Early Chinese Ceramics

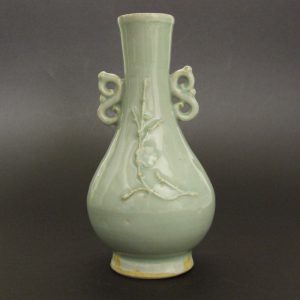

The title of this section is Early Chinese Ceramics, which is perhaps a bit misleading. In fact, these shown here ceramics are relatively late, from about the 9th century to the end of the Ming dynasty in the mid-17th century. Especially when you consider the earliest Chinese ceramics discovered are from the late Palaeolithic period of c.20000 B.C to around 18000 B.C. These low fired earthenware utilitarian objects were discovered in the Xianrendong Cave in South East China. The ceramics here are mostly monochromes, relying on form, colour and texture for their appeal, as well as function. Celadon ware is very well known, it was made in different kilns in the north and in the south of China, it has been made continuously for around two thousand years. Many similar looking ceramics were made made in different parts of China, often at the same period. Details of construction, colour of the clay help with identifying when and where they were made. The odd one out is Blanc de Chine porcelain, which is relatively late, it was made from the 14th century and is still made today. This is a brief look at some types ceramics based on things we have sold. It is by no way comprehensive. Do let us know what you think.

QINGBAI PORCELAIN

One of qingbai’s most distinct features is its transparent icy-blue glaze and the names given to qingbai have attempted to capture the essence of this colour. Qing means ‘bluish green’ and bai means ‘white’ to form the meaning ‘blue white.’ This ware has also been termed yingqing ‘shadow blue,’ yinqing ‘hidden blue,’ and zhaoqing ‘added blue.’[1] The colour was so greatly admired by the Chinese that they often likened qingbai unto their highly prized stone, jade. An exceptional colour of jade referred to as biyu or ‘bluish-white’ exists and is so reminiscent of qingbai that the porcelain was entitled jiayu or ‘imitation jade.’[2]

The earliest known qingbai wares were produced in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province around the late 10th century and are characterized by faint pale-blue glazes on low, wide forms.[3] Qingbai continued to be enormously popular and highly produced throughout the Song dynasty (960-1279) and was prevalent in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), but slackened during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) until being replaced by tianbai, ‘sweet white’ ware.[4] The initial forms of qingbai were simple bowls and dishes, but by the mid-Northern Song the forms had advanced to include a wide variety of objects used for daily life such as ewers, boxes, incense burners, granary models, vases, jars, sculptures, cups, cupstands, water droppers, lamps, grave wares, and tools for writing and painting.[5] The precedent for the majority of these forms is found in earlier metalwork and lacquer and Rawson has suggested that the imitation of silver was the primary force behind the production of white wares, including qingbai.[6].

The body of qingbai is hard, white, and translucent due to its porcelain nature. It is often delicately potted and generally displays an unglazed rim due to its firing in a saggar. The forms tend to be simple as the inhabitants of the Song dynasty valued the aesthetic of a plain well-designed form; however, simple decorations often imitating the designs found on Ding ware began to be incised, combed, and carved onto qingbai. Often, these images portrayed gracefully rendered floral designs which were prominent motifs on Northern Song ceramics. Moulded decoration was introduced during the mid-Northern Song, but became prevalent in the Southern Song when figurative designs of children and animals were popular.

The production of qingbai porcelain has been discovered at numerous kiln sites both north and south of the Yangzi river, in forty-four counties located in nine Chinese provinces.[7] However, it is the kilns of Jingdezhen that have yielded the largest and finest quality of qingbai wares. So far, around Jingdezhen, scholars have estimated that over one hundred thirty six kiln sites can be identified as manufacturing qingbai. The most significant of these sites being found at Hutian, Liujiawan, Nanshijie, Huangnitou, Yangmeiting, Xianghu, and Zhuxi.[8] Additionally, though qingbai ware was produced in enormous quantities for the court and the domestic market it also became a popular trade commodity. This is evidenced by the substantial remains surviving in Southeast Asia, Korea, Japan, South Asia, Africa including Egypt, and the Near East; approximately twenty known countries in Asia, Europe, and Africa received qingbai wares. [9]

After its production peaked the influence of qingbai could still be felt in the two glazes created through the slight alteration of the qingbai glaze’s composition. Thus, the shufu glaze was produced which was more opaque along with the glaze that was to decorate underglaze blue.[10] Furthermore, it is on qingbai ware that the first experimentations with underglaze blue began which eventually developed into one of Jingdezhen’s greatest productions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dated Qingbai Wares of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Hong Kong: Ching Leng Foundation, 1998.

Kai-Yin Lo, ed. Bright as Silver White as Snow: Chinese White Ceramics from Late Tang to Yuan Dynasty. Hong Kong: Yungmingtang, 1998.

Pierson, Stacey, ed. Qingbai Wares: Chinese Porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. London: The Percival David Foundation, 2002.

FOOTNOTES

1Stacey Piers on, ed., Qingbai Wares: Chinese Porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties (London: The Percival David Foundation, 2002), 6-7.

2Ibid., 7.,

3Ibid., 16. This refers to the information published by the Jingdezhen Institute of Ceramic Archaeology 1992, nos. 10, 11.

4Dated Qingbai Wares of the Song and Yuan Dynasties (Hong Kong: Ching Leng Foundation, 1998), 30.

5Ibid., 32.

6Pierson, ed., 19 citing Rawson 1989, 275-301.

7Dated Qingbai Wares of the Song and Yuan Dynasties, 30-36.

8Ibid., 36.

9Pierson, ed., 10-11, referencing Li De-jin, ‘Chinese export porcelain in the VIII-XIV Centuries,’ UNESCO Maritime Route of Silk Roads-Nara Symposium’ 91- Report, Nara International Foundation, Nara, 1993, p. 103.

10Ibid., 12.

DING WARE

In the subsequent Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties (1644-1911) the Chinese so admired the Ding ware produced during the Song dynasty (960-1279) that the court collected it and connoisseurs debated over its inherent beauties.[1] They especially raved over the distinctive ‘tear drops’ that gathered on the outside of Ding ware.[2] Today the influential position Ding ware held is so evident that it is renowned as one of the ‘five famous wares’ of the Song dynasty.

Production of Ding ware began late in the Tang dynasty (618-906) in Quyang county, Hebei province and was closely associated with the finest quality white ware of the Tang dynasty, Xing ware; this was produced in Lingcheng and Neiqui counties, Hebei province about one hundred miles away.[3] Eventually, Ding ware surpassed Xing ware in quality during the Five Dynasties (906-960) an d by the Northern Song dynasty the Ding kilns were producing some of the most successful porcelain available in China; consequently, they were among the first porcelains approved for the court.[4] Interestingly, a fair number of Ding ware display the guan character meaning ‘official’ ware though it was not regularly used in the imperial household; Tsai Mei-fen suggests that this mark may have been placed on imperial tribute wares to separate them from the other wares produced in the kiln.[5]

The popularity of Ding ware continued throughout the Jin dynasty (1125-1234) after the Song court had fled south and left the Ding kilns under Jurchen control. Due to fighting the kilns were temporarily closed, but were reopened and producing court wares at least twelve years into the Jin dynasty.[6] The demand for Ding ware lessened during the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) and eventually, though the historical details are vague, the ware stopped being produced.

At the height of production the Ding kilns created superbly balanced forms with warm ivory coloured bodies of refined porcelain. Often thrown on the wheel these finely potted bodies were shown off through a transparent glaze tinted with a honey brown hue; the hue deepens as it is pools around the finely carved and moulded details. The brown hue was created by the change from a wood burning to a coal burning kiln as the glaze previous to this development had a blue-grey hue. Additionally, with the advancement of a multi-tiered saggar Ding wares were placed on their rims for firing. The bare rim remained unglazed, but was bound in copper or more rarely silver or gold. This addition was not only functional, but a decorative feature as precious metal rims had been added to earlier glazed rims on Ding ware; this type of adornment was so highly valued that the court had a special workshop charged with the decoration of edges on quality wares.[7] Firing on the rim also affected the footring as it no longer had to support the weight of the clay; thus, it became very small, lightweight, and glazed.

Decoration prior to the Five Dynasties period was plain and based on form and colour. However, during the Northern Song extremely fluid designs were carved and incised into Ding ware along with combed detailing. Like qingbai, moulded designs began appearing in the late Northern Song and became prominent in the Southern Song with popular motifs centring around animals, fish, and flowers. Moulding created patterns of thick dense designs that are thought to reflect the contemporary taste for textiles which the factories of Ding-yao produced.

In particular, silk textiles often displayed dense floral patterns similar to the patterns found on moulded Ding ware.[8] Stylistically, it is important to note that though the majority of Ding ware is ivory there is a striking minority decorated in brown, black, green, iron-red, or purplish-brown glazes. Black glaze Ding ware was considered extremely fine as its high glossy shine resembled lacquer which awarded it great prestige; this is emphasized by the fact that traces of gold leaf design have been found on some of these black wares.[9]

The earliest confirmed pieces of Ding ware were discovered in two digong or underground palaces designed as pagodas. Both sites are located fairly close to the Ding kilns in Hebei with the Jingzhi temple dated about 977 and the Jingzhongyuan temple dated about 955. These two pagodas contained a large quantity of ivory Ding ware and have enlightened scholars on the style and quality of Ding ware being produced at that time.[10]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kerr, Rose. Song Dynasty Ceramics. London: V&A Publications, 2004.

Kai-Yin Lo, ed. Bright as Silver White as Snow: Chinese White Ceramics from Late Tang to Yuan Dynasty. Hong Kong: Yungmingtang, 1998.

Liu Liang-yu. A Survey of Chinese Ceramics: Sung Wares. Taipei: Aries Gemini Publishing Ltd, 1991.

Pierson, Stacey and S. F. M. McCausland. Song Ceramics: Objects of Admiration. London: University of London, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art: School of Oriental and African Studies, 2003.

Wood, Nigel. Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation. London: A & C Black, 1999.

FOOTNOTES

1Kai-Yin Lo, ed., Bright as Silver White as Snow: Chinese White Ceramics from Late Tang to Yuan Dynasty (Hong Kong: Yungmingtang, 1998), 19.

2Stacey Pierson and S. F. M. McCausland, Song Ceramics: Objects of Admiration (London: University of London, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art: School of Oriental and African Studies, 2003), 17.

3Nigel Wood, Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation (London: A & C Black, 1999), 100.

4Rose Kerr, Song Dynasty Ceramics (London: V&A Publications, 2004), 44.

5Pierson, 11, referencing Tsai Mei-fen, ‘The Role of the Government in the Development of Ceramics in the Sung Dynasty’, in National Palace Museum, Art and Culture of the Sung Dynasty, 960-1279 (Taipei, 2000), 321-329. So far about fifteen characters have been found on Ding ware, but the guan character is the most common.

6Kerr, 49.

7Ibid., 45, quoted from Ts’ai Mei-fen, ‘A Discussion of Ting Ware with Unglazed Rims and Related Twelfth-century Official Porcelain’, Arts of the Sung and Yuan, ed. Maxwell K. Hearn and Judith G. Smith, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1996), 112-113.

8Liu Liang-yu, 81. Excavation has revealed ceramic shards that combine the patterns found in silk textiles with forms of metalwork to create moulds for porcelain decoration.

WHITE WARE

Since the Tang dynasty (618-906) writers have paid homage to the beauty of white wares leaving tangible evidence of their value. However, the class and refinement displayed in wares of complete whiteness had been sought after hundreds of years before the Tang dynasty and would be cultivated for hundreds of years after its demise. This infatuation generated a variety of white wares which vary in degree of whiteness, refinement of materials, and decoration as a large number of kilns produced white wares even if it was not their specialty. Importantly white wares are not confined to one way of production or from one kiln or geographic area. Until the Southern Song dynasty white wares were considered a product of northern China, however, white wares were still manufactured in the south. Thus, within this commentary, white wares are loosely defined as a body (porcelain or stoneware), slip, glaze, or any combination therein, that creates a white or white-toned ware. Additionally, only a few of the most influential white wares produced during the Song dynasty (960-1279) are discussed as scholars are still debating over the many types of white wares. Future excavation and research hold many exciting discoveries for this discipline.

With white ware it is important to note that though porcelain and stoneware bodies can look different they are essentially the same materials and the borderline between the two can be hazy. Technically, porcelain has a greater refinement to its body and is fired at a higher temperature, however some high quality stonewares have fine white bodies. Interestingly the Chinese only use one word, ci, to describe both porcelain and stoneware bodies.[1]

Pursuit of white wares in northern China had begun by the Shang dynasty (17th-11th century BC) where remains of a few white proto-porcelains exist. Though white in colour these wares were not practical for use as they were soft and porous; however, in a society that primitive they had to have immense aesthetic appeal.[2] Eventually, during the Eastern-Zhou (770-221 BC), the proto-porcelains began to imitate contemporary bronze forms and copy their decorations such as ribbed banding and scroll motifs termed leiwei or ‘thunder pattern.’ Then during the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) the forms became varied and more independent of bronze work alternatively drawing inspiration from lacquer.[3]

Some of the most prominent white ware:

CIZHOU WARE

Production of Cizhou ware began early in the Northern Song Dynasty throughout northern China though higher concentrations are found in Hebei, Shaanxi, Henan, Shanxi, and Shandong provinces.[4] One of the four categories of Cizhou ware produced is a white wear which was predominate in the earliest years of its manufacture. The coarse stoneware body has a grey or buff tone which was coated in an ivory-white slip and transparent glaze. This ware is prized for its natural appearance which reveals the potter’s process from the wheel’s rings, to the inner spur marks, to the unevenly glazed base. The foot and potting tend to be thicker though there is an amazing dexterity to the sketchily incised patterns that have such a sense of carefree abandon that they appear impressionistic. (For more information see the Cizhou reference).

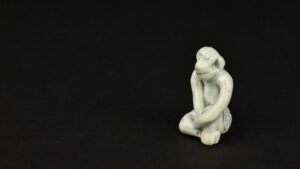

BLANC DE CHINE PORCELAIN

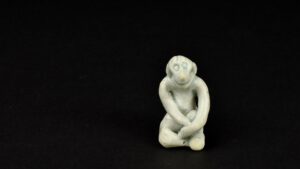

Eventually Dehua ware became one of the best known and collected ceramics in Europe; however, it origins were of very humble means during the late Northern Song Dynasty. Due to the popularity of qingbai on the commercial market, the Dehua kilns started producing wares on a large scale during the Southern Song dynasty. The wares were often white with a bluish tinge, likely in imitation of qingbai, but with a coarser body of chalky white clay; generally, this was pressed into moulds to form objects such as cosmetic boxes and figurines.[5] The Dehua kilns primarily made white wares for export and vast quantities were shipped from the port of Guangzhou.[6] In time, the wares became more refined and the bluish tinge was abandoned for a thick glassy glaze of light-ivory. Production of Dehua wares continued far into the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) with the Dutch East India Company exporting vast quantities to Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries where it became known as the famous blanc de chine ware.[7]

Condition

Repaired, there is an old repair to the back, a large section has been broken out and restuck. Within this section there is a related restuck chip only visible from above. The U-shaped section that has been broken out is 60 x 35 mm. There is a flake chip to the back of the water inlet behind the crab 10 x 10 mm.

Size

Diameter : 14.7 cm (5 3/4 inches).

Stock number

25045

References

For a very similar Blanc de Chine porcelain water dropper dated to c.1640 see : Exhibition of Blanc de Chine (S.Marchant & Son, London, 1985) plate 33, offered for sale at £2,000. For a further Blanc de Chine water dropper dated as Ming c.1640 see : Exhibition of Blanc de Chine (Marchant, London, 2014. ISBN 978-0-9568400-7-3) page 96, plate 72. Offered or sale at £12,000.

Ding

Production of Ding ware began late in the Tang dynasty in Quyang county, Hebei province and was closely associated with Xing ware. During the Five Dynasties (906-960) Ding ware developed into its own distinct style and by the Northern Song dynasty the Ding kilns were producing some of the most successful porcelains in China.[8] Ding ware is characterized by its ivory coloured body, clear honey-brown glaze, copper bound rim, and “tear drops” which run down the outside of its wares. Decoration of Northern Song Ding ware was typified by elegant hand carved and incised designs with combed detailing; this contrasts with Southern Song Ding ware which tended to display densely moulded motifs. Due to Ding’s popularity many kilns produced their own version of the wares which are termed Ding-type wares; however, these wares differ in refinement of body and craftsmanship to those produced at the Ding kilns. (For more information see the Ding reference)

Gongxian

The Gongxian kilns in the Henan province are closely linked to the Xing kilns about three hundred fifty miles north. The Gongxian kilns began producing white ware in imitation of Xing ware during the Tang dynasty. However, the Gongxian body was coarser and coated in a clear yellow or greenish-tinged glaze. During the Song dynasty Xing and Gongxian wares looked similar though as Nigel Wood explains this likeness is only surface deep as Xing ware was fired at a high temperature and often had an added layer of white slip enhancing its whiteness. These measures were not used on Gongxian ware which tended to have a creamier appearance.[10] (A lot of information is still being gathered on this ware.)

Qingbai

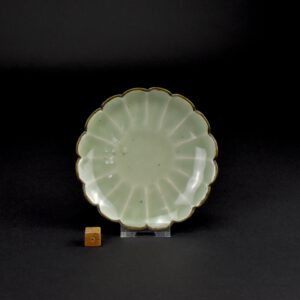

Qingbai wares were being produced in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province around the late 10th century and they flourished throughout the Song and Yuan dynasties (1279-1368). The initial forms of qingbai were simple A Southern Song Qingbai Porcelain ‘Twin Fish’ Dish 12th or 13th Century. 24727bowls and dishes, but by the mid-Northern Song the forms had advanced to include a wide variety of objects used for daily life such as ewers, boxes, incense burners, granary models, vases, jars, sculptures, cups, cupstands, water droppers, lamps, grave wares, and tools for writing and painting.[11] Qingbai is a white bodied porcelain characterized by an icy-blue glaze that sits on top of the body, it is often delicately potted and generally displays an unglazed rim. The forms are often plain though carved, incised and moulded decorations become fashionable on qingbai during the Song dynasty. Eventually qingbai was replaced by tianbai, ‘sweet white’ ware during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).[12] (For more information see the qingbai reference)

In describing Xing ware the Tang dynasty poet Lu Yu likened it to the colour of snow and the texture of silver.[13]

The Xing kilns in Lingcheng and Neiqui counties in the Hebei province during the Tang Dynasty produced an extremely refined ware of the greatest whiteness that was fired at a high temperature; thus, Xing ware is celebrated as the first true porcelain.[14] Its body is hard and translucent in areas with a slightly blue-tinge colouring its white glaze.

Xing ware was often fashioned after metalwork illustrated in its sharp edges, shiny surface, and thinner potting.[15] It was extremely popular and dominated the market until the Five Dynasties period when Ding ware replaced it as the most prominent white ware. Still, as technology advanced during the Song dynasty wood burning kilns were replaced with coal burning kilns which allowed for a clear glaze to display the full whiteness of the ware. It was during this time that the fame of Xing ware spread abroad and large quantities were exported throughout East Asia, the Middle East, South-East Asia, and North Africa.[16] Xing wares are often found in tombs dating from AD 800-1000 and sometimes have the character ying or ‘full’ on their bases.[17]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chinese and South-East Asian White Ware Found in the Philippines. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Dated Qingbai Wares of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Hong Kong: Ching Leng Foundation, 1998.

Kai-Yin Lo, ed. Bright as Silver White as Snow: Chinese White Ceramics from Late Tang to Yuan Dynasty. Hong Kong: Yungmingtang, 1998.

Kerr, Rose. Song Dynasty Ceramics. London: V&A Publications, 2004.

Krahl, Regina. Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection. Vol. 1. London: Azimuth Editions, 1994.

Wood, Nigel. Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation. London: A & C Black, 1999.

FOOTNOTES

1Kai-Yin Lo, ed., Bright as Silver White as Snow: Chinese White Ceramics from Late Tang to Yuan Dynasty (Hong Kong: Yungmingtang, 1998), 14.

2Kai-Yin Lo, 13.

3Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, vol. 1, (London: Azimuth Editions, 1994), 87.

4Krahl, 260.

5Ibid., 288.

6Chinese and South-East Asian White Ware Found in the Philippines (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1993), 22- 24.

7Ibid., 10-11.

8Rose Kerr, Song Dynasty Ceramics (London: V&A Publications, 2004), 44.

9Kai-Yin Lo, 15.

10Nigel Wood, Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation (London: A & C Black, 1999), 98-99.

11Dated Qingbai Wares of the Song and Yuan Dynasties (Hong Kong: Ching Leng Foundation, 1998), 32.

12Ibid., 30.

13Kai-Yin Lo, 16.

14Kerr, 40.

15Krahl, 120.

16Kerr, 40.

17Chinese and South-East Asian White Ware Found in the Philippines, 3.

CIZHOU WARE

A freedom of expression exists in Cizhou ware that is unparalleled by other Song dynasty (960-1279) ceramics.

This was a direct result of not being under the control of the court; consequently, the liberty to explore and experiment created an innovative range of designs full of flavour and life unique to Cizhou ware. The utilization of enamelled decorations in tones of vivid reds, yellows, and greens on occasional Cizhou pieces placed it centuries ahead of its time as this was not kosher for early court wares.[1] The ware also displays an amazing dexterity in the sketchily incised patterns which have such a sense of carefree abandon that they appear impressionistic. Today, Cizhou ware is prized for its natural appearance which often reveals the potter’s process from the wheel’s rings, to the inner spur marks, to the unevenly glazed base.

The white stonewares of the Tang dynasty (618-906) produced two extremely influential wares; the first, Ding ware, became the official ware while the second, Cizhou, became the “popular ware” among the varying classes.[2] It was Cizhou ware’s utilization by society that assured its continuance during political and dynastic changes which extinguished other Song wares; consequently, Cizhou ware is still produced today though the wares created during the Song dynasty are considered to possess an unrivaled spirit. Since Cizhou ware embodies a diverse range of wares not confined to a specific location, kiln complex, or style it is difficult to precisely define its characteristics.

The name Cizhou originated from the ancient area of Cizhou, encompassing a broad arc across China, which was first recorded during the Sui dynasty (581-618). However, the location constantly shifted and though the area of Cizhou is mentioned in the Tang dynasty (618-906) and Five Dynasties (906-960), each referred to an altered location.[3] During the Song, Jin (1125-1234), Yuan (1279-1368), and partly into the Ming dynasties (1368-1644) the kiln areas of Cizhou were primarily concentrated in the northern provinces of Hebei, Henan, and Shaanxi.[4]

Cizhou forms were particularly fashioned for household use with the most common objects being storage jars, bottles, and pillows though the rarer forms for tableware like ewers, bowls, and cups do exist.[5] Pillows were a specialty of Cizhou ware and often display a rich variety of decoration with subjects such as children, poems, water lilies, and animals. Some of these wares bear a name mark and archaeological evidence has revealed that there were at least four workshops exclusively devoted to this enterprise; the pillows from the “Chang family” workshop continued for the longest duration.[6] The earliest pieces of Cizhou ware are decorated in white slip and a large concentration of this ware is found at Juluxian. From this simple exterior evolved decorations which encompassed a multitude of designs, colours, and techniques.

It has been calculated that over thirty distinct types of decoration exist on Cizhou ware from the Song and Jin dynasties alone.[7] Though a variety of decorations abound, the majority are carved, stamped, incised, or painted. Incising eventually developed into graffito, a common technique on Cizhou ware, in which a layer of slip is carved away to reveal the contrasting colour of the body or another layer of slip beneath the first.[8] Painted designs frequently depict birds or flowers though a number of jars and bottles display calligraphy generally denoting their function as wine containers.[9] Additionally, it is important to recognize Cizhou-type ware which was produced alongside Cizhou ware; the distinction being that Cizhou ware is coated in a clear glaze while Cizhou-type ware is covered in a brown or black glaze. Robert Mowry has classified and excellently written on six categories of Cizhou-type ware: monochrome glazes, partridge feather glazes, oil-spot glazes, painted decoration, ribbed decoration, and cut-glaze decoration.[10]

Cizhou ware is thought to have influenced the designs found in Southeast Asia, particularly in Vietnam and Thailand.[11] However, though the style may have drifted, the majority of Cizhou wares were produced for the domestic market; it is uncommon to discover pieces outside of China though a few remains have been uncovered in Japan, Java, Celebes, and Sarawak.[12]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

He Li. Chinese Ceramics: A New Comprehensive Survey. NewYork: Rizzoli, 1996.

Liu Liang-yu. A Survey of Chinese Ceramics: Sung Wares. Taipei: Aries Gemini Publishing Ltd, 1991.

Mino, Yutaka. Freedom of Clay and Brush through Seven Centuries in Northern China: Tz’u’chou Type Wares, 960-1600 A.D. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980.

Mowry, Robert D. Hare’s Fur, Tortoiseshell, and Partridge Feathers: Chinese Brown- and Black-Glazed Ceramics, 400-1400. Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museum, 1996.

Vainker, S. J. Chinese Pottery and Porcelain from Prehistory to the Present. London: British Museum Press, 1991.

Wood, Nigel. Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation. London: A & C Black, 1999.

FOOTNOTES

1 Vainker, 117.

2 Mino, 9.

3 Lu Liang Yu, 132.

4 Vainker, 115.

5 Krahl, 261.

6 Liu Liang-yu, 136. Additionally, archeology shows that earlier pillows of the Song dynasty are fairly short and small, about 20-30 cm, while later pillows of the Yuan dynasty tend to be larger than 30 cm with some over 40cm long.

7 Nigel Wood, 129.

8 Krahl, 261.

9 Vainker, 117

10 Mowry, 31.

11 Liu Liang-yu, 132.

12 Mino, 10.

CELADON WARES

Celadon is a term used to describe several types of Chinese stoneware and porcelain, as well a ceramics from other countries, notably from Korea and Japan. The term is a vague one, applying to various types of green glazed ceramics, but not all ceramics with green glazes, there are several wares that have a green glaze that are not referred to as celadon. For example Green Jun and Ge Ware. For this reason there has been a move to try to clarify the situation by using the term ‘Green Ware’. But for now Celadon is a more familiar and therefore useful term.

The origins of the term Celadon are not clear, one theory is that the term first appeared in France in the 17th century and that it is named after the shepherd Celadon in Honoré d’Urfé’s French pastoral romance, L’Astrée (1627), who wore pale green ribbons. (D’Urfe, in turn, borrowed his character from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.) Another theory is that the term is a corruption of the name of Saladin, the Ayyubid Sultan, who in 1171 sent forty pieces of the ceramic to Nur ad-Din, Sultan of Syria. Yet a third theory is that the word derives from the Sanskrit sila and dhara, which mean “stone” and “green” respectively.