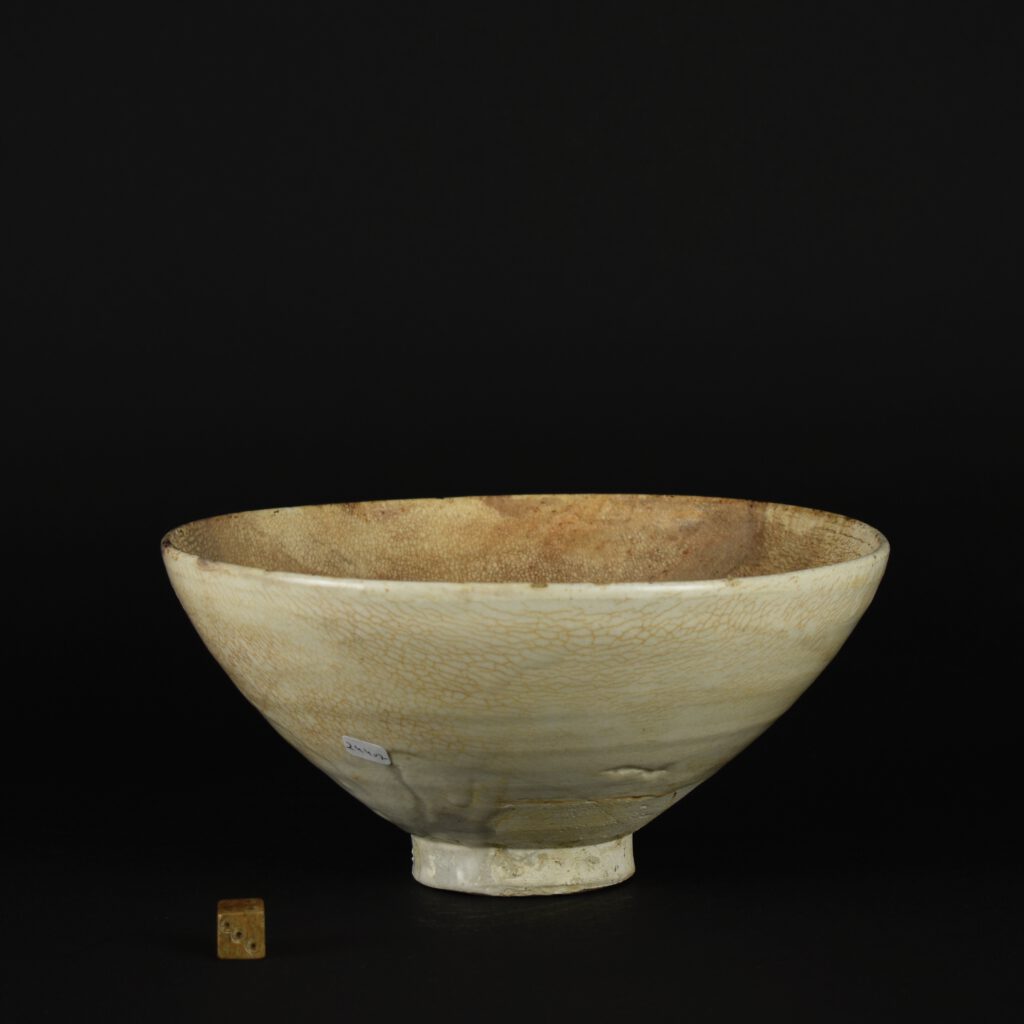

A Song or Yuan Cizhou Bowl

A Song or Yuan Plain White Cizhou Ware Bowl, Northern China, Hebei, Henan, and Shaanxi Province. This elegantly potted Cizhou bowl has a putty coloured body which has been covered in white slip and then glazed, the well of the bowl clearly shows three stilt-marks where the the piece was supported in the kiln. Presumably, this bowl was in close contact with an iron object that corroded releasing iron oxide into the soil and colouring the bowl with this remarkable accidental ‘design’.

SOLD

- Condition

- The piece is extensively stained, there are overlapping layers of deep staining caused by burial. Presumably, this bowl was in close contact with an iron object that corroded releasing iron oxide into the soil and colouring the bowl with a remarkable design. There is some glaze loss to the rim.

- Size

- Diameter 19.6 cm (7 3/4 inches)

- Provenance

- The Florentini Collection, item AC 37. Label to base.

- Stock number

- 24407

Information

Cizhou Ware

A freedom of expression exists in Cizhou ware that is unparalleled by other Song dynasty (960-1279) ceramics. This was a direct result of not being under the control of the court; consequently, the liberty to explore and experiment created an innovative range of designs full of flavour and life unique to Cizhou ware. The utilisation of enamelled decorations in tones of vivid reds, yellows, and greens on occasional Cizhou pieces placed it centuries ahead of its time as this was not kosher for early court wares. The ware also displays an amazing dexterity in the sketchily incised patterns which have such a sense of carefree abandon that they appear impressionistic. Today, Cizhou ware is prized for its natural appearance which often reveals the potter’s process from the wheel’s rings, to the inner spur marks, to the unevenly glazed base.

The white stonewares of the Tang dynasty (618-906) produced two extremely influential wares; the first, Ding ware, became the official ware while the second, Cizhou, became the “popular ware” among the varying classes. It was Cizhou ware’s utilisation by society that assured its continuance during political and dynastic changes which extinguished other Song wares; consequently, Cizhou ware is still produced today though the wares created during the Song dynasty are considered to possess an unrivalled spirit. Since Cizhou ware embodies a diverse range of wares not confined to a specific location, kiln complex, or style it is difficult to precisely define its characteristics.

The name Cizhou originated from the ancient area of Cizhou, encompassing a broad arc across China, which was first recorded during the Sui dynasty (581-618). However, the location constantly shifted and though the area of Cizhou is mentioned in the Tang dynasty (618-906) and Five Dynasties (906-960), each referred to an altered location.During the Song, Jin (1125-1234), Yuan (1279-1368), and partly into the Ming dynasties (1368-1644) the kiln areas of Cizhou were primarily concentrated in the northern provinces of Hebei, Henan, and Shaanxi. (By Mindy MacDonald).

Wabi - Sabi

A literal translation doesn't work well for the Japanese concept known of Wabi-Sabi. We have imprinted in us a sense of permanence connected with the Classical order, symmetry, things being right, perfect, pristine even. We know an Imperial Qing or Sèvres vase is good quality because it tells us so. The material, fine translucent porcelain, is decorated in rich colours, even gold, the surface filled with decoration that wears its wealth in clear public view. It is perfect and perhaps if we own it will get somewhere nearer perfection ourselves. The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi shows us something quite different. Life is imperfect, we are imperfect, the art of life is to live with it. Perhaps, the nearest we get to permanence is the inevitable realisation that transience is part of the ebb and flow of how things are. Nothing is perfect, Wabi-Sabi allows us to see the beauty inherent in imperfection, the rustic and the melancholy. A potter's finger marks on the surface of a pottery bowl, the roughness of a pottery. A ceramic surface can become a landscape in which the eye walks over humble cracks, uneven, faulty, the mind in austere contemplation. Wabi-Sabi can be condensed to 'wisdom in natural simplicity'.

Wabi-Sabi stems from from Zen Buddhist thought, 'The Three Marks of Existence' ; impermanence, suffering and the emptiness or absence of self-nature. These ideas came to Japan from China in the Medieval Period, they have developed over the centuries and have greatly affected Japanese culture. For example the Japanese tea ceremony, which is the embodiment of perfection, uses ceramics which are imperfect. It was not just the pottery made in Japan that needed to have a Wabi-Sabi nature but also the Chinese porcelain made for the Japanese tea ceremony. During the late Ming dynasty the Chinese supplied Japan with porcelain for the tea ceremony, not just for the ceremony itself but for the meal that was taken with it, the Chinese even supplied charcoal burners for them to light their pipes. This Chinese porcelain was made at Jingdezhen to Japanese designs, sent from Japan. The Japanese wanted the Chinese to work against their normal way, they requested firing faults, imperfections and unevenness. The Chinese were sometimes rather too precise in their making of these imperfections, often adding faults carefully and even symmetrically. I imagined they could have thought, 'why do our customers want us to make these things so badly'. Clearly Wabi-Sabi was lost on them.