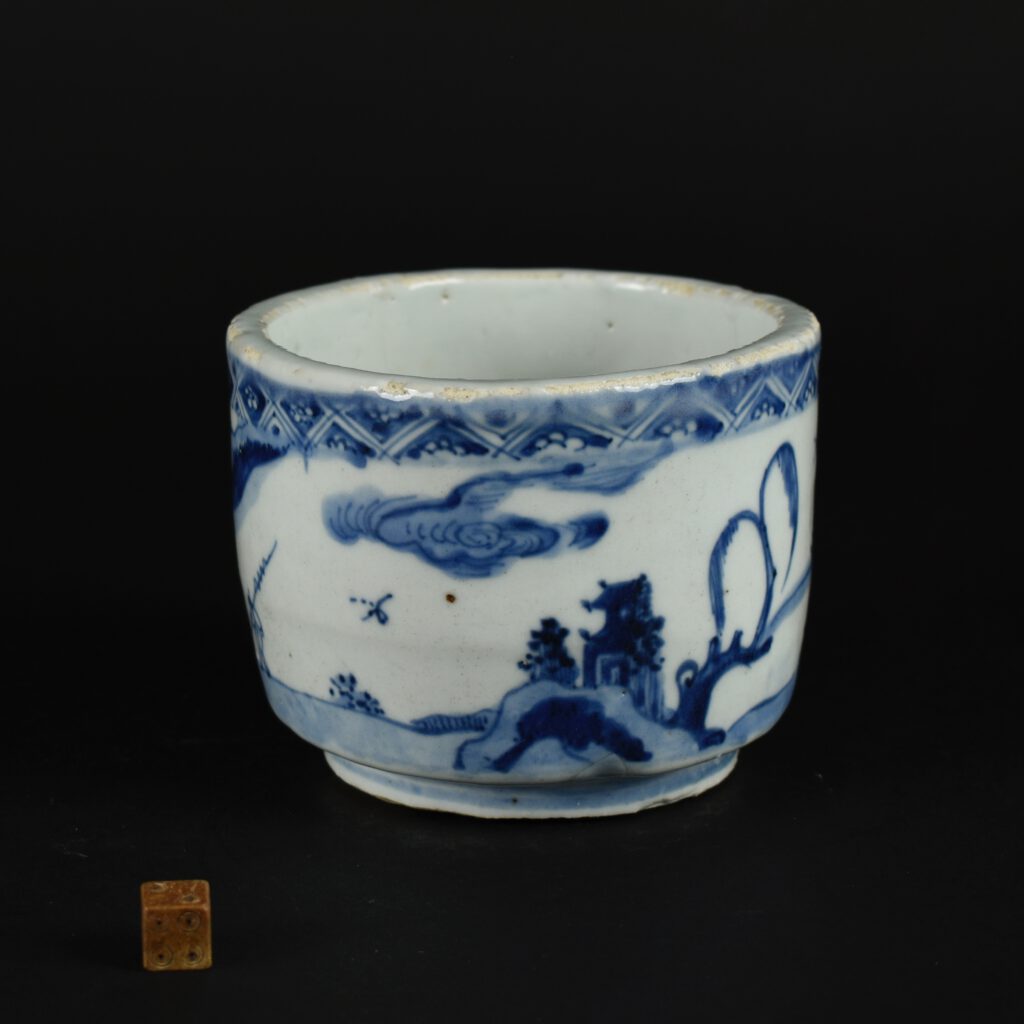

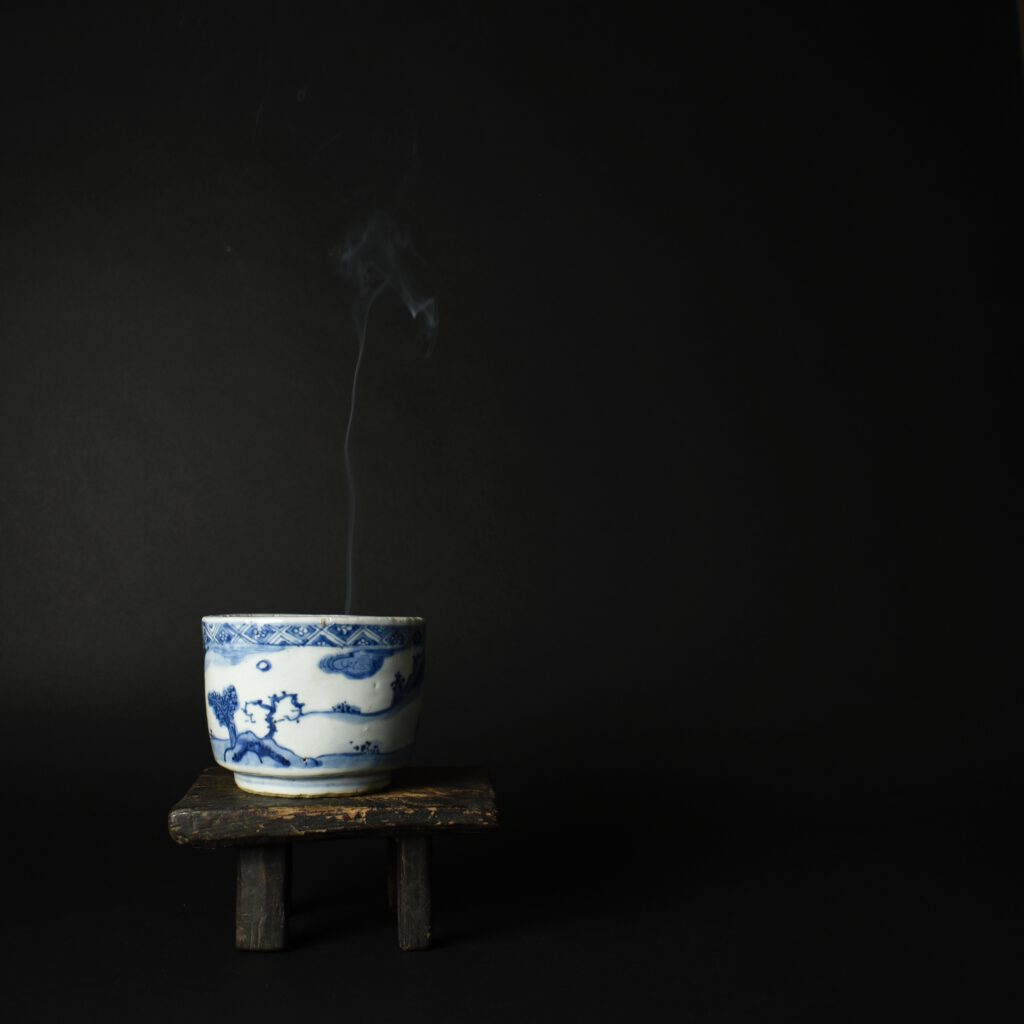

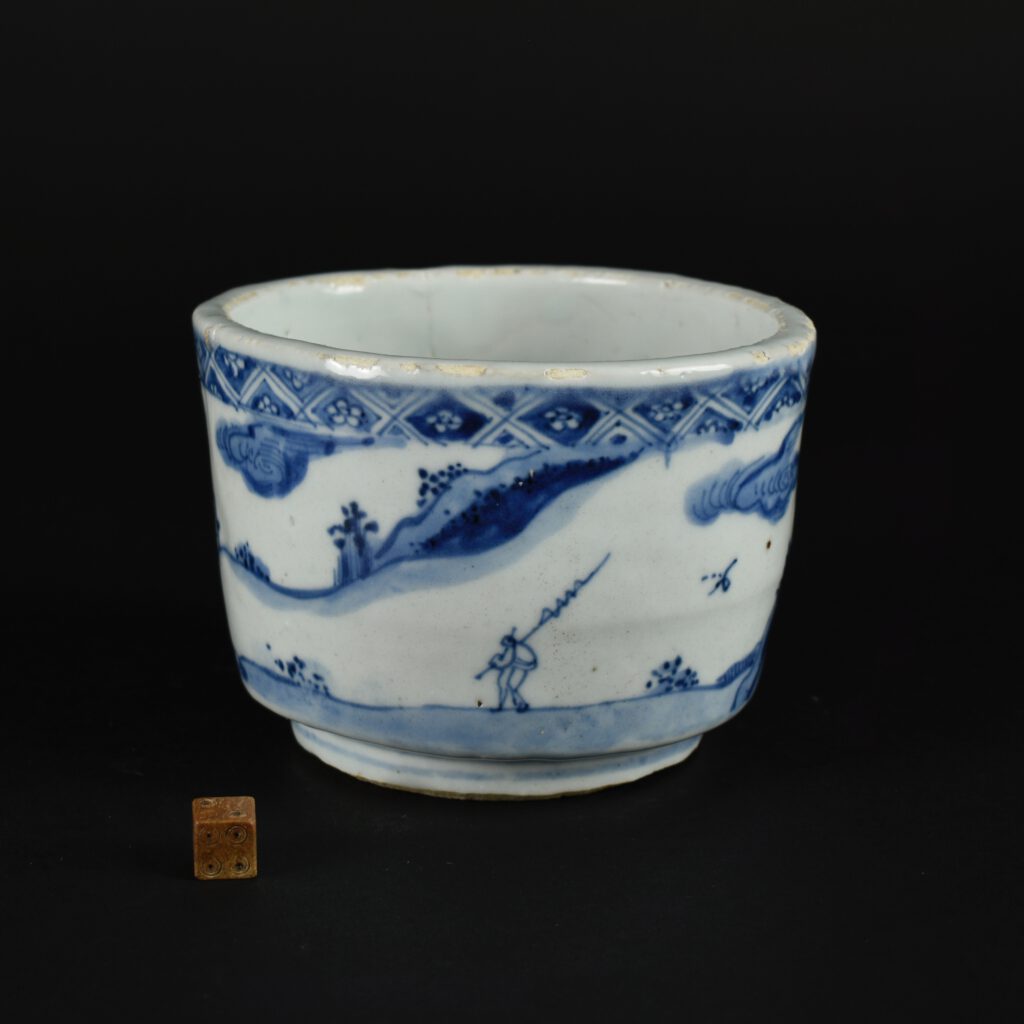

A Rare Ming Blue and White Porcelain Bowl, Tianqi or Chongzhen Period c.1625 – 1640. This bowl was probably used as a Charcoal Container. Once filled with ash, the container would have held pieces of burning charcoal which could be used to light a pipe. In early 17th century Japan tobacco became fashionable with tea drinker. A charcoal container with Japanese pottery pipes as well as a tray for holding them together with a container for loose tobacco would be placed in the waiting room for use before the tea ceremony. Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591) one of Japan’s leading tea masters was known to have possessed such a bowl, it was probably Japanese pottery as there don’t appear to be extant Chinese charcoal burners from the 16th century. This thickly potted Ming container was made for the Japanese market and perfectly reflects Japanese Wabi-Sabi taste – imperfect, humble and desolate (see below). The bowl is uneven, veering towards oval, the rim is heavily fritted, tool marks left by the potter are clearly visible under the thick glaze. A small v-shaped repair appears to have been done by the potter prior to glazing (see close-up photograph). The well is full of kiln grit as well as iron oxide stains. The scene is of a sparse undulating landscape, only populated by two solitary figures, one with a long fishing rod, the other perhaps holding parasol. There is a small building partly obscured by trees or shrubs near a half dead willow tree. The border is in the style of brocaded fabric. Despite being almost oval, this Ming container sits on a circular foot. The Chinese would, I think, have found it curious that the Japanese would order such an odd ‘crude’ bowl. After all they could have made it so much ‘better’ and yet the instructions from Japan would have been to make it imperfect.

SOLD

- Condition

- There is are two long cracks from the rim to just above the well of the container.

- Size

- Diameter 13.2 cm and 11.7 cm (5 1/4 and 4 1/2 inches) Height 9.3 cm (3 3/4 inches) The thickness of the rim c.8 mm.

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 26203

Information

Wabi - Sabi

A literal translation doesn't work well for the Japanese concept known of Wabi-Sabi. We have imprinted in us a sense of permanence connected with the Classical order, symmetry, things being right, perfect, pristine even. We know an Imperial Qing or Sèvres vase is good quality because it tells us so. The material, fine translucent porcelain, is decorated in rich colours, even gold, the surface filled with decoration that wears its wealth in clear public view. It is perfect and perhaps if we own it will get somewhere nearer perfection ourselves. The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi shows us something quite different. Life is imperfect, we are imperfect, the art of life is to live with it. Perhaps, the nearest we get to permanence is the inevitable realisation that transience is part of the ebb and flow of how things are. Nothing is perfect, Wabi-Sabi allows us to see the beauty inherent in imperfection, the rustic and the melancholy. A potter's finger marks on the surface of a pottery bowl, the roughness of a pottery. A ceramic surface can become a landscape in which the eye walks over humble cracks, uneven, faulty, the mind in austere contemplation. Wabi-Sabi can be condensed to 'wisdom in natural simplicity'.

Wabi-Sabi stems from from Zen Buddhist thought, 'The Three Marks of Existence' ; impermanence, suffering and the emptiness or absence of self-nature. These ideas came to Japan from China in the Medieval Period, they have developed over the centuries and have greatly affected Japanese culture. For example the Japanese tea ceremony, which is the embodiment of perfection, uses ceramics which are imperfect. It was not just the pottery made in Japan that needed to have a Wabi-Sabi nature but also the Chinese porcelain made for the Japanese tea ceremony. During the late Ming dynasty the Chinese supplied Japan with porcelain for the tea ceremony, not just for the ceremony itself but for the meal that was taken with it, the Chinese even supplied charcoal burners for them to light their pipes. This Chinese porcelain was made at Jingdezhen to Japanese designs, sent from Japan. The Japanese wanted the Chinese to work against their normal way, they requested firing faults, imperfections and unevenness. The Chinese were sometimes rather too precise in their making of these imperfections, often adding faults carefully and even symmetrically. I imagined they could have thought, 'why do our customers want us to make these things so badly'. Clearly Wabi-Sabi was lost on them.