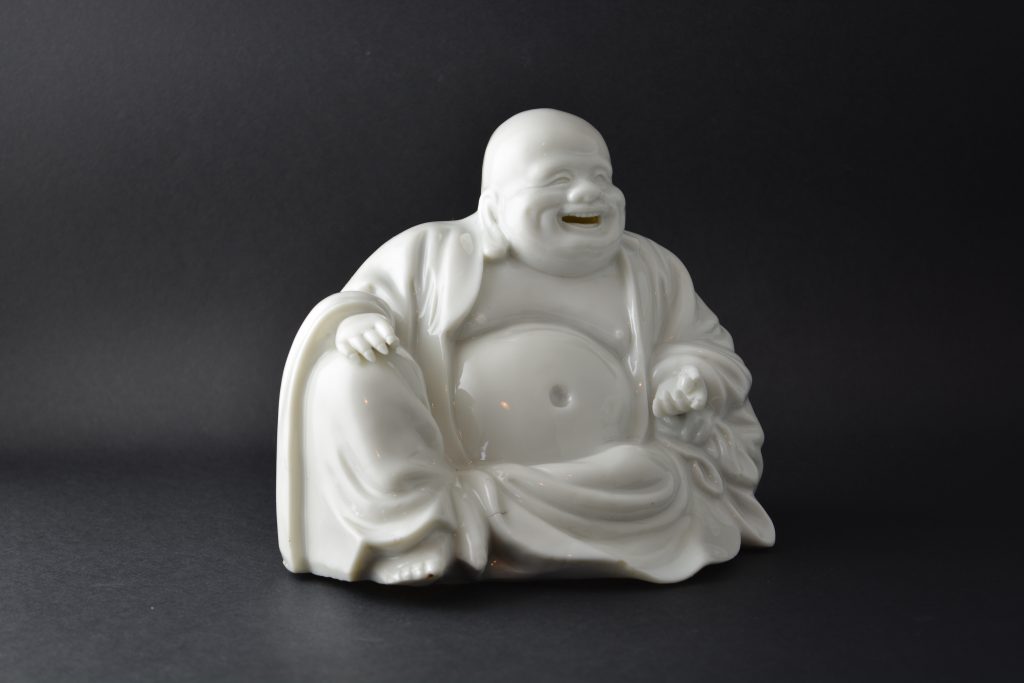

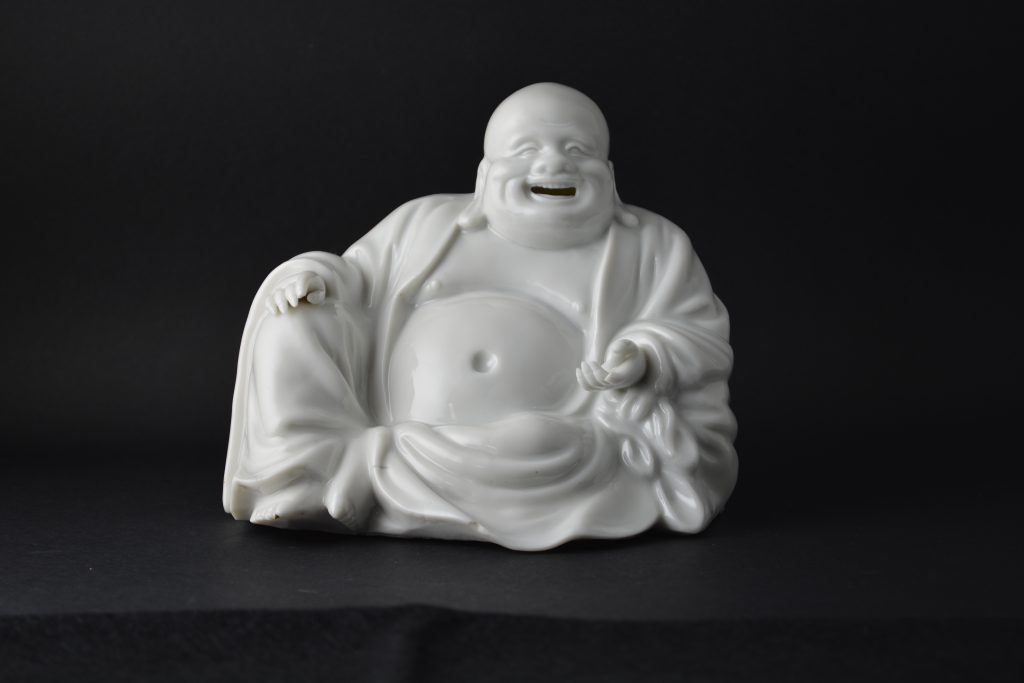

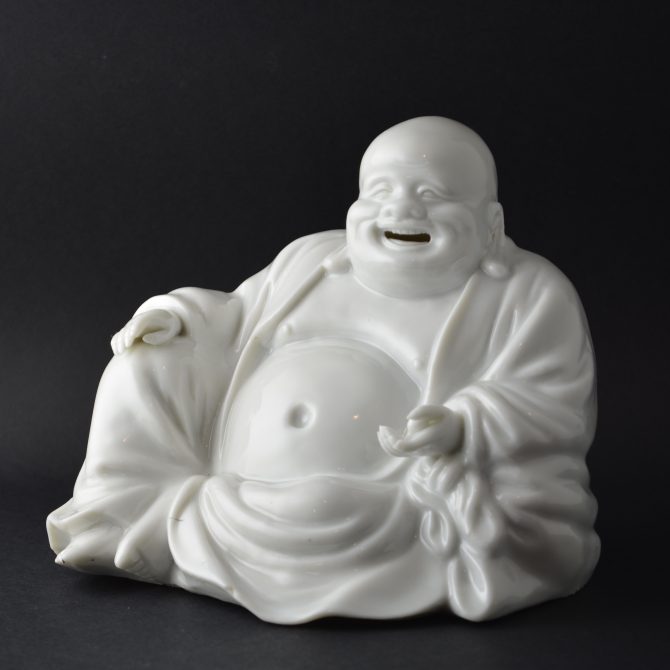

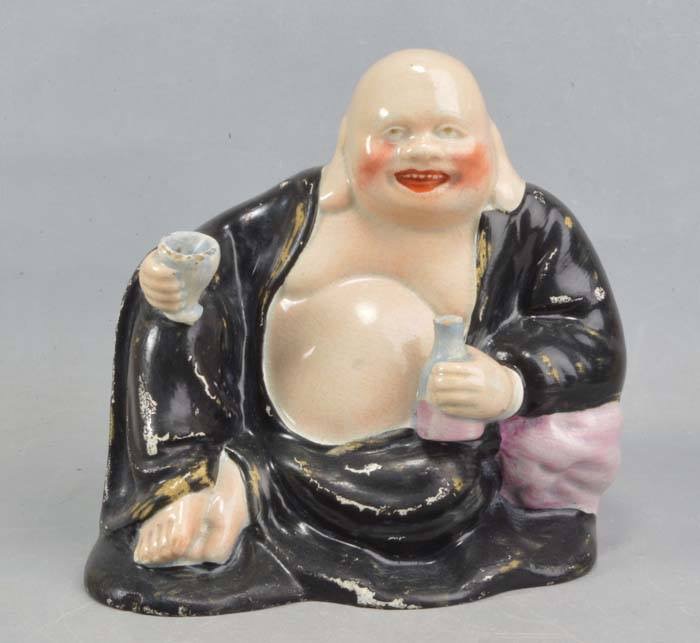

A Kangxi Blanc de Chine Porcelain Model of Budai, 17th Century

A Blanc de Chine porcelain model of Budai, Kangxi period 1662-1722, Dehua kilns, Fujian province. The moulded figure has fine detail, especially the face with the teeth clearly delineated. The body is a rather bright white and the glaze almost colourless.

SOLD

- Condition

- In good condition, chips to the end of Budhai's thumb and forefinger where he holds the pearl and also to his other forefinger. A small chip to his robe at the front lower edge c.5 x 3mm

- Size

- Height : 14.8cm (6 inches). Diameter of the base : 16.8cm (6 1/2 inches).

- Provenance

- N/A

- Stock number

- 25172

- References

- A very similar 17th century model of Budai is Burghley House. Clearly the Chinese significance of Budai was lost, the Inventory of 1688 for the Countess of Exeter in Burghley House lists it thus '(In) My lady's Dressing Roome..... 1 ball'd fryor sitting'.

Information

Blanc de Chine Porcelain :

The porcelain known in the West as Blanc de Chine was produced 300 miles south of the main Chinese kiln complex of Jingdezhen. The term refers to the fine grain white porcelain made at the kilns situated near Dehua in the coastal province of Fujian, these kilns also produced other types of porcelain. A rather freely painted blue and white ware, porcelain with brightly coloured `Swatow` type enamels as well as pieces with a brown iron-rich glaze. However it is the white blanc de Chine wares that have made these kilns famous. The quality and colour achieved by the Dehua potters was partly due to the local porcelain stone, it was unusually pure and was used without kaolin being added. This, combined with a low iron content and other chemical factors within the body as well as the glaze, enabled the potters to produce superb ivory-white porcelain.

Budai / Hotei / Magot / Pagod :

Budai (Hotei in Japanese) is a Chinese deity. His name means `Cloth Sack`, and comes from the bag that he carries. According to Chinese tradition, Budai was an eccentric Chinese Zen monk who lived during the 10th Century. He is almost always shown smiling or laughing, hence his nickname in Chinese, the Laughing Buddha. In English speaking countries, he is popularly known also as the `Fat Buddha`. In China Porcelain figures such as the present example would have been used in a family shrine while offering prayers, but in the West they would be seen as exotic curiosities, sometimes referred to as Magot or Pagod. The term Magot was used from as early as the mid 17th century to describe the European heavy set or bizarre representations in clay, plaster, copper or porcelain of Chinese or Indian figures. The term is usually used to describe the European porcelain. Pagoda Figure comes from the term pagode or religious figures housed in pagoda shrines. (Kisluk-Grosheide, `The Reign of Magots and Pagods`, Metropolitan Museum Journal 73, 2002, pp. 177, 181, 182, 184).

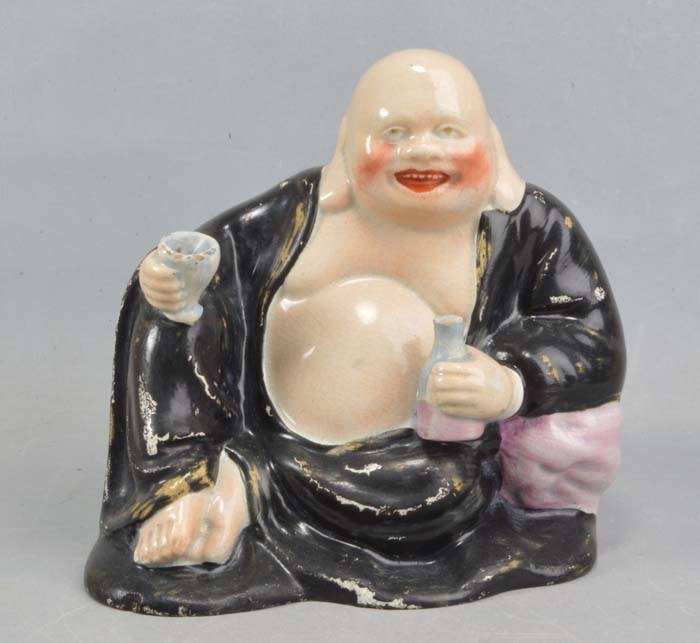

An English version, Staffordshire, early 19th Century