An Unusual Ming Ko-Sometsuke Tripod Dish

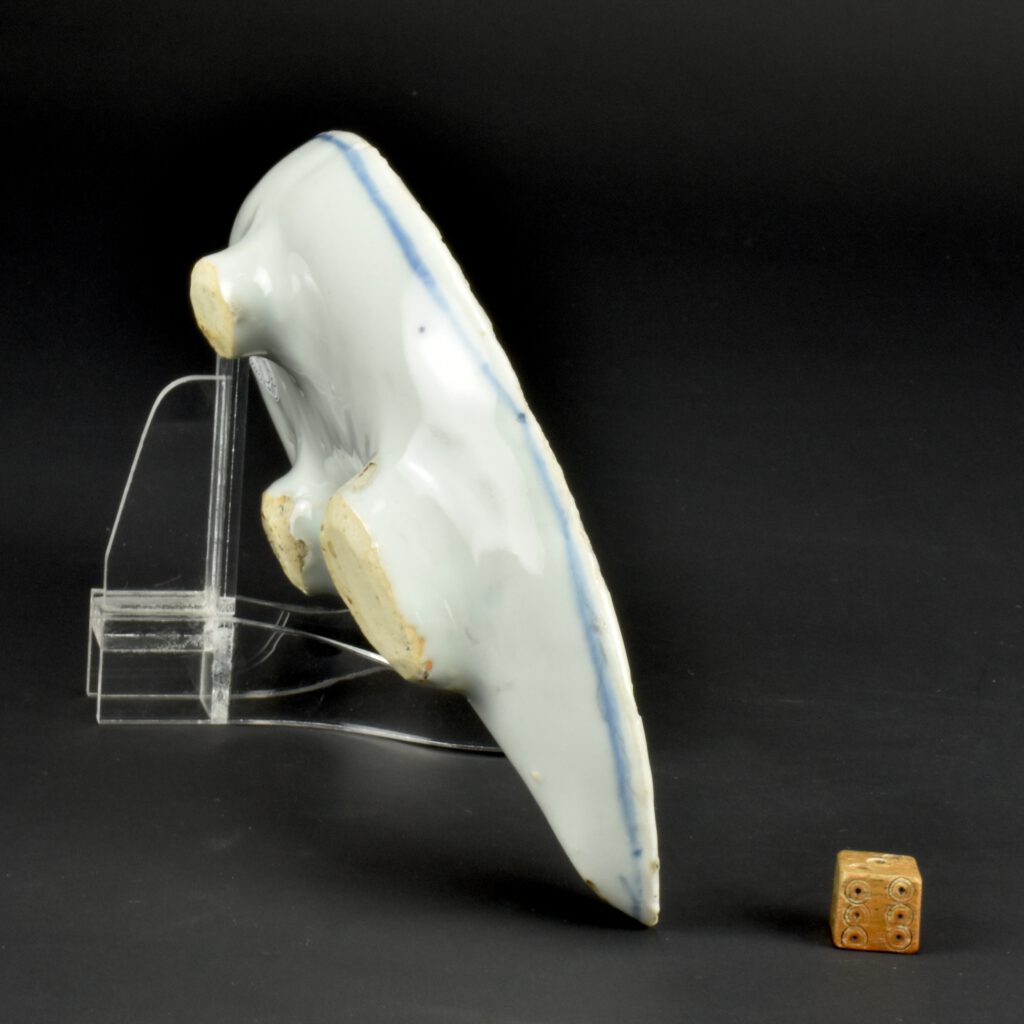

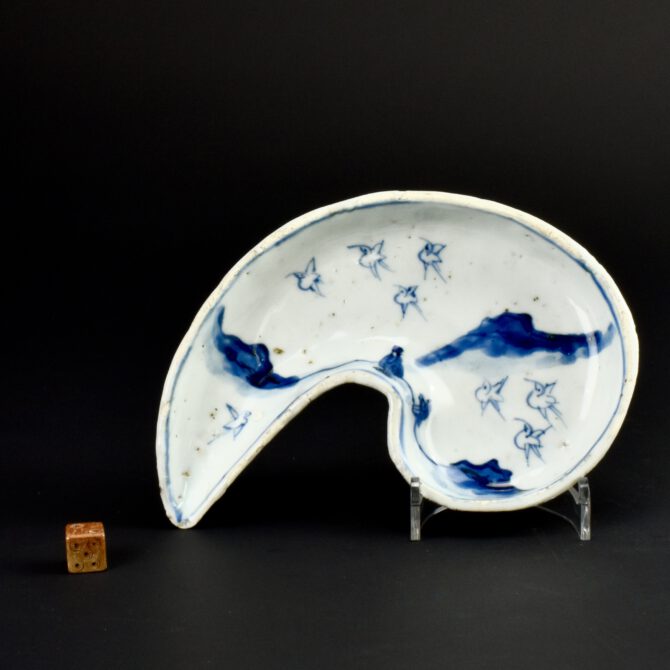

An Unusual Ming Ko-Sometsuke Tripod Dish, Jingdezhen Kilns, Tianqi period (1621 – 1627) or Chongzhen period (1628-1644). The shape is based on a Magatama or a Tomoe, see below for details and illustrations of these comma shaped Japanese designs. This shallow serving dish with raised sides exemplifies the Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi, life is imperfect, we are imperfect, the art of life is to live with it and embrace imperfection, see below for more information. The painting is imperfect, rough even, yet the scene is imbued with life and charm. A mountainous landscape is sketched in with hesitant lines and washes that create a believable landscape. Birds in outline fill the sky, as a lonely scholar and his servant pass by, almost unnoticed. The thick glaze around the rim is uneven, thick and fritted, the surface of the porcelain and glaze are uneven. The glaze has iron-spots, grit and bubbles, these ‘faults’ could have been avoided, but instead, they have been embraced. The three thick rustic feet are of different sizes and shapes, the edges trimmed with a blade.

See Below For More Photographs and Information.

SOLD

- Condition

- Mushikui (insect-nibbled) small rim chips, typical of this Ming porcelain for Japan.

- Size

- Diameter 15.8 cm (6 1/4 inches).

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 26503

Information

Ko-Sometsuke is a term used to describe Chinese blue and white porcelain made for Japan. This late Ming porcelain was made from the Wanli period (1573-1620), through the Tianqi period (1621 - 1627) ending in the Chongzhen period (1628-1644), the main period of production being the 1620'2 and 1630's. This porcelain made in China for Japanese reflected a rise in interest of the Japanese tea ceremony but it also coincided with the beginning of porcelain production in Japan (from c.1610/20). The porcelain objects produced in China were made especially for the Japanese market, both the shapes and the designs were tailored to Japanese taste, the production process too allowed for Japanese aesthetics to be included in the finished object. Its seems firing faults were added, repaired tears in the leather-hard body were too frequent to not, in some cases, be deliberate. These imperfections as well as the fritted Mushikui (insect-nibbled) rims and kiln grit on the footrims all added to the Japanese aesthetic. These imperfections were something to be treasured by the Japanese, they reflect an imperfect world and the aesthetics of Wabi-Sabi. These 'faults' was an anathema to the Chinese but they went along with it to satisfy the needs of their Japanese customers. The shapes created were often expressly made for the Japanese tea ceremony, especially the meal associated with tea drinking, the Kaiseki. Small dishes for serving food at the tea ceremony are the most commonly encountered form. Designs, presumably taken from Japanese drawings sent to China, these are very varied and often extremely imaginative. They often used large amount of the white porcelain contrasting well with the asymmetry of the design, sometime the Chinese couldn't help themselves but to fill in these gaps with 'excess' decoration. Many other forms were made, among them are charcoal burners, water pots, Kōgō (incense box) as well as variously shaped dishes in the form of fish, fruit or familiar country animals.

Magatama

Magatama are curved, beads in similar to a Western comma in shape. They appeared in the Finial Jōmon period (c.1000 B.C.) to the 6th century.

Tomoe

A Tomoe is a coma like swirl, it is used as a symbol and forms part of the heraldic Mon badges and emblems.

Wabi - Sabi A literal translation doesn't work well for the Japanese concept known of Wabi-Sabi. We have imprinted in us a sense of permanence connected with the Classical order, symmetry, things being right, perfect, pristine even. We know an Imperial Qing or Sèvres vase is good quality because it tells us so. The material, fine translucent porcelain, is decorated in rich colours, even gold, the surface filled with decoration that wears its wealth in clear public view. It is perfect and perhaps if we own it will get somewhere nearer perfection ourselves. The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi shows us something quite different. Life is imperfect, we are imperfect, the art of life is to live with it. Perhaps, the nearest we get to permanence is the inevitable realisation that transience is part of the ebb and flow of how things are. Nothing is perfect, Wabi-Sabi allows us to see the beauty inherent in imperfection, the rustic and the melancholy. A potter's finger marks on the surface of a pottery bowl, the roughness of a pottery. A ceramic surface can become a landscape in which the eye walks over humble cracks, uneven, faulty, the mind in austere contemplation. Wabi-Sabi can be condensed to 'wisdom in natural simplicity'.

Wabi-Sabi stems from from Zen Buddhist thought, 'The Three Marks of Existence' ; impermanence, suffering and the emptiness or absence of self-nature. These ideas came to Japan from China in the Medieval Period, they have developed over the centuries and have greatly affected Japanese culture. For example the Japanese tea ceremony, which is the embodiment of perfection, uses ceramics which are imperfect. It was not just the pottery made in Japan that needed to have a Wabi-Sabi nature but also the Chinese porcelain made for the Japanese tea ceremony. During the late Ming dynasty the Chinese supplied Japan with porcelain for the tea ceremony, not just for the ceremony itself but for the meal that was taken with it, the Chinese even supplied charcoal burners for them to light their pipes. This Chinese porcelain was made at Jingdezhen to Japanese designs, sent from Japan. The Japanese wanted the Chinese to work against their normal way, they requested firing faults, imperfections and unevenness. The Chinese were sometimes rather too precise in their making of these imperfections, often adding faults carefully and even symmetrically. I imagined they could have thought, 'why do our customers want us to make these things so badly'. Clearly Wabi-Sabi was lost on them.