A Rare Ming Dish from The Peony Pavilion Collection

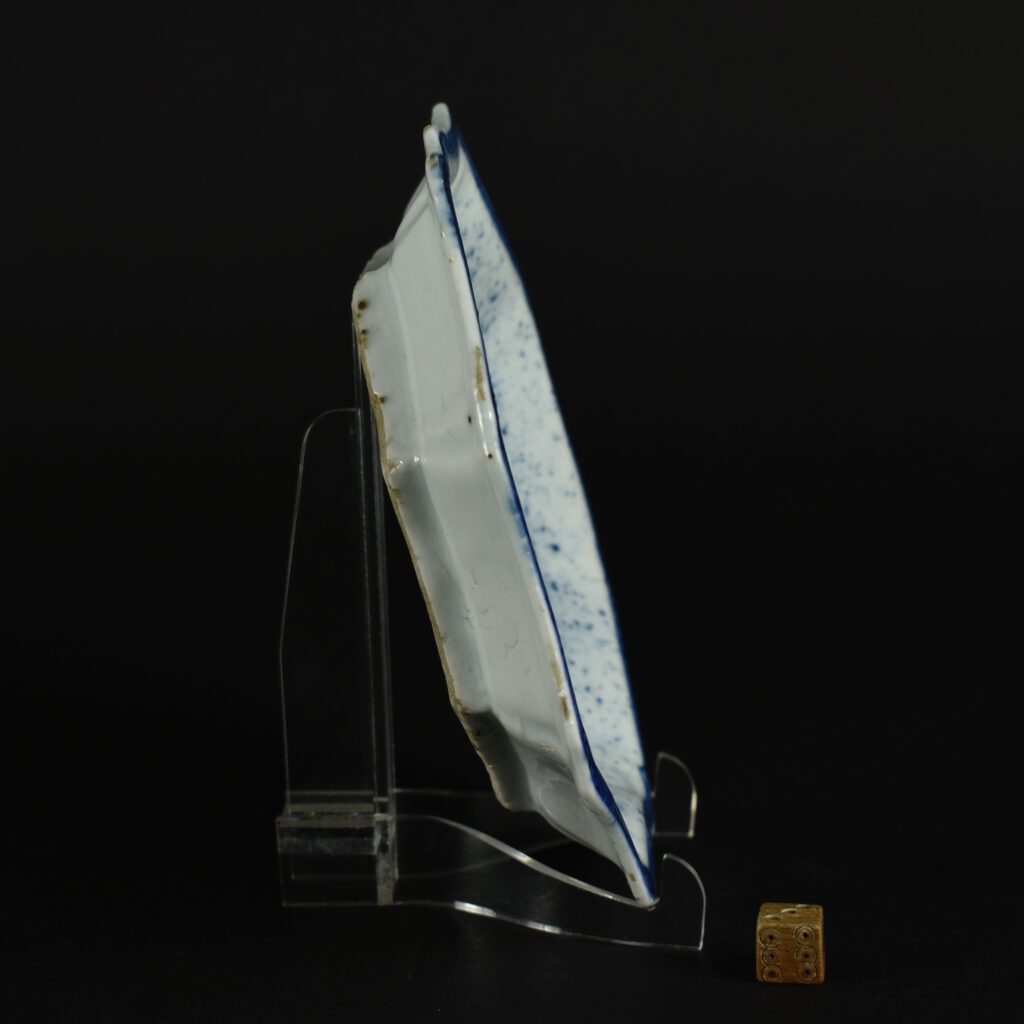

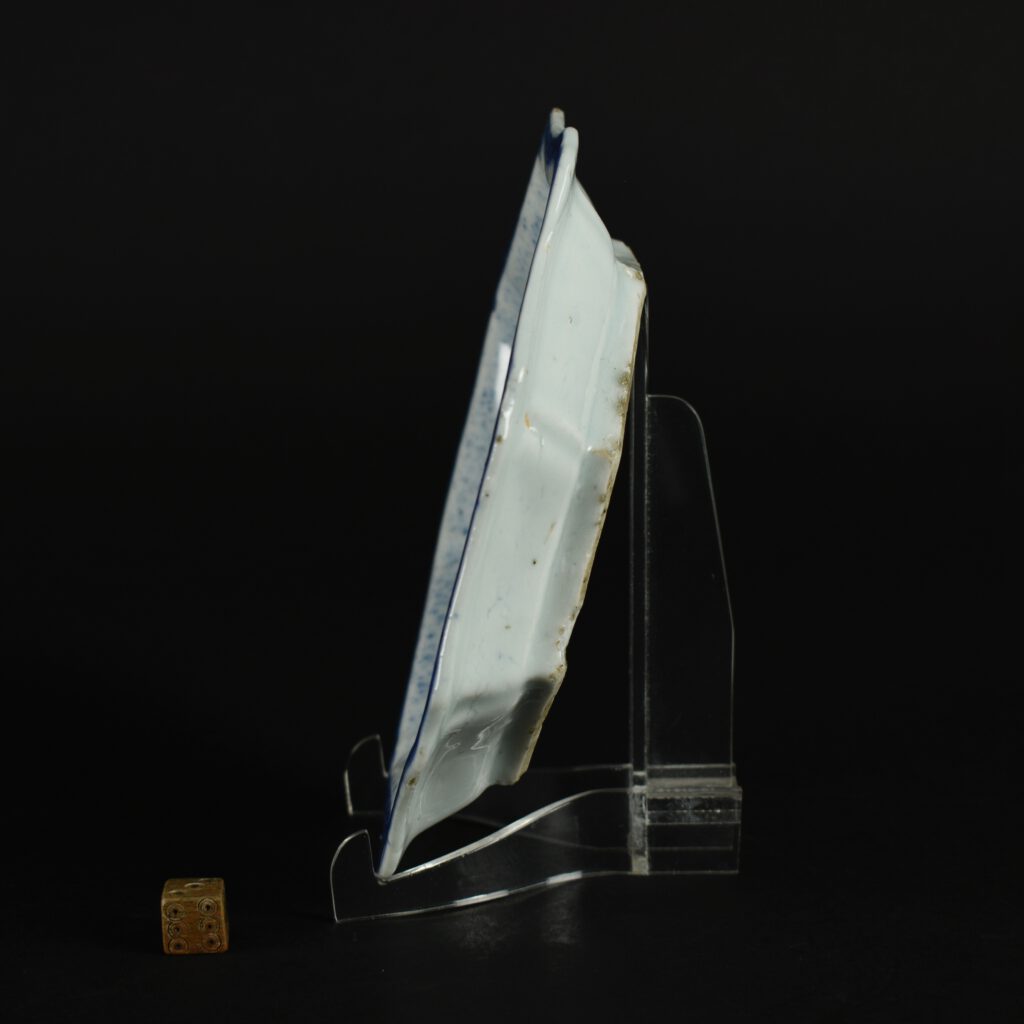

A Rare Ming Spring White Hare Porcelain Dish Made for the Japanese Market. From The Peony Pavilion Collection, Christies 1989, see ‘Provenance’. This late Ming octafoil dish dates from Tianqi or Chongzhen 1621-1644, which is part of the Transitional Period between the Ming and Qing dynasties. The hare, moon, and prunus tree were created with a paper stencil and then covered with Fukizumi (blown ink) and then outlined in cobalt blue after the stencil was removed. In Japan the hare is believed to prepare a food which is the elixir of life. It is possibly that this story, which is adapted from a Chinese, about a hare ponding the elixir of life in a mortar came about because in Chinese ‘full moon and ‘rice cakes’ have the same sound, mochi. With Box.

SOLD

- Condition

- Minor Mushikui frits.

- Size

- Diameter 16.9 cm (6 3/4 inches)

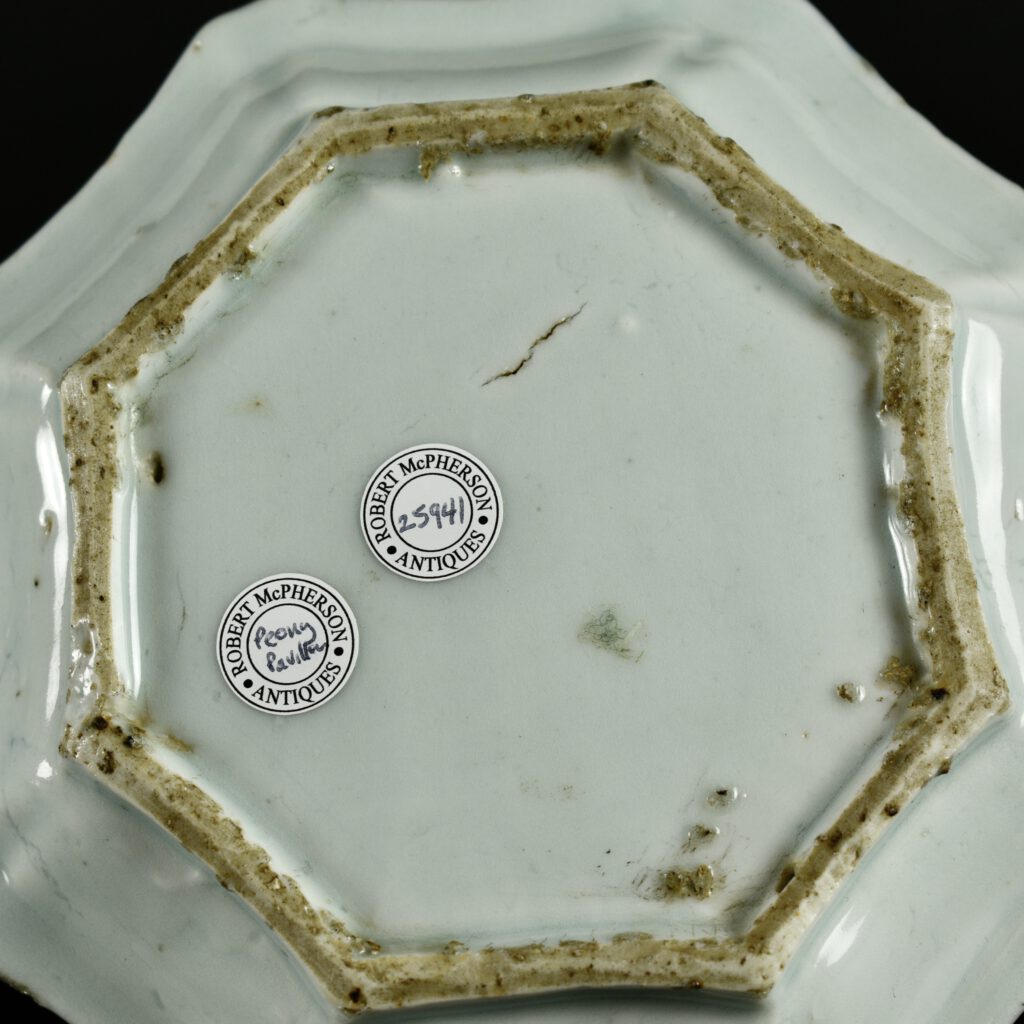

- Provenance

- The Peony Pavilion Collection ; Chinese Tea Ceramics for Japan (c.1580-1650). Christie`s London 12th June 1989, lot 233, sold for £1,980. From a Private Collection, they purchased this lot as well as others. I was able to buy the complete group.

- Stock number

- 25941

- References

- Published : Ko-sometsuke, two volumes by M. Kawahara (published in 1977), monochrome section, page 161, no.634. Published : The Peony Pavilion Collection ; Chinese Tea Ceramics for Japan (c.1580-1650). Christie`s London 12th June 1989, lot 233.

Information

A Japanese Version of this Story, Tengudani kiln, Arita c.1630-1640

A Rare Ko-Imari Porcelain Dish in the Shoki-Imari Style, inscribed ‘Spring White Hare’ within a rectangular cartouche c.1630-1640. This small dish is an excellent example of early Japanese porcelain made at the Tengudani kiln in Arita. The decorative scheme was based on a Chinese prototype but arranged asymmetrically providing a different interpretation using negative space as a design motif. The hare, moon, and cartouche motifs were created with a paper stencil and then covered with blown ink (Fukizumi) and then outlined in cobalt-blue. Similar but somewhat different Hare and Moon dishes have been attributed to the Hiekoba kiln, however these might also be made at the Tengudani kiln. The dishes are different in that the splatter of blue around the design elements are much heavier and constricted to a narrow area around the subject.

The Tengudani kiln might be the earliest of the Arita porcelain kilns (according to Impey). The kilns were excavated between 1965-1970 by a team led by Mikami Tsugio. Five kiln sites were found, in close proximity to or overlaying each other. One of the kilns, referred to as kiln A was given an extinction date of 1614 +/- 12 years. It seems that kilns were active in this area until at least the early 19th century.

Wabi - Sabi

A literal translation doesn't work well for the Japanese concept known of Wabi-Sabi. We have imprinted in us a sense of permanence connected with the Classical order, symmetry, things being right, perfect, pristine even. We know an Imperial Qing or Sèvres vase is good quality because it tells us so. The material, fine translucent porcelain, is decorated in rich colours, even gold, the surface filled with decoration that wears its wealth in clear public view. It is perfect and perhaps if we own it will get somewhere nearer perfection ourselves. The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi shows us something quite different. Life is imperfect, we are imperfect, the art of life is to live with it. Perhaps, the nearest we get to permanence is the inevitable realisation that transience is part of the ebb and flow of how things are. Nothing is perfect, Wabi-Sabi allows us to see the beauty inherent in imperfection, the rustic and the melancholy. A potter's finger marks on the surface of a pottery bowl, the roughness of a pottery. A ceramic surface can become a landscape in which the eye walks over humble cracks, uneven, faulty, the mind in austere contemplation. Wabi-Sabi can be condensed to 'wisdom in natural simplicity'.

Wabi-Sabi stems from from Zen Buddhist thought, 'The Three Marks of Existence' ; impermanence, suffering and the emptiness or absence of self-nature. These ideas came to Japan from China in the Medieval Period, they have developed over the centuries and have greatly affected Japanese culture. For example the Japanese tea ceremony, which is the embodiment of perfection, uses ceramics which are imperfect. It was not just the pottery made in Japan that needed to have a Wabi-Sabi nature but also the Chinese porcelain made for the Japanese tea ceremony. During the late Ming dynasty the Chinese supplied Japan with porcelain for the tea ceremony, not just for the ceremony itself but for the meal that was taken with it, the Chinese even supplied charcoal burners for them to light their pipes. This Chinese porcelain was made at Jingdezhen to Japanese designs, sent from Japan. The Japanese wanted the Chinese to work against their normal way, they requested firing faults, imperfections and unevenness. The Chinese were sometimes rather too precise in their making of these imperfections, often adding faults carefully and even symmetrically. I imagined they could have thought, 'why do our customers want us to make these things so badly'. Clearly Wabi-Sabi was lost on them.