A Transitional Porcelain Ko-akai Enamelled Dish Made for the Japanese Market

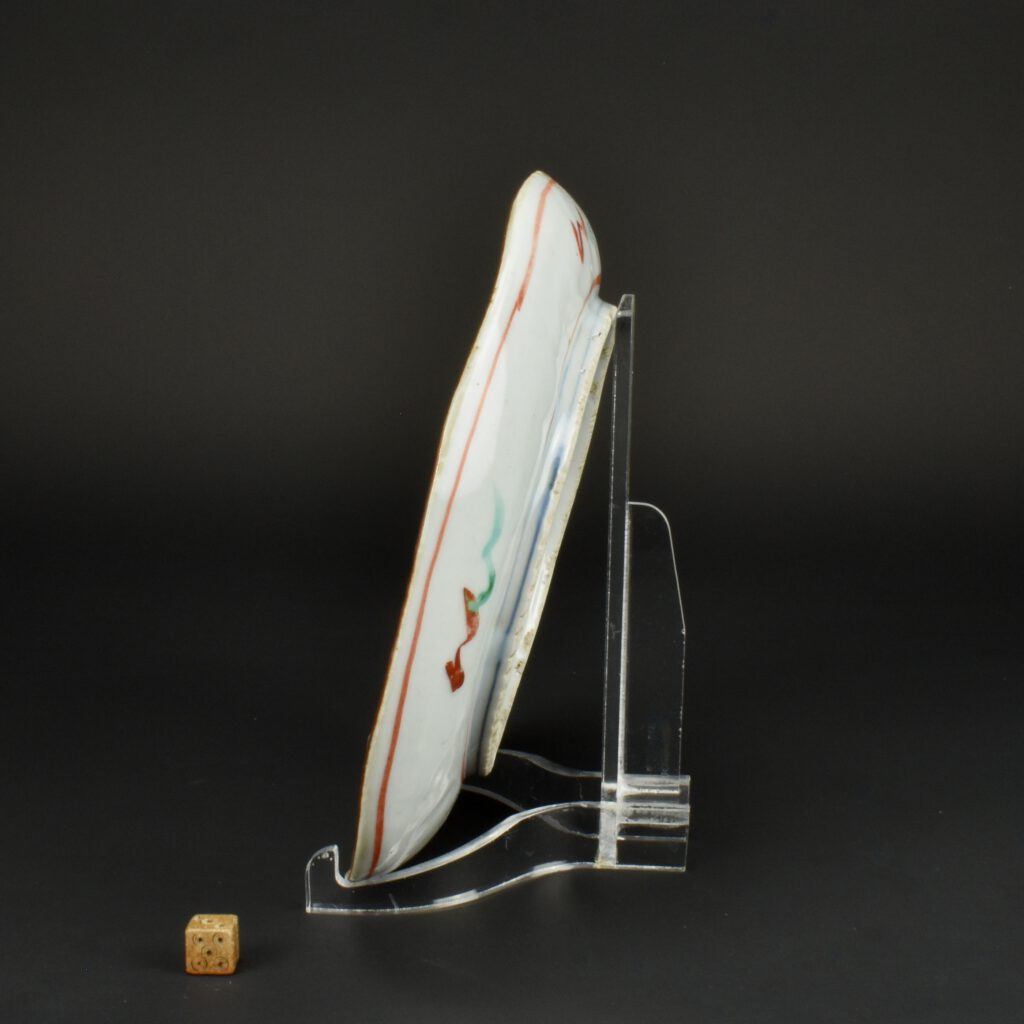

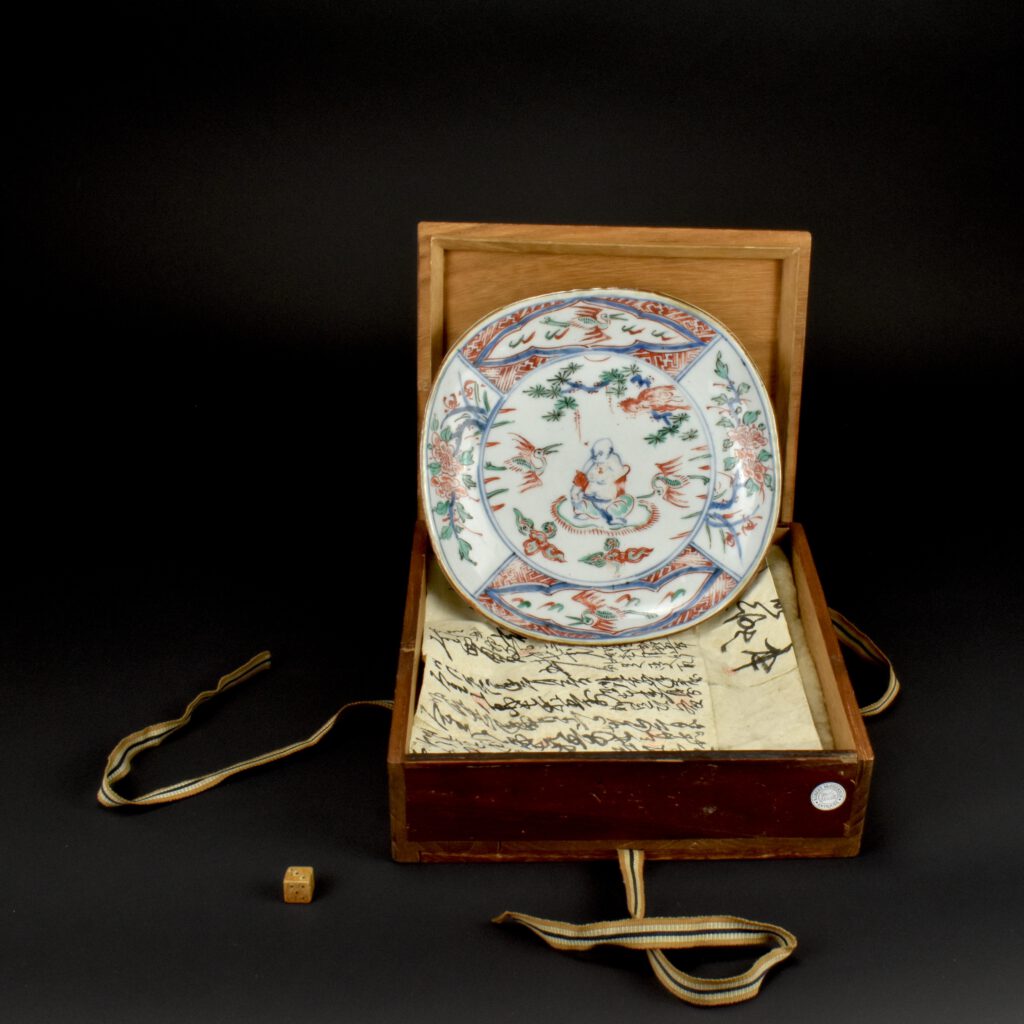

A Transitional Porcelain Ko-akai Enamelled Dish Made for the Japanese Market, Jingdezhen Kilns, Ming Dynasty, Chongzhen Period 1628 – 1644. This Ming dish Ko-akai Ming porcelain is thickly potted and so it is rather heavy. The dish was decorated in underglaze blue and fired, then it was enamelled and given its finial firing. The glaze is blue grey. This serving dish Mukozuke (literally meaning beyond server) was made in for the Kaiseki meal that accompanies the Japanese tea ceremony. Painted in underglaze cobalt blue with green, iron-red, and black. The central scene in the well depicts Budai (Hotei in Japanese), he is a Chinese deity. His name means `Cloth Sack` and comes from the bag that he carries. According to Chinese tradition, Budai was an eccentric Chinese Zen monk who lived during the 10th Century. Bearing in mind the long connection between Zen Buddhism and the Japanese tea ceremony, it is not surprising Budai takes center stage in this design. He sits on a fringed rug with the moon or sun above with pine and a cloud. Two phoenixes flank him, one of which has its head upside down. Below Budai are two ruyi-heads among stylised clouds. The border consists of two facing panels of flowering peony with orchid, the other two facing pales have a cartouche with flying phoenix against a red diaper ground. As with many pieces of Ming porcelain made for the Japanese market, this dish is deliberately made in a way that fits the Wabi-sabi aesthetic of delight in imperfection and accident. The shape is uneven, it is roughly made or should I say made with spirit and energy. The painting is free, there are imperfections such as tiny flecks of the iron red paint left on the surface. The back has allot of kiln grit within the footrim, the rim has been dressed with an iron oxide glaze.

This Ming porcelain comes with a Tomobako box with a piece of Japanese paper with writing and ten red seals. Tomobako storage boxes are an important part of Japanese culture, often made of cedar or paulownia wood. To hold the box and the lid closely together a string is used, which is knotted above the lid in a slipknot (himokake 紐掛け). It was once round, but since the beginning Edo Period (1603-1868) a flat cotton string (sanada-himo 真田紐) is more common. It took me a while to get this right, if you get it wrong it might seem safe but isn’t. Unlike many countries, traditional Japanese buildings had few if any solid walls, so shelves as we know them were not used. Precious objects were kept in boxes for a number of reasons. Western displays with objects on permanent show mean the brain starts to dismiss the objects, they just blend into their environment and become unseen. In Japan, tomobako would be opened among invited friends, they could be looked at with fresh eyes, shared and passed around. A far more down to earth reason is the extreme danger of volcanoes in Japan.

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

SALE PENDING

- Condition

- In very good condition, some minor rubbing. Slight discolouration in places along the edge.

- Size

- Diameter 21.7 cm (8.5 inches).

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 26258

Information

Ko-sometsuke and Ko-akai : Ming Porcelain Made For Japan

Ko-sometsuke is a term used to describe Chinese blue and white porcelain made for Japan, while Ko-akai refers to porcelain decorated with enamels. This late Ming porcelain was made from the Wanli period (1573-1620), through the Tianqi period (1621 - 1627) ending in the Chongzhen period (1628-1644), the main period of production being the 1620'2 and 1630's. This porcelain made in China for Japanese reflected a rise in interest of the Japanese tea ceremony but it also coincided with the beginning of porcelain production in Japan (from c.1610/20). The porcelain objects produced in China were made especially for the Japanese market, both the shapes and the designs were tailored to Japanese taste, the production process too allowed for Japanese aesthetics to be included in the finished object. Its seems firing faults were added, repaired tears in the leather-hard body were too frequent to not, in some cases, be deliberate. These imperfections as well as the fritted Mushikui (insect-nibbled) rims and kiln grit on the footrims all added to the Japanese aesthetic. These imperfections were something to be treasured by the Japanese, they reflect an imperfect world and the aesthetics of Wabi-Sabi. These 'faults' was an anathema to the Chinese but they went along with it to satisfy the needs of their Japanese customers. The shapes created were often expressly made for the Japanese tea ceremony, especially the meal associated with tea drinking, the Kaiseki. Small dishes for serving food at the tea ceremony are the most commonly encountered form. Designs, presumably taken from Japanese drawings sent to China, these are very varied and often extremely imaginative. They often used large amount of the white porcelain contrasting well with the asymmetry of the design, sometime the Chinese couldn't help themselves but to fill in these gaps with 'excess' decoration. Many other forms were made, among them are charcoal burners, water pots, Kōgō (incense box) as well as variously shaped dishes in the form of fish, fruit or familiar country animals.

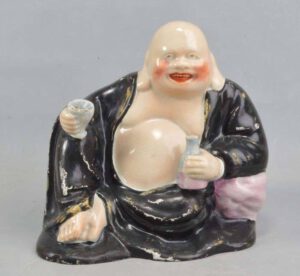

Budai / Hotei / Pagod

Budai (Hotei in Japanese) is a Chinese deity. His name means `Cloth Sack`, and comes from the bag that he carries. According to Chinese tradition, Budai was an eccentric Chinese Zen monk who lived during the 10th Century. He is almost always shown smiling or laughing, hence his nickname in Chinese, the Laughing Buddha. In English speaking countries, he is popularly known also as the `Fat Buddha`. In China Porcelain figures such as the present example would have been used in a family shrine while offering prayers, but in the West they would be seen as exotic curiosities, sometimes referred to as Magot or Pagod. The term Magot was used from as early as the mid 17th century to describe the European heavy set or bizarre representations in clay, plaster, copper or porcelain of Chinese or Indian figures. The term is usually used to describe the European porcelain. Pagoda Figure comes from the term pagode or religious figures housed in pagoda shrines. (Kisluk-Grosheide, `The Reign of Magots and Pagods`, Metropolitan Museum Journal 73, 2002, pp. 177, 181, 182, 184).