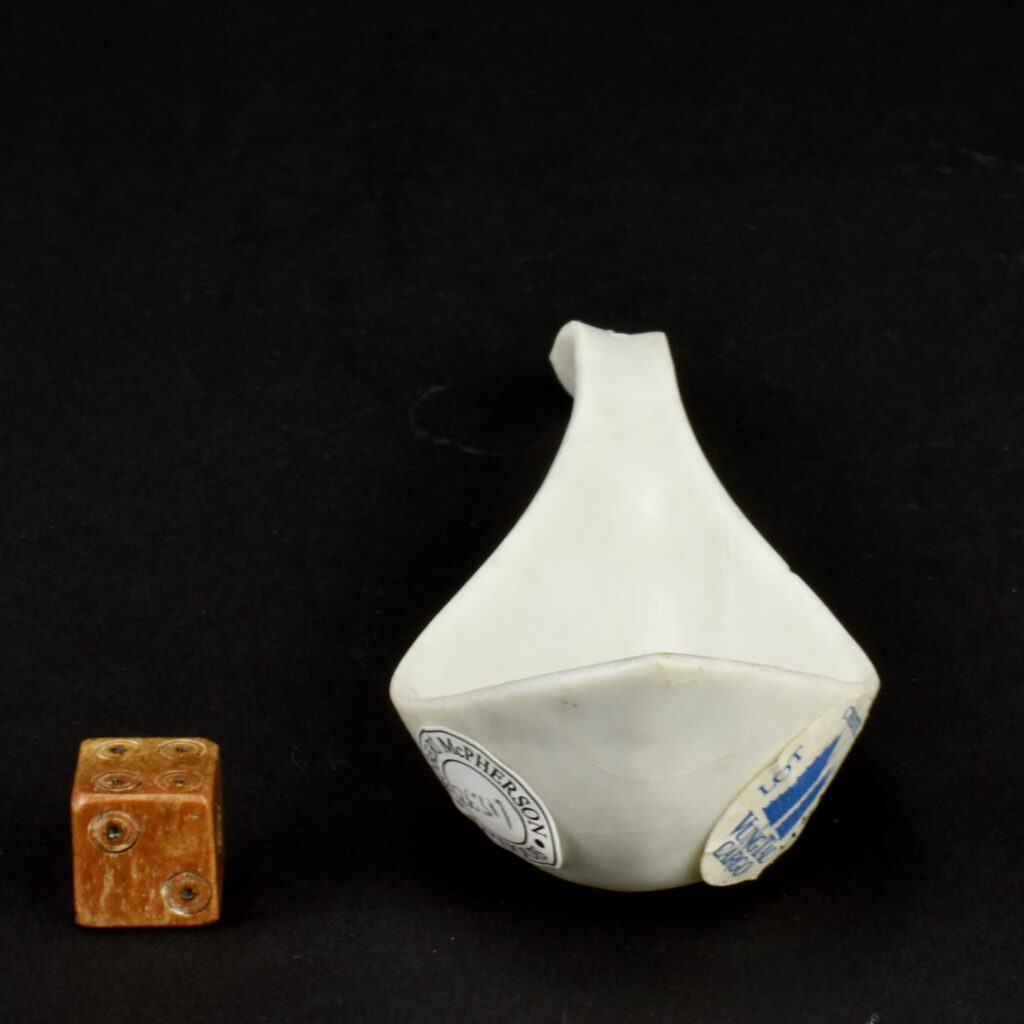

Vung Tau Cargo Blanc de Chine Spoon

A Vung Tau Cargo Blanc de Chine Spoon, Kangxi Period c.1690 – 1700. This thinly potted spoon for eating from a bowl means that form has a deep bowl, the sharp point might serve as something to break up larger pieces of food. The only decoration is a sharply moulded leaf design reminiscent of a Fleur de Lys applied to the terminus. The spoon would have been fired on its base, with the end of the handle supported from underneath. This tradition Chinese form of spoon would have been made for the South East Asian market, including Chinese enclaves within the locality, rather than export to the West. Blanc de Chine in general can be quite difficult to date specifically, a tradition form such as this spoon has remained with little or no change for hundreds of years. Therefore, the provenance of the late 17th century shipwreck is paramount in the dating it to within ten years or so. Without the provenance I would have dated it as Kangxi (1662-1722) accepting that it could be a little later or earlier. Christie’s Vung Tau Cargo label to base lot 461 and a dealers priced at fl.550 (Dutch Florins) .

SOLD

- Condition

- In good condition for shipwreck porcelain. Some slight roughness to the extremities, crazing.

- Size

- Height 12.5cm (5 inches).

- Provenance

- The Vung Tau Cargo, Chinese Export Porcelain. Christies Amsterdam, April 7th and 8th, lot 461 (part lot). An old Dutch label with the price Fl.550.

- Stock number

- 26317

- References

- A Kangxi Blanc de Chine porcelain spoon from the Vung Tau Cargo is illustrated in : Porcelain From The Vung Tau Wreck, The HallStrom Excavation (Christian J.A. Jorg and Michael Fletcher published by Sun Tree Publishing Ltd. ISBN 981-04-5208-X) page 90 Fig.93 . For two Blanc de Chine spoons of this form, also from the Vung Tau Cargo dated to c.1690, see : Exhibition of Blanc de Chine (S. Marchant & Son, June 1994) page 73, items 115 and 115a.

Information

The Vung Tau Cargo :

The Vung Tau wreck was discovered by Vietnamese fishermen and turned into a salvage operation. Some archaeological information was however saved. It was discovered for example that some of the ship’s timbers were badly charred, suggesting that the ship had met with one of the most feared problems that can arise at sea: fire. The Chinese junk was en route to the town of Batavia (present day Jakarta) in Indonesia. Batavia was the centre for the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.). The V.O.C. was the first Dutch company to be funded by shareholders. It began as an attempt to unify the various Dutch companies trading in the East, that were competing against each other. By the late 17th century it had become a massive operation. Central control was supposed to come from Amsterdam, with Batavia and the other bases taking a secondary role. Given the difficult and slow communications and the need to deal with the reality of local practicalities as and when necessary, Batavia tended in practice to adapt or to modify the instructions that had been issued from Amsterdam. Batavia was a large and busy town, built following a Dutch model, complete with a castle, administrative buildings, law courts, churches and a canal. The complex trading relationship the Dutch had with Asia was too involved to describe here in any detail but it is interesting simply to note that Batavia was the most important trans-shipment centre the Dutch had. Goods would arrive from Holland, be traded and oriental goods would be sent back to Holland. About 70% of the Vung Tau cargo was to have been trans-shipped to Holland on an East Indiaman vessel from Batavia. But the Vung Tau junk never reached the Dutch trans-shipment centre. The great interest in Chinese porcelain in England had been prompted by the arrival of Queen Mary from Holland, and the enthusiasm she brought with her for Chinese Blue and White porcelain. Her palaces in Holland, and later in this country, were filled with the Kangxi Blue and White porcelain that she loved so much. Unlike the individual pieces of Blue and White from the period of the Hatcher Cargo (c.1643), the Kangxi porcelain objects from the Vung Tau Cargo were mostly to have been displayed as a collection. The pieces had been made as sets, to be arranged together for impact, and displayed on gilt stands and brackets made for the purpose. These were used to create a rich glittering effect together with garnitures of vases, miniature vases, dishes, and cups and saucers reaching from floor to ceiling. These massed baroque displays have long since been removed from many palaces. However, in Kensington Palace, as part of its restoration, the curators are attempting to replace some of the Kangxi porcelain. Part of the display will include items from the Vung Tau Cargo. Perhaps destined originally for a royal palace, it could be said that the porcelain is finally arriving at its destination – albeit three hundred years or so late! Although some of this cargo might indeed have been intended for a palace, it represented a typical cargo produced for the flourishing Dutch middle and upper class clientèle. A use would have been found too for some of the less purely luxurious and more functional items. Tea, coffee and hot chocolate - newly fashionable beverages - were luxuries that only the wealthy could afford. All three were both exotic and expensive and thus fine porcelain, instead of native European pottery was needed. Many different shapes of blue and white porcelain cups, some with covers, and saucers were included in the cargo.

Blanc de Chine Porcelain From Shipwrecks :

By far the largest category of ceramics found on shipwrecks is blue and white porcelain from the kilns at Jingdezhen. Blanc de chine porcelain is sometimes found among the cargo`s recovered but the majority of cargo`s don`t contain this white porcelain from the Dehua kilns in Fujian province. Because blanc de chine porcelain is so difficult to date pieces recovered from shipwrecks are especially important in establishing a credible chronology. Many blanc de chine forms were used over a very long time, indeed even over hundreds of years, pieces recovered from shipwrecks enable subtle changes that occurred to be attributed to precise periods. The 579 objects recovered from the Hatcher wreck of c.1643 represent the most important group of blanc de chine porcelain found so far. 439 of the pieces were bowls, most of which were made as nests of five, but many other forms are represented including archetypal blanc de chine forms such as censers, a guanyin, trick cups as well as standard forms such as vases. Small models of guanyin were also recovered from the Vung Tau Cargo of 1690 as well as acolytes from larger guanyin figures. There were many bowls, dishes, boxes with covers as well as a few water-droppers. There was white porcelain found on the wreck of the Geldermalsen, however this Nanking Cargo porcelain came from the Jingdezhen kilns and so is not blanc de chine.

Blanc de Chine Porcelain :

The porcelain known in the West as Blanc de Chine was produced 300 miles south of the main Chinese kiln complex of Jingdezhen. The term refers to the fine grain white porcelain made at the kilns situated near Dehua in the coastal province of Fujian, these kilns also produced other types of porcelain. A rather freely painted blue and white ware, porcelain with brightly coloured `Swatow` type enamels as well as pieces with a brown iron-rich glaze. However, it is the white Blanc de Chine wares that have made these kilns famous. The quality and colour achieved by the Dehua potters was partly due to the local porcelain-stone, it was unusually pure and was used without kaolin being added. This, combined with a low iron content and other chemical factors within the body, as well as the glaze, enabled the potters to produce superb ivory-white porcelain. White porcelain was made at the Dehua kilns from early times, some books refer to the white porcelain produced during the Yuan period as being Blanc de Chine, but I think it is not really until the latter stages of the Ming dynasty, during the late 16th century, that a porcelain with clearly recognisable Blanc de Chine characteristics was produced. There is a theory that there was a brake in production during a large part of the 18th century. I am highly sceptical of this, it seams likely that Blanc de Chine porcelain was made all the way through, uninterrupted from the Ming dynasty to the present day.